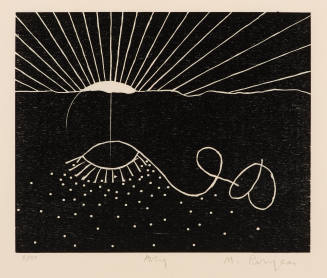

Skip to main contentBiographySculptor Louise Nevelson (1899–1988) described her artistic goals in this way: “My total conscious search in life has been for a new seeing, a new image, a new insight. This search not only includes the object, but the in-between places, the dawns and dusks, the objective world, the heavenly spheres, the places between the land and the sea.” [1] This statement captures not only her strikingly personal iconography—often centered around celestial or earthly bodies or phenomena such as moons, night, dusk, dawn, tides, skies, rain, light, wind, shadows, and stars—but her interest in structure as well—in exploring, in her large-scale wooden assemblage pieces, the “in-between places.”

Although Nevelson expressed an interest in visual art from childhood on, it took decades for the artist to develop her distinctive style and to find recognition in the art world. She was born Leah Berliawsky in Kiev, Ukraine. Her father immigrated to America first, settling in Rockland, Maine, and then sending for his family. He eventually achieved modest success in the timber business; consequently, his daughter grew up keenly attuned to the possibilities of wood and construction. Although she felt isolated as a Jewish girl growing up in a town with few Jewish families, young Leah distinguished herself by excelling at music and art. She also demonstrated a penchant for arranging furniture, an interest that indicates a heightened spatial awareness from an early age. She later changed her name to the more American-sounding Louise.

At the age of twenty-one, she married Charles Nevelson, part of a well-off shipping family from New York. She moved with her husband to New York City; their son was born in 1922. Over the next few years, Nevelson availed herself of classes in painting, drawing, theater, and dance. In 1929, she began studying with Kenneth Hayes Miller at the Art Students League. She was strongly attracted to Cubism, and in 1931 left her son with relatives in Maine and traveled to Germany to study with Hans Hofmann. She never returned to her marriage; instead, she drifted around Europe, studying briefly with Hofmann and then working for a time as an extra in films. Upon her return to New York in 1932, Nevelson studied again with Hofmann, who had taken a post at the Art Students League. She also worked as an assistant for the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. Through Rivera, Nevelson was exposed for the first time to Pre-Columbian art, and she was drawn both to Mayan iconography and to the totemic structures she encountered. Her work at the time centered around blocky sculptural figures reminiscent of Pablo Picasso.

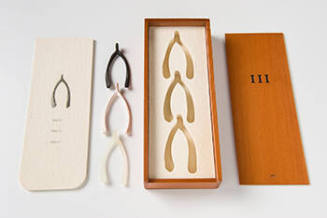

In the 1930s, Nevelson worked for the Work Progress Administration and participated in group shows at Manhattan galleries. An exhibition in 1936 at the ACA gallery drew attention from the The New York Times, but she had little success selling her work in the male-dominated environment of the mid-twentieth-century art world. [2] In 1941, she had her first one-woman show at Nierendorf Gallery. It was at about this time that Nevelson began using found objects to create her wooden assemblage pieces. Driven in part by dire financial circumstances, Nevelson had gathered wood to burn in the fireplace. Nevelson later recalled, “I had all this wood lying around and I began to move it around, I began to compose. Anywhere I found wood, I took it home and started working with it. It might be on the streets, it might be from furniture factories. Friends might bring me wood.” [3] Nevelson often used familiar shapes in her work: finials, chair rails, architectural molding, and furniture legs.

Nevelson’s breakthrough came in the mid-1950s when she decided to unify her assemblage sculptures by painting them entirely black. At about the same time, she stumbled upon the idea of using the crates that served as pedestals for her sculptures in a gallery show as boxes in which to place her found objects and then to paint the entire structure with flat black paint. The result resembles a shadow box full of contrasting forms and lines. Gradually, Nevelson increased the scale of these pieces, creating entire walls and artistic environments composed of crate-like component parts. The artist presented this new work at the Grand Central Moderns Gallery in 1958 in an exhibition called Moon Garden Plus One. Hilton Kramer, critic for The New York Times, wrote that the sculptures were “appalling and marvelous, utterly shocking in the way they violate our received ideas on the subject of sculpture and the confusion of genres, yet profoundly exhilarating in the way they open an entire realm of possibility.” [4] The exhibition attracted the attention of Dorothy Miller from the Museum of Modern Art, who invited Nevelson to participate in a group show at the museum. For that exhibition in 1959, the artist presented a piece in all white called Dawn’s Wedding Feast. Eventually, she expanded her palette to include pieces painted all gold as well as black or white. She also experimented with Plexiglas as a material.

Thereafter, success came quickly. She acquired gallery representation, first with the Martha Jackson Gallery and then in 1964 with the Pace Gallery, who represented her for the rest of her life. She achieved financial security through sales of her sculptures as well as through the production of marketable work such as prints and multiples. She represented the United States at the 1962 Venice Biennale and developed an iconic personal style of dress, favoring dramatic clothing and dark eye makeup. When she began experimenting with large-scale steel sculptures in the 1960s, she received commissions for such pieces from prestigious universities and government organizations. For St. Peter’s Church in New York City, she installed one of her all-encompassing environments in the Chapel of the Good Shepherd. The Whitney Museum of American Art mounted the first retrospective of her work in 1967 and another in 1980. She received the National Medal of the Arts from President Reagan in 1985. Upon her death three years later, Nevelson was recognized as one of the most significant sculptors of the twentieth century.

Notes:

[1] Nevelson, quoted in Donna Seaman, “The Empress of In-Between: A Portrait of Louise Nevelson,” Triquarterly 132 (2008), 9.

[2] John Russell, “Louise Nevelson, Artist Renowned for Wall Sculptures, Is Dead at 88.” The New York Times (April 18, 1988), Section A, Page 1, Column 5. http://www.nytimes.com/1988/04/18/obituaries/louise-nevelson-artist-renowned-for-wall-sculptures-is-dead-at-88.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

[3] Seaman, “The Empress of In-Between,” 12, and Nevelson quoted in Louise Nevelson, Dawns and Dusks: Taped Conversations with Diana Mackown (New York: Scribner, 1976), 76.

[4] Russell, Section A, Page 1, Column 5.

Louise Nevelson

1899 - 1988

Although Nevelson expressed an interest in visual art from childhood on, it took decades for the artist to develop her distinctive style and to find recognition in the art world. She was born Leah Berliawsky in Kiev, Ukraine. Her father immigrated to America first, settling in Rockland, Maine, and then sending for his family. He eventually achieved modest success in the timber business; consequently, his daughter grew up keenly attuned to the possibilities of wood and construction. Although she felt isolated as a Jewish girl growing up in a town with few Jewish families, young Leah distinguished herself by excelling at music and art. She also demonstrated a penchant for arranging furniture, an interest that indicates a heightened spatial awareness from an early age. She later changed her name to the more American-sounding Louise.

At the age of twenty-one, she married Charles Nevelson, part of a well-off shipping family from New York. She moved with her husband to New York City; their son was born in 1922. Over the next few years, Nevelson availed herself of classes in painting, drawing, theater, and dance. In 1929, she began studying with Kenneth Hayes Miller at the Art Students League. She was strongly attracted to Cubism, and in 1931 left her son with relatives in Maine and traveled to Germany to study with Hans Hofmann. She never returned to her marriage; instead, she drifted around Europe, studying briefly with Hofmann and then working for a time as an extra in films. Upon her return to New York in 1932, Nevelson studied again with Hofmann, who had taken a post at the Art Students League. She also worked as an assistant for the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. Through Rivera, Nevelson was exposed for the first time to Pre-Columbian art, and she was drawn both to Mayan iconography and to the totemic structures she encountered. Her work at the time centered around blocky sculptural figures reminiscent of Pablo Picasso.

In the 1930s, Nevelson worked for the Work Progress Administration and participated in group shows at Manhattan galleries. An exhibition in 1936 at the ACA gallery drew attention from the The New York Times, but she had little success selling her work in the male-dominated environment of the mid-twentieth-century art world. [2] In 1941, she had her first one-woman show at Nierendorf Gallery. It was at about this time that Nevelson began using found objects to create her wooden assemblage pieces. Driven in part by dire financial circumstances, Nevelson had gathered wood to burn in the fireplace. Nevelson later recalled, “I had all this wood lying around and I began to move it around, I began to compose. Anywhere I found wood, I took it home and started working with it. It might be on the streets, it might be from furniture factories. Friends might bring me wood.” [3] Nevelson often used familiar shapes in her work: finials, chair rails, architectural molding, and furniture legs.

Nevelson’s breakthrough came in the mid-1950s when she decided to unify her assemblage sculptures by painting them entirely black. At about the same time, she stumbled upon the idea of using the crates that served as pedestals for her sculptures in a gallery show as boxes in which to place her found objects and then to paint the entire structure with flat black paint. The result resembles a shadow box full of contrasting forms and lines. Gradually, Nevelson increased the scale of these pieces, creating entire walls and artistic environments composed of crate-like component parts. The artist presented this new work at the Grand Central Moderns Gallery in 1958 in an exhibition called Moon Garden Plus One. Hilton Kramer, critic for The New York Times, wrote that the sculptures were “appalling and marvelous, utterly shocking in the way they violate our received ideas on the subject of sculpture and the confusion of genres, yet profoundly exhilarating in the way they open an entire realm of possibility.” [4] The exhibition attracted the attention of Dorothy Miller from the Museum of Modern Art, who invited Nevelson to participate in a group show at the museum. For that exhibition in 1959, the artist presented a piece in all white called Dawn’s Wedding Feast. Eventually, she expanded her palette to include pieces painted all gold as well as black or white. She also experimented with Plexiglas as a material.

Thereafter, success came quickly. She acquired gallery representation, first with the Martha Jackson Gallery and then in 1964 with the Pace Gallery, who represented her for the rest of her life. She achieved financial security through sales of her sculptures as well as through the production of marketable work such as prints and multiples. She represented the United States at the 1962 Venice Biennale and developed an iconic personal style of dress, favoring dramatic clothing and dark eye makeup. When she began experimenting with large-scale steel sculptures in the 1960s, she received commissions for such pieces from prestigious universities and government organizations. For St. Peter’s Church in New York City, she installed one of her all-encompassing environments in the Chapel of the Good Shepherd. The Whitney Museum of American Art mounted the first retrospective of her work in 1967 and another in 1980. She received the National Medal of the Arts from President Reagan in 1985. Upon her death three years later, Nevelson was recognized as one of the most significant sculptors of the twentieth century.

Notes:

[1] Nevelson, quoted in Donna Seaman, “The Empress of In-Between: A Portrait of Louise Nevelson,” Triquarterly 132 (2008), 9.

[2] John Russell, “Louise Nevelson, Artist Renowned for Wall Sculptures, Is Dead at 88.” The New York Times (April 18, 1988), Section A, Page 1, Column 5. http://www.nytimes.com/1988/04/18/obituaries/louise-nevelson-artist-renowned-for-wall-sculptures-is-dead-at-88.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

[3] Seaman, “The Empress of In-Between,” 12, and Nevelson quoted in Louise Nevelson, Dawns and Dusks: Taped Conversations with Diana Mackown (New York: Scribner, 1976), 76.

[4] Russell, Section A, Page 1, Column 5.

Person TypeIndividual