Mary Frank

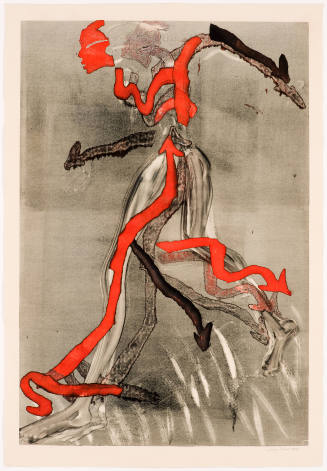

The 1970s witnessed a surge of women artists gaining recognition within an art world that had become greatly diversified in style, subject, and materials. The art of Mary Frank (born 1933) resists easy categorization and, at first glance, seems outside the mainstream of late twentieth century art. Her choice of hand-built clay as her medium for fine art sculpture and her exploration of the interconnectedness of the natural world and humanity through the imagery of the body set her apart. Art collector and scholar Barbara Millhouse recalled that in the late 1970s Frank had an important exhibition, which “seemed to rank her among the most creative women artists of the times. People who entered the exhibition were gasping with awe.” [1] Since then her visibility has waned, but that can be attributed in part to her disregard of the contemporary art scene in pursuit of her own aesthetic interests, consistent over more than five decades of artistic production. Frank addresses issues of the body, social justice, and the environment—concerns she shares with other women artists such as Marina Abramovic and Ana Mendieta. Frank’s works have always been figurative, as curator Paul Master-Karnik explains: “[at] the core of Mary Frank’s art is the human figure represented in various stages of self-actualization, becoming progressively aware of an intimate and organic relation with the natural world.” [2]

The only child of American painter Eleanore Lockspeiser and musicologist and composer Edward Lockspeiser, Mary was born in London on the eve of World War II. Her parents were non-observant Jews. Like other English children, she was evacuated from London to the countryside during the Blitz, until she and her mother left Europe to join her maternal grandparents in New York. They lived first in Brooklyn, but then moved to a small place in Greenwich Village. Mary always had access to art supplies, art books, and music lessons—she sang and played a recorder, she carved wood, and she made various things. She attended the High School for Music and Art but, in 1949, transferred to the Professional Children’s School in order to study dance under Martha Graham, who became an important influence on Mary beyond her groundbreaking choreography in modern dance. The artist later recalled, “She talked about Greek ideas I wasn’t interested in at the time, and she talked about sculpture. Particularly Henry Moore, the first sculptor I felt connected to.” [3]

At seventeen Mary ended her formal study of dance. She had met and fallen in love with the photographer Robert Frank, who had emigrated from Switzerland in 1947. The summer before her senior year in high school Mary traveled to Paris to see her father, who had never reunited with the family; her parents divorced after the war ended. In an almost unreal sequence of events, Mr. Lockspeiser—misunderstanding his daughter and feeling that Mary should be separated from Robert, who had followed her—had her institutionalized in a French hospital. Mary remembers seeing a beautiful walled garden at the hospital before being placed in solitary confinement. It was two weeks before her mother came to have her discharged. Mary and Robert Frank married after her graduation from high school in 1950 and she spent the 1950s caring for two children while also studying drawing with Max Beckman and Hans Hofmann. Robert Frank received a two-year Guggenheim grant to photograph across the country; the family joined him in 1955 and travelled through the Southwest. The result was Robert Frank’s acclaimed photo-essay, The Americans. Although her husband was a prominent member of the New York art scene, Mary Frank pursued her own interests, initially woodcarving then working with plaster, wood, and wax. She began making monoprints in 1967 and also did illustrations for children’s books. By 1969, the Franks divorced; she was teaching drawing and sculpture at the Graduate School, Queens College, and had begun creating sculpture in clay.

Clay as sculpture rather than object was both innovative and ancient as Frank practiced it. Her lifelong fascination with ancient civilizations—a remembered image from childhood of a photograph of a small doll’s head from India in Verve magazine; awareness of the human figure informed by her dance studies; discoveries such as the terra cotta warriors of China in 1974—all informed her practice as she investigated endless possibilities in clay. Her first works combined landscape elements such as dunes, waves, and rocks with small figures or parts of figures in shifting scales. Her series included heads, figurative sundials, two-part pieces that had heads juxtaposed with animals or plants, and vertical sculptures of women in motion. Frank acquired a summer home in Lake Hills, New York, in 1973 and built her first kiln there. She started to work on a larger scale, creating more life-size figures from small parts that had been fired separately. These recumbent figures were mostly female and, in the words of art historian Hayden Herrera, “the sculptor performs her own kind of genesis: clay becomes flesh, a body becomes landscape, landscape becomes clay. The recumbent nudes are images of multiple fertility: female, artistic, and terrestrial.” [4]

In the midst of this incredibly productive period, Frank’s daughter Andrea died in a plane crash in Guatemala in late 1974. “At once, even if only to a knowledgeable audience, figures that until that moment had been readable as metaphors took on a fearful reality. The cross-over between ecstasy and anguish, that ancient theme of tragic drama, became the new theme.” [5] The following year Frank’s mother developed cancer and her son Pablo was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease. Though both would live for several more years, Frank was nearly overwhelmed by grief. She survived by immersing herself in her home and garden in the Catskills and continuing to make art. In the following decade she travelled to Greece, France, Morocco, Japan, and Israel, explored her interest in puppetry and set design, and pursued philanthropic causes. She was elected to the American Academy and Institute of Letters. By the early 1990s Mary Frank was no longer making sculpture, having turned first to painting, then to painting hinged panels in the traditional form of religious triptychs. She fills sketchbooks with drawings and she also does photography.

Of her more recent work, noted feminist art historian Linda Nochlin says: “How rare it is, at the beginning of the second millennium, to discuss an artist in terms of feeling, of deep emotion. And yet there it is: Frank’s work speaks to our deepest and most commonly shared emotions, and does so in ways that are entirely unconventional and original, ways conceived through a lifetime of experience and knowledge, yet palpitating with the vitality of immediate discovery.” [6]

Notes:

[1] Millhouse to Kathleen Hutton, March 20, 2009, artist file, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[2] Paul Master-Karnik, “Foreword,” in Natural Histories: Mary Frank’s Sculpture, Prints, and Drawings, exhibition catalogue (Lincoln, MA: deCordova and Dana Museum and Park, 1988), 3.

[3] Eleanor Munro, Originals: American Women Artists (New York: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, 1979, Da Capo Press reprint 2000), 298.

[4] Hayden Herrera, Mary Frank (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1990), 60.

[5] Munro, Originals, 304.

[6] Linda Nochlin, Mary Frank: Encounters, exhibition catalogue (New York: Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2000), 9.