Skip to main contentBiographyIn the early years of the twentieth century, the interaction of American and European modernists was nurtured by several phenomena: the salons hosted by Gertrude and Leo Stein in Paris; Alfred Stieglitz’s small gallery on Fifth Avenue, known as 291; and the famed Armory Show. At the Steins’ apartment at 27 Rue de Fleurus, many Americans had their first encounter with the revolutionary work of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. In New York, Stieglitz sponsored modernist exhibitions by artists from both sides of the Atlantic: Auguste Rodin, John Marin, Paul Cézanne, and Marsden Hartley. The 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art—better known as the Armory Show—became a watershed event that brought critical acclaim and public outrage. Among the artists who participated in all of these were Alfred Maurer, Max Weber, and the slightly eccentric Abraham Walkowitz (1878–1965).

A native of Tyumen, Siberia, Walkowitz immigrated to the United States around age nine, but before that he had revealed a precocious interest in art. In an interview for the Archives of American Art, he recalled, “When I was a kid, about five years old, I used to draw with chalk, all over the floors and everything. … I suppose it’s in me. I remember myself as a little boy of three or four, taking chalk and made drawings. I suppose I just had to become an artist.” [1] In New York, he sketched his Jewish neighbors, worked as a sign painter, and, from 1900 to 1906, taught at the Educational Alliance, a settlement house for recent immigrants. He studied under Walter Shirlaw at the Art Students League and at the National Academy of Design. In 1906, with funds from friends, Walkowitz went to Paris where he attended the Académie Julian, witnessed the memorial exhibition of Cézanne, and frequented museums. A turning point came when he met Isadora Duncan in Rodin’s studio and shortly afterward observed her avant-garde dancing style at a private salon. This encounter led to a near-obsessive interest in drawing and painting the dancer; over his lifetime, Walkowitz portrayed her approximately five thousand times.

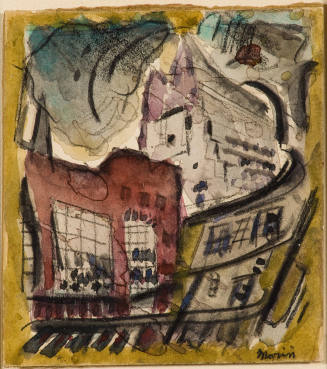

Upon his return to New York, Walkowitz supported himself with commercial assignments and had an exhibition at a frame shop on Madison Avenue, which he claimed was the first showing of modern art in this country. He later recalled how the press “roasted him.” [2] Hartley introduced him to Stiegltiz, who mounted four exhibitions of Walkowitz’s work between 1911 and 1916. The gallerist and the artist worked together on hanging shows and shared a vision for modernism in America. As the latter explained: “I do not avoid objectivity or seek subjectivity but try to find an equivalent for whatever is the effect of my relation to a thing. I am seeking to attune my art to what I feel to be the keynote of an experience. … I try to record the sensation in visual forms, in the medium of line and space divided. When the line and color are sensitized, they seem to me alive with the rhythm which I felt in the thing that stimulated my imagination.” [3]

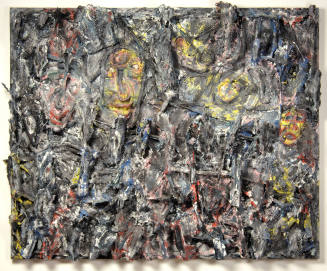

In the Armory Show, Walkowitz was represented by five oils, five drawings, one watercolor, and one color monotype. Several of the oils were Italian scenes, the result of a trip there in 1907. The works on paper were all untitled, and may have included depictions of Duncan. In addition to his portrayals of the famous dancer, Walkowitz depicted other figurative subjects—picnics, promenades, idyllic scenes of nude bathers, and a few landscapes. During World War II, a series of his drawings railed against the atrocities of war and showed lame and crippled victims of Hitler and Fascism. For over twenty years, he was active with the Society of Independent Artists, a group that sponsored non-juried shows and hung work according to the alphabet.

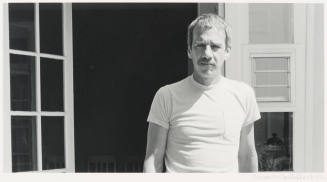

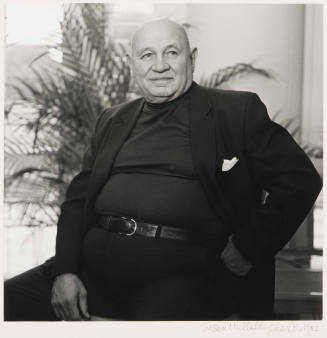

Although respected by fellow artists, who called him “Walky,” success and fame did not come his way, and by the mid-1940s he had all but abandoned making art due to failing eyesight. Believing that all artists portray themselves not their sitters, Walkowitz persuaded one hundred painters and sculptors to render his portrait. The results formed an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum which was featured in Life magazine. Calling himself an “idiot” because of the time and expense involved in the yearlong project, he wrote in the catalogue’s preface: “This exhibition is the presentation of an experiment; the relationship between the artists and the object he sees is complicated and little understood. The experiment, 100 artists and one subject. Each artist was completely free to choose his medium, his interpretation, and form. The results vary with the personality of the artist. If proof were necessary that no two persons see an object alike, this is proof indeed. But what is more important, here one discovers that no matter what or whom they paint, artists always reveal themselves. The exhibition offers a unique opportunity for study to laymen, art students, artists and psychologists.” [4] As the fiftieth anniversary of the Armory Show rolled around in 1963, Walkowitz, virtually blind, was honored by the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Notes:

[1] Walkowitz interview, Abram Lerner, and Mary Bartlett Cowdrey, “Oral History Interview With Abraham Walkowitz,” December 8 and 22, 1958, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/oralhistories/transcripts/walkow58.htm

[2] Walkowitz interview, Archives of American Art.

[3] Walkowitz quoted in Martica Sawin, “Abraham Walkowtiz,” Arts Magazine, March 1964, 46.

[4] “One Hundred Artists and Walkowitz,” exhibition press release, February 8, 1944, Brooklyn Museum Archives, http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/exhibitions

Abraham Walkowitz

1880 - 1965

A native of Tyumen, Siberia, Walkowitz immigrated to the United States around age nine, but before that he had revealed a precocious interest in art. In an interview for the Archives of American Art, he recalled, “When I was a kid, about five years old, I used to draw with chalk, all over the floors and everything. … I suppose it’s in me. I remember myself as a little boy of three or four, taking chalk and made drawings. I suppose I just had to become an artist.” [1] In New York, he sketched his Jewish neighbors, worked as a sign painter, and, from 1900 to 1906, taught at the Educational Alliance, a settlement house for recent immigrants. He studied under Walter Shirlaw at the Art Students League and at the National Academy of Design. In 1906, with funds from friends, Walkowitz went to Paris where he attended the Académie Julian, witnessed the memorial exhibition of Cézanne, and frequented museums. A turning point came when he met Isadora Duncan in Rodin’s studio and shortly afterward observed her avant-garde dancing style at a private salon. This encounter led to a near-obsessive interest in drawing and painting the dancer; over his lifetime, Walkowitz portrayed her approximately five thousand times.

Upon his return to New York, Walkowitz supported himself with commercial assignments and had an exhibition at a frame shop on Madison Avenue, which he claimed was the first showing of modern art in this country. He later recalled how the press “roasted him.” [2] Hartley introduced him to Stiegltiz, who mounted four exhibitions of Walkowitz’s work between 1911 and 1916. The gallerist and the artist worked together on hanging shows and shared a vision for modernism in America. As the latter explained: “I do not avoid objectivity or seek subjectivity but try to find an equivalent for whatever is the effect of my relation to a thing. I am seeking to attune my art to what I feel to be the keynote of an experience. … I try to record the sensation in visual forms, in the medium of line and space divided. When the line and color are sensitized, they seem to me alive with the rhythm which I felt in the thing that stimulated my imagination.” [3]

In the Armory Show, Walkowitz was represented by five oils, five drawings, one watercolor, and one color monotype. Several of the oils were Italian scenes, the result of a trip there in 1907. The works on paper were all untitled, and may have included depictions of Duncan. In addition to his portrayals of the famous dancer, Walkowitz depicted other figurative subjects—picnics, promenades, idyllic scenes of nude bathers, and a few landscapes. During World War II, a series of his drawings railed against the atrocities of war and showed lame and crippled victims of Hitler and Fascism. For over twenty years, he was active with the Society of Independent Artists, a group that sponsored non-juried shows and hung work according to the alphabet.

Although respected by fellow artists, who called him “Walky,” success and fame did not come his way, and by the mid-1940s he had all but abandoned making art due to failing eyesight. Believing that all artists portray themselves not their sitters, Walkowitz persuaded one hundred painters and sculptors to render his portrait. The results formed an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum which was featured in Life magazine. Calling himself an “idiot” because of the time and expense involved in the yearlong project, he wrote in the catalogue’s preface: “This exhibition is the presentation of an experiment; the relationship between the artists and the object he sees is complicated and little understood. The experiment, 100 artists and one subject. Each artist was completely free to choose his medium, his interpretation, and form. The results vary with the personality of the artist. If proof were necessary that no two persons see an object alike, this is proof indeed. But what is more important, here one discovers that no matter what or whom they paint, artists always reveal themselves. The exhibition offers a unique opportunity for study to laymen, art students, artists and psychologists.” [4] As the fiftieth anniversary of the Armory Show rolled around in 1963, Walkowitz, virtually blind, was honored by the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Notes:

[1] Walkowitz interview, Abram Lerner, and Mary Bartlett Cowdrey, “Oral History Interview With Abraham Walkowitz,” December 8 and 22, 1958, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/oralhistories/transcripts/walkow58.htm

[2] Walkowitz interview, Archives of American Art.

[3] Walkowitz quoted in Martica Sawin, “Abraham Walkowtiz,” Arts Magazine, March 1964, 46.

[4] “One Hundred Artists and Walkowitz,” exhibition press release, February 8, 1944, Brooklyn Museum Archives, http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/exhibitions

Person TypeIndividual