Roger Brown

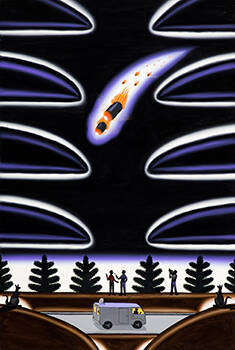

An informal group known as the Chicago Imagists emerged in the late 1960s, embraced familiar imagery, and frequently indulged in humorous statements about the complexity of modern life. Often incorporating kitsch elements in their work, on occasion they treated their subjects cynically. Along with Jim Nutt, Roger Brown (1941¬–1997) was one of the most colorful and distinctive members of the Chicago Imagists. “Although eccentricity, reliance on the vernacular, and an apparent compulsion toward narrative were characteristics common in some measure to all the imagists, Brown’s work exhibits one more crucial distinction: his subjects possess an obvious timeliness. Indeed, Brown’s works have frequently been likened to prewar American Scene painting in just this respect. By selecting contemporary subjects that are very much a ‘part of everybody’s experience of life,’ Brown achieves an immediate communication comparable to that of the Social Realists or Regionalists in the thirties…creating what one critic promptly identified as a ‘quintessentially American’ landscape for this time.” [1]

Brown was born in Hamilton, Alabama, but moved as a child across the state to Opelika. He was profoundly affected by his roots in the deep South, as described by art historian Mary Mathews Gedo: “Brown’s character—and his art—have been deeply impregnated by the experience of growing up in the rural South in a close-knit family committed to fundamentalist religious beliefs and practices. Although transient events, such as sights observed during vacation trips, invariably invade his paintings, the enduring elements of Brown’s personal style and iconography remain rooted in early childhood memories. … Such consistent stylistic features as the glowing nocturnal light…commemorate dramatic sky effects glimpsed by the sleepy future artist on trips home from evening revival meetings.” [2] Although his public school education lacked formal art lessons, he received some instruction from the wife of the school’s football coach from second to ninth grade. In high school, Brown made posters and helped out in theatrical productions. In fall 1960, he began David Lipscomb College in Nashville, Tennessee, thinking he would become a minister in the Church of Christ, the fundamentalist Christian religion in which he had been raised. Brown soon withdrew from Lipscomb and by 1962 had moved to Chicago in order to study art.

After studying commercial design at the American Academy of Art, Brown attended classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he earned bachelor of fine arts and master of fine arts degrees in 1968 and 1970 respectively. The culture of the school greatly influenced him and the other artists who became known as the Chicago Imagists. Brown credits his education in art and art history at the Art Institute as critical to his artistic development: “I remember being stuck trying to do imitation Matisses and imitation Picassos and getting bored. There was the need to get something more, but how do you get there? Having Ray [Yoshida] as a teacher helped me get there. Ray was the one who was able to make me put myself into my art.” Brown also learned from Yoshida about what was then termed “self-taught” art; in an interview he observed “there is a strong relationship between naïve painters like Joseph Yoakum and later medieval painters, as well as to Oriental landscape and Persian miniature painters.” [3] In 1968, Brown was included in an exhibition with other Art Institute students called “False Image,” a title chosen because their work was representational but not realistic. The following year Brown was included in several exhibitions at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, as well as a second “False Image” exhibition. Even before his graduate degree was awarded, the art dealer Phyllis Kind had decided to represent him.

In 1972 Roger Brown met George Veronda, an architect who encouraged Brown’s interest in and exploration of architectural themes and was his partner until Veronda’s death in 1984. Through Veronda’s influence, Brown developed an appreciation for the international style buildings of Mies van der Rohe. As Gedo comments, “the artist began to appreciate their beauty, especially the care with which Mies invariably worked out the patterning of his curtain walls. Brown soon realized the relevance of such rhythmic repetitions to his own artistic goals, and his canvases quickly began to reflect the fascination with patterning that has remained a constant in his art.” [4] That same year Brown began his Disaster Series and was represented in the Chicago Imagist Art exhibition held at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, which gave the stylistic label to Brown, Nutt, Ed Paschke and other artists in the show.

In a 1976 interview Brown explained his personal philosophy: “One of the things I have always thought is important is simplification. There has to be complexity in a painting, but to make things instantly readable is very important. … Reducing a certain form so that you can repeat it over and over again, and then continually adding new forms and getting more complex as you go along is what I am trying to do.” [5]

Throughout his career Brown remained very involved with the Chicago art scene at some cost to his reputation, according to critic John Yau, who noted that “given his use of vernacular imagery; his insistence on spatiality; his statements about the relationship between American and European art; his admiration for the work of Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keeffe, American Regionalists, and Early Modernists; and his adamant rejection of New York art styles since World War II, it is easy to see why, early in his career, many New York critics considered Brown outside the mainstream of contemporary art and thus a minor artist. … In New York parlance, Chicago Imagist, with its emphasis on locale, was understood as an updated version of American Regionalist. In so readily using the term, New York was acting out of its chauvinistic belief that it, New York, was central and everywhere else was subsidiary.” However, the heyday of Modernism was ending, and as Yau noted, “The emergence of independently minded, strong artists in Chicago, northern California, and elsewhere started the art world on the path to pluralism.”[6]

Despite his considerable art world success in the 1970s and 1980s, Brown was critical of what he termed mainstream art, which from his perspective was incorrectly dubbed superior to untrained or outsider artists. He became an avid collector of their work and supported projects involving them. In the late 1980s and 1990s Brown designed costumes and sets for the Chicago Opera, covers for Time magazine, and a public mural in the NBC Tower in Chicago. Shortly before his death from liver cancer in 1997, he had planned to buy a home in his native Alabama; it is now the Roger Brown Memorial Rock House Museum in Beulah. His generosity to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago was lifelong and included provisions for a study collection of his life’s work along with his homes and collections in Beulah, New Buffalo, Michigan, and La Conchita, California.

Notes:

[1] Timothy J. Garvey, “Garden Becomes Machine: Images of Suburbia in the Painting of Roger Brown,” Smithsonian Studies in American Art, 3, no. 3 (Summer 1989), 10.

[2] Mary Mathews Gedo, “An Autobiography in the Shape of Alabama: The Art of Roger Brown,” Art Criticism, 4, no. 3, (1988), 37–38.

[3] Brown, “A Talking Profile of the Artist,” in Roger Brown, exhibition catalogue (New York: George Braziller, Inc., in association with the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 1997), 93, and Brown quoted in Barry Blinderman, “A Conversation with Roger Brown,” Arts Magazine (May 1981), 99.

[4] Gedo, “An Autobiography,” 40.

[5] Brown quoted in Russell Bowman, “An Interview with Roger Brown,” Art in America (January 1978), 107.

[6] John Yau, “Roger Brown and Spectacle,” in Roger Brown, exhibition catalogue (New York: George Braziller, Inc. in association with the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 1997), 14–15.