Skip to main contentBiographyFor aspiring artists coming of age in the 1950s, the domination of Abstract Expressionism was a challenge; they could choose to follow in the footsteps of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning and attempt their own variant on the style, or they could break away entirely. Some, like Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis, moved toward purified minimal statements, while others, such as Gregory Gillespie (1936–2000), gravitated toward a personalized form of realism. Gillespie’s detachment from the New York school was enhanced by the many years he spent abroad and, upon his return, his residence in Massachusetts.

Although the socioeconomic and psychological picture suggested by Gregory Joseph Gillespie’s upbringing may in future appear less overtly negative, the details of his childhood confirm the tremendous obstacles he overcame in becoming an acclaimed artist. He was born in Roselle Park, New Jersey, to an Irish-Catholic family of modest means. Later he reflected on how his early experiences impacted his work: “My childhood was quite unusual—an unusual blend of having a crazy mother (institutionalized for the rest of her life when I was five years old) and a severely alcoholic father. Added in was the influences of 1940s old-time ‘you are guilty and sinful and will burn in hell’-type Catholicism that was very scary to me as a child. I look around at the images I paint now and see Catholicism, insanity, chaos, weirdness. It’s natural for me to create these images. It’s almost as if, since there was so much chaos in my childhood, my job as an artist is to make it beautiful, to give it back some order and stability, and to make a living from it. So my job is to turn the chaos and pain into art.” [1] Gillespie’s father was superintendent of the East Jersey Railroad and after his mother’s institutionalization young Gregory lived with his paternal aunt and uncle.

Gillespie recalled how growing up, “I didn’t know what art was. The only art I knew anything about was comic books and Saturday Evening Post covers. In high school I was the only kid who could draw, and I became known as the class artist for my caricatures and pornographic cartoons.” [2] Because his family was poor, he was attracted to the tuition-free program at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Arts in New York. In 1954 Gillespie entered the night school program, intent on becoming a commercial artist, an idea he abandoned after a job doing paste-up in a commercial studio. Having been introduced to fine art through the school’s library, Gillespie became enamored with the highly detailed and illusionistic work of Italian early Renaissance artists such as Carlo Crivelli and Andrea Mantegna, as well as the emotional intensity of twentieth-century German expressionists, particularly Max Beckmann.

As an art student, Gillespie admired the Abstract Expressionists, but he was not inspired to paint like them. “I was probably the only kid at Cooper Union doing tight, figurative, narrative work. Everybody wanted me to loosen up and get with it. Even later, at the San Francisco Art Institute, they were trying to get me to pick up a big brush and be more spontaneous. I tried, but I always had this thing about content.” [3] In 1960 Gillespie left Cooper Union, which had only a three-year program, in order to complete his bachelor’s degree at the San Francisco Art Institute along with his wife and fellow artist, Frances Cohen, whom he had married the year before. Gillespie’s exposure to the California School of Abstract Expressionists through teachers such as Richard Diebenkorn and Elmer Bischoff did not significantly impact the style or subject of his work. After receiving his Master of Fine Arts degree in painting the next year, Gillespie won a Fulbright-Hays grant for study in Italy, specifically to study the early Renaissance artist Masaccio. The Fulbright grant was renewed for a second year followed by a Rosenthal Foundation grant, which sponsored travel throughout Europe and a stay in Spain. Three successive Chester Dale Fellowships funded Gillespie’s further study at the American Academy in Rome. He received a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation grant for painting in 1967.

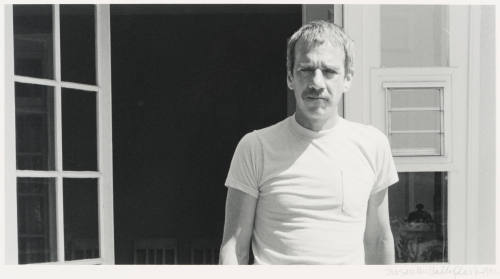

By 1970, when the Gillespies left Europe to return to the United States, Gregory had won an Italian painting prize, the Medaglia d’Oro del Senato della Repubblica, and had held a one-man exhibition at the American Academy in Rome in 1969. The artist was making a name for himself with his hyperrealistic, imaginative images that included portraits, self-portraits, mystical landscapes, and architectural interiors. His Trattoria images from the mid-sixties were inspired by the artist’s favorite eating places in Rome. His Self-Portrait in Black Shirt, 1968–1969, private collection, is an early example of a subject he painted frequently over his career. Gillespie scrutinized himself very closely, examining details created by his brushwork, by working under a magnifying glass. He was inspired by his subconscious thoughts and images to see beyond the surface level. When in 1999 an interviewer asked: “How do you seek that ‘beneath-the-surface’ reality? Did you meditate, take drugs, do hypnosis, or enlist outside aids to help in these quests?” Gillespie answered: “I did all of that, including self-hypnosis. That’s why I’ve never called myself a realist. … I like mixing things up—reality, imagination, paint, art, life, sculpture, painted sculpture. I’ve even painted my toilet and the walls around it, so that the entire bathroom has become like a walk-in sculpture.” [4] The viewer’s initial delight in the artist’s verisimilitude is put to the test by the unflinching presentation of Gillespie’s uncomfortable, piercing subject matter.

While still abroad, Gillespie had exhibited works in group exhibitions, including one at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In 1966 the Forum Gallery in New York hosted his first one-man exhibition; they continued to represent him throughout his career. Gillespie often expressed gratitude for the gallery’s constant support and in 1999 declared: “Forum has been great as far as consistent support through the lean times over the past forty years. This has given me the confidence and stability to explore at my own pace without feeling the pressures of the marketplace. It makes me feel so free. It’s just when there’s a cut-off date, a deadline, a show coming up, that all the fear comes in.” [5] One of his first collectors, in 1962, was Joseph Hirshhorn, and fifteen years later the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., organized the first retrospective of Gillespie’s work.

Living and working in Belchertown, Massachusetts, Gillespie stayed apart from the New York art scene; as art critic Roberta Smith commented, “he remained an art world outsider, respected by many but enthusiastically embraced by few.” [6] His second retrospective, twenty years after the first, was a touring exhibition organized by the Georgia Museum of Art, which travelled from April 1999 to March 2000. It was not shown in New York City, a terrible disappointment to Gillespie who confided in his journals that he longed for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. [7] In the exhibition catalogue, curator Donald Keyes closed his interview with Gillespie by asking about the sculptural tombs that the artist had been making. Gillespie responded, “I see them as a logical extension of the self-portraits combined with construction, assemblage, and shrine paintings,” adding, “I suppose I really want a museum to own it someday, with some of my ashes in an urn as part of it.” [8] Tragically, just a few weeks after the exhibition closed at the Butler Museum of Art in Youngstown, Ohio, Gregory Gillespie hung himself in his Belchertown studio. In hindsight, it is impossible not to see the artist’s vulnerability despite his considerable artistic achievement. In an otherwise upbeat article in Art News in 1986, Gillespie tellingly said: “I feel I’m not stable. I don’t have a strong sense of reality. I think I’ve developed a whole persona built on the fact that I make art: I go to the studio every day, that’s my identity. And, really, I want to be a great painter—not just ambitious, but great. Without it, I would face the void—which I don’t want to do.” [9]

Notes:

[1] Donald D. Keyes, “Interview with Gregory Gillespie,” in A Unique American Vision: Paintings by Gregory Gillespie, exhibition catalogue (Athens GA: Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, 1999), 54.

[2] Keyes, “Interview,” 49.

[3] Keyes, “Interview,” 50.

[4] Keyes, “Interview,” 51.

[5] Keyes, “Interview,” 54.

[6] Roberta Smith, “Gregory Gillespie, 64, An Unflinching Painter,” The New York Times April 29, 2000.

[7] Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., and Susan Ricci Stebbins, Life as Art: Paintings by Gregory Gillespie and Frances Cohen Gillespie, exhibition catalogue (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, 2003), 16.

[8] Keyes, “Interview,” 56.

[9] Gerrit Henry, “Gregory Gillespie’s Manic Masterpieces,” Art News (December 1986), 120.

Gregory Gillespie

1936 - 2000

Although the socioeconomic and psychological picture suggested by Gregory Joseph Gillespie’s upbringing may in future appear less overtly negative, the details of his childhood confirm the tremendous obstacles he overcame in becoming an acclaimed artist. He was born in Roselle Park, New Jersey, to an Irish-Catholic family of modest means. Later he reflected on how his early experiences impacted his work: “My childhood was quite unusual—an unusual blend of having a crazy mother (institutionalized for the rest of her life when I was five years old) and a severely alcoholic father. Added in was the influences of 1940s old-time ‘you are guilty and sinful and will burn in hell’-type Catholicism that was very scary to me as a child. I look around at the images I paint now and see Catholicism, insanity, chaos, weirdness. It’s natural for me to create these images. It’s almost as if, since there was so much chaos in my childhood, my job as an artist is to make it beautiful, to give it back some order and stability, and to make a living from it. So my job is to turn the chaos and pain into art.” [1] Gillespie’s father was superintendent of the East Jersey Railroad and after his mother’s institutionalization young Gregory lived with his paternal aunt and uncle.

Gillespie recalled how growing up, “I didn’t know what art was. The only art I knew anything about was comic books and Saturday Evening Post covers. In high school I was the only kid who could draw, and I became known as the class artist for my caricatures and pornographic cartoons.” [2] Because his family was poor, he was attracted to the tuition-free program at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Arts in New York. In 1954 Gillespie entered the night school program, intent on becoming a commercial artist, an idea he abandoned after a job doing paste-up in a commercial studio. Having been introduced to fine art through the school’s library, Gillespie became enamored with the highly detailed and illusionistic work of Italian early Renaissance artists such as Carlo Crivelli and Andrea Mantegna, as well as the emotional intensity of twentieth-century German expressionists, particularly Max Beckmann.

As an art student, Gillespie admired the Abstract Expressionists, but he was not inspired to paint like them. “I was probably the only kid at Cooper Union doing tight, figurative, narrative work. Everybody wanted me to loosen up and get with it. Even later, at the San Francisco Art Institute, they were trying to get me to pick up a big brush and be more spontaneous. I tried, but I always had this thing about content.” [3] In 1960 Gillespie left Cooper Union, which had only a three-year program, in order to complete his bachelor’s degree at the San Francisco Art Institute along with his wife and fellow artist, Frances Cohen, whom he had married the year before. Gillespie’s exposure to the California School of Abstract Expressionists through teachers such as Richard Diebenkorn and Elmer Bischoff did not significantly impact the style or subject of his work. After receiving his Master of Fine Arts degree in painting the next year, Gillespie won a Fulbright-Hays grant for study in Italy, specifically to study the early Renaissance artist Masaccio. The Fulbright grant was renewed for a second year followed by a Rosenthal Foundation grant, which sponsored travel throughout Europe and a stay in Spain. Three successive Chester Dale Fellowships funded Gillespie’s further study at the American Academy in Rome. He received a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation grant for painting in 1967.

By 1970, when the Gillespies left Europe to return to the United States, Gregory had won an Italian painting prize, the Medaglia d’Oro del Senato della Repubblica, and had held a one-man exhibition at the American Academy in Rome in 1969. The artist was making a name for himself with his hyperrealistic, imaginative images that included portraits, self-portraits, mystical landscapes, and architectural interiors. His Trattoria images from the mid-sixties were inspired by the artist’s favorite eating places in Rome. His Self-Portrait in Black Shirt, 1968–1969, private collection, is an early example of a subject he painted frequently over his career. Gillespie scrutinized himself very closely, examining details created by his brushwork, by working under a magnifying glass. He was inspired by his subconscious thoughts and images to see beyond the surface level. When in 1999 an interviewer asked: “How do you seek that ‘beneath-the-surface’ reality? Did you meditate, take drugs, do hypnosis, or enlist outside aids to help in these quests?” Gillespie answered: “I did all of that, including self-hypnosis. That’s why I’ve never called myself a realist. … I like mixing things up—reality, imagination, paint, art, life, sculpture, painted sculpture. I’ve even painted my toilet and the walls around it, so that the entire bathroom has become like a walk-in sculpture.” [4] The viewer’s initial delight in the artist’s verisimilitude is put to the test by the unflinching presentation of Gillespie’s uncomfortable, piercing subject matter.

While still abroad, Gillespie had exhibited works in group exhibitions, including one at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In 1966 the Forum Gallery in New York hosted his first one-man exhibition; they continued to represent him throughout his career. Gillespie often expressed gratitude for the gallery’s constant support and in 1999 declared: “Forum has been great as far as consistent support through the lean times over the past forty years. This has given me the confidence and stability to explore at my own pace without feeling the pressures of the marketplace. It makes me feel so free. It’s just when there’s a cut-off date, a deadline, a show coming up, that all the fear comes in.” [5] One of his first collectors, in 1962, was Joseph Hirshhorn, and fifteen years later the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., organized the first retrospective of Gillespie’s work.

Living and working in Belchertown, Massachusetts, Gillespie stayed apart from the New York art scene; as art critic Roberta Smith commented, “he remained an art world outsider, respected by many but enthusiastically embraced by few.” [6] His second retrospective, twenty years after the first, was a touring exhibition organized by the Georgia Museum of Art, which travelled from April 1999 to March 2000. It was not shown in New York City, a terrible disappointment to Gillespie who confided in his journals that he longed for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. [7] In the exhibition catalogue, curator Donald Keyes closed his interview with Gillespie by asking about the sculptural tombs that the artist had been making. Gillespie responded, “I see them as a logical extension of the self-portraits combined with construction, assemblage, and shrine paintings,” adding, “I suppose I really want a museum to own it someday, with some of my ashes in an urn as part of it.” [8] Tragically, just a few weeks after the exhibition closed at the Butler Museum of Art in Youngstown, Ohio, Gregory Gillespie hung himself in his Belchertown studio. In hindsight, it is impossible not to see the artist’s vulnerability despite his considerable artistic achievement. In an otherwise upbeat article in Art News in 1986, Gillespie tellingly said: “I feel I’m not stable. I don’t have a strong sense of reality. I think I’ve developed a whole persona built on the fact that I make art: I go to the studio every day, that’s my identity. And, really, I want to be a great painter—not just ambitious, but great. Without it, I would face the void—which I don’t want to do.” [9]

Notes:

[1] Donald D. Keyes, “Interview with Gregory Gillespie,” in A Unique American Vision: Paintings by Gregory Gillespie, exhibition catalogue (Athens GA: Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, 1999), 54.

[2] Keyes, “Interview,” 49.

[3] Keyes, “Interview,” 50.

[4] Keyes, “Interview,” 51.

[5] Keyes, “Interview,” 54.

[6] Roberta Smith, “Gregory Gillespie, 64, An Unflinching Painter,” The New York Times April 29, 2000.

[7] Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., and Susan Ricci Stebbins, Life as Art: Paintings by Gregory Gillespie and Frances Cohen Gillespie, exhibition catalogue (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, 2003), 16.

[8] Keyes, “Interview,” 56.

[9] Gerrit Henry, “Gregory Gillespie’s Manic Masterpieces,” Art News (December 1986), 120.

Person TypeIndividual