Edward Ruscha

It should not surprise anyone that southern California was the first place in the country to recognize the emerging Pop Art movement. Known for the Beach Boys, Sunset Boulevard, and Hollywood, the area espoused popular culture. At the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in 1962, Andy Warhol received recognition for the first major exhibition of his Campbell Soup cans. That same year, the Pasadena Art Museum mounted New Paintings of Common Objects, which included work by Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and a local painter, Edward Ruscha. In an interview, he sardonically commented on the perennial competition between the coasts: “For an artist, L.A. promises nothing and delivers not much more. Whereas New York promises everything for an artist and delivers zilch.” [1]

Ruscha, who is known as “Ed,” was born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1937 but grew up in Oklahoma City. As a child he showed a precocious interest in art and was particularly fond of drawing cartoons. In high school, he discovered, through reproductions, the work of the great Dadaist Marcel Duchamp, which greatly influenced his own development as an artist. In 1956, he began his studies at the Chouinard Art Institute, now the California Institute of the Arts, and graduated four years later. His courses emphasized commercial design and fine arts, and he supported himself as a layout artist while at school and afterward. The planning and concentration that graphic design requires contrasted with the intuitive approach of his art school instructors, who operated under the onus of Abstract Expressionism.

In 1961, Ruscha, who calls himself “a painter who takes photographs,” traveled for over six months throughout Europe, taking black and white snapshots of ordinary street scenes. Many of these became source material for his paintings and artist’s books. Between 1963 and 1978 he self-published sixteen books in small editions of about one thousand. His first endeavor, Twenty-Six Gas Stations, derived from his many trips on Route 66 between Los Angeles and Oklahoma City; it addresses the American obsession with the automobile and the open road. Two later projects, Some Los Angeles Apartments and Every Building on the Sunset Strip, reflect his impressions of his adopted home. For him, “My statements about this place called Los Angeles are never self-consciously attendant on the idea of making it specifically a commentary upon Los Angeles. My imagery can come from anywhere in America—it’s American. … My work has less to say specifically about this city of Los Angeles, but it’s the city that gave all my inspiration to me.” [2]

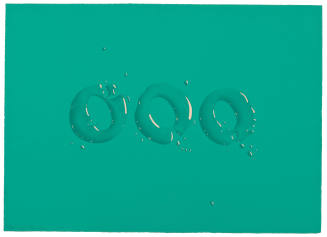

In addition to Duchamp, the artists who exerted the greatest influence on Ruscha were Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, whose work he first encountered in magazines. Ruscha commented on the attraction: “The work of Johns and Rauschenberg marked a departure in the sense that their work was premeditated, and Abstract Expressionism was not. … So when I saw the target [by Johns], I was especially taken with the fact that it was symmetrical, which was just absolutely taboo in art school—you didn’t make anything symmetrical.” In addition, both artists incorporated words in their work, a motif that dominated Ruscha’s output well into the 1970s and aligned him with other Pop artists. At first, he employed single words, usually placed centrally against a backdrop that gives the impression of vast space. He believed that, “if you look at a word long enough, it begins to lose its meaning.” [3] Gradually he experimented with different materials, including various kinds of liquids, and also fabrics, such as silk and taffeta, for supports. In 1971, after a two-year hiatus when he did not paint but made books, prints, and films, he began to construct images with phrases and short sentences. For these he invented his own typography—a simple, unassuming system of lettering that he dubbed “Boy Scout Utility Modern.”

In the mid-1980s, he began to airbrush his paintings, creating slicker surfaces. For subject matter, he turned to landscape, often mountainous scenes that resemble travel posters or calendars. He continued to overlay words and phrases, sometimes with a mocking bent: “The End,” “Exit,” or questions: “Not a Bad World is It?” He developed a penchant for substituting blank rectangles where words might appear, leaving the viewer to fill in the voids. In the 1990s, a favored motif was a low-profile industrial building rendered against an ominous sky with labels such as “Tech-Chem,” or “Fat Boy.” This body of work, called Course of Empire in emulation of Thomas Cole, was exhibited in the American pavilion at the 2005 Venice Biennale. He was also awarded several prestigious commissions, including a large-scale mural for the Denver Public Library designed by Michael Graves, and another for the new J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. In 2010, Ruscha issued a two-hundred-plus-page book that combined his artwork with Jack Kerouac’s epic, On the Road.

Despite his affiliation with the Pop Art movement and his preoccupation with banal imagery, Ruscha maintains that in truth he is an abstractionist: “When I began painting, all my paintings were of words which were guttural utterances like ‘smash,’ ‘boss,’ ‘eat.’ I didn’t see that as literature, because it didn’t complete thoughts. … The words have these abstract shapes, they live in a world of no size. You can make them any size, and what’s the real size? Nobody knows…” [4]

Notes:

[1] Ruscha, interview with Paul Karlstorm, “Interview with Edward Ruscha in his Western Avenue Studio,” 1980–1981, California Oral History Project, Archives of American Art, quoted in Richard D. Marshall, Ed Ruscha (New York and London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2003), 12.

[2] Ruscha, interview with Karlstorm, quoted in Marshall, Ed Ruscha, 180.

[3] Ruscha, interview with Karlstorm, quoted in Marshall, Ed Ruscha, 9, and Ruscha, quoted in Howardena Pindell, “Words with Ed Ruscha,” in Alexandra Schwartz, ed. Ed Ruscha: Leave Any Information at the Signal. Writings, Interviews, Bits, Pages (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 248.

[4] Ruscha quoted in Fred Fehlau, “Ed Ruscha,” Flash Art (January/February 1988), 70, quoted in Marshall, Ed Ruscha, 106.