Skip to main contentBiographyIn 1928, the artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi (1889–1953) took his second trip to Europe. He later recalled, “The trip proved a great stimulus, enlarging my scope and vision. Almost everybody on the other side was painting directly from the object, something I hadn’t done all these years. It was rather difficult to change my approach since up to then I had painted almost entirely from my imagination and my memories of the past.” [1]

Born in Okayama, Japan, Kuniyoshi came to America at the age of sixteen without clear plans for his future. [2] After he enrolled in high school in Los Angeles, a teacher suggested he try art school. He attended the Los Angeles School of Art, supporting himself by working in a hotel and as a farm laborer. In 1910, he moved to New York, registering first at the National Academy of Design before transferring to the more progressive Independent School of Art. He found his first artistic home, however, at the Art Students League in 1916, where he studied with Kenneth Hayes Miller and joined a group of forward-thinking young artists that included Reginald Marsh.

Over the next few years, Kuniyoshi embarked on a series of mysterious paintings of women, children, and cows inhabiting dream-like landscapes or interiors; see, for example, Dream, 1922, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Japan, and Boy Stealing Fruit, 1923, Columbus Museum of Art. In works such as Circus Girl Resting, 1925, Collection of Auburn University, and La Toilette, 1928, Fukutake Shoten Collection, Japan, the artist frequently painted nudes and women in various states of undress. His figures had round, sturdy bodies and disproportionately large eyes. The flattened space and tilted perspective in these paintings reveal the impact of Cubism as well as nineteenth-century American primitive painting, which he had begun collecting on summer trips to Ogunquit, Maine. In 1922, he had his first one-man show at Daniel Gallery in New York, a gallery that also represented the avant-garde American artists Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and John Marin.

In his paintings of women, the artist often included personal objects typically found on a dressing table such as hairbrushes or vases of flowers. The creation of these miniature still lifes in larger paintings gave rise to an interest in the subject on its own, and Kuniyoshi created a number of enigmatic still lifes in the 1920s and 1930s. He said, “I have assiduously collected throughout the years numerous objects of various shapes, textures, and colors because of their special appeal to me. … My approach to these objects, for painting purposes, is from the psychological as well as emotional viewpoint, setting them in a relationship and environment that creates an association stemming from personal experience.” [3]

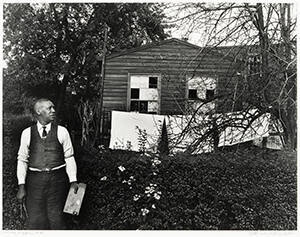

1929 proved to be an eventful year for Kuniyoshi. In that year, he began work on a house and studio in Woodstock, New York, a growing artists’ colony. He was also selected to participate in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art entitled “Paintings by Nineteen Living Americans,” to which he submitted the still life at Reynolda House. [4]

In 1933, Edith Halpert began showing Kuniyoshi’s work in her Downtown Gallery and Kuniyoshi began teaching at the Art Students League and the New School for Social Research. Despite growing recognition from the art world, the artist often encountered difficulties. He worked as a photographer to support himself and had some financial backing from the artist and collector Hamilton Easter Field, but he often found himself lacking secure income. He was personally popular with a group of progressive artists in New York and active in arts organizations, serving as president of the liberal American Artists’ Congress, but he sometimes had to fight to be included in exhibitions because of his Japanese heritage. Even in the progressive atmosphere of the Art Students League, there were some students who disapproved of his marriage to the American artist Katherine Schmidt; their marriage ended in divorce in 1932. [5] In 1931, he made his only trip to Japan to visit his ailing father, who died after Kuniyoshi returned to the United States. His mother died two years later.

The gravest challenges, however, came with the onset of World War II. Kuniyoshi was declared an enemy alien and confined to his apartment, and he faced the humiliating prospect of having several possessions, such as his camera, confiscated. He reacted by publicly declaring his allegiance to his adopted country and campaigning vigorously to support the United States war effort through the production of anti-Japanese propaganda. He also recorded speeches in Japanese urging the Japanese people to surrender.

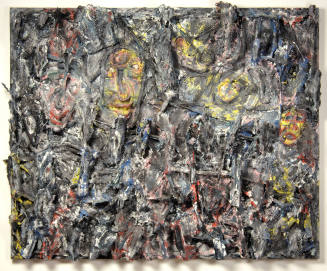

His paintings at the time often centered on solitary women, heavy-lidded and brooding, such as Somebody Tore My Poster, 1943, private collection. Art historians have suggested that they reflect his somber mood during the war years. He also continued to produce inscrutable still lifes, such as Room 110, 1944, Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, in which a vase, a picture fragment, and fruit are piled haphazardly on a table.

After the war, Kuniyoshi traveled with his second wife Sara Mazo Kuniyoshi and taught at universities in California, Minnesota, and Ohio. In 1948, the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted a retrospective of his work—the museum’s first retrospective of a living artist. It was a fitting tribute for an artist who had fought so long to be considered American. Speaking at the Museum of Modern Art in 1940, Kuniyoshi proclaimed “If the individual lives and works in a given local[e] for a length of time, regardless of nationality, work produced there becomes indigenous to that country.” [6] Kuniyoshi died in 1953, and was both mourned and lauded by his adopted country.

Notes:

[1] Kuniyoshi, quoted in Susan Lubowsky, Alexandra Munroe, Tom Wolf, Bert Winther, Takeo Uchiyama, Yasuo Kuniyoshi ([Tokyo], Japan: Nippon Television Network Corp., 1989), 201.

[2] Biographical information adapted from Susan Lubowsky, et al, Yasuo Kuniyoshi. There is some disagreement about the artist’s birth date. Some sources list 1893, but both Lubowsky and Gail Levin, “Between Two Worlds: Folk Culture, Identity, and the American Art of Yasuo Kuniyoshi.” Archives of American Art Journal, 43, 3/4 (2003): 2–17, list 1889.

[3] Kuniyoshi, quoted in Lubowsky et al, 26.

[4] Letter from Sara Mazo Kuniyoshi, Kuniyoshi’s second wife, to Susan Lubowsky, February 23, 1994, Reynolda House Museum of American Art object file.

[5] Jane Myers and Tom Wolf, The Shores of a Dream: Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s Early Work in America (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1996), 25.

[6] Kuniyoshi, quoted in Lubowsky et al, 204.

Yasuo Kuniyoshi

1889 - 1953

Born in Okayama, Japan, Kuniyoshi came to America at the age of sixteen without clear plans for his future. [2] After he enrolled in high school in Los Angeles, a teacher suggested he try art school. He attended the Los Angeles School of Art, supporting himself by working in a hotel and as a farm laborer. In 1910, he moved to New York, registering first at the National Academy of Design before transferring to the more progressive Independent School of Art. He found his first artistic home, however, at the Art Students League in 1916, where he studied with Kenneth Hayes Miller and joined a group of forward-thinking young artists that included Reginald Marsh.

Over the next few years, Kuniyoshi embarked on a series of mysterious paintings of women, children, and cows inhabiting dream-like landscapes or interiors; see, for example, Dream, 1922, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Japan, and Boy Stealing Fruit, 1923, Columbus Museum of Art. In works such as Circus Girl Resting, 1925, Collection of Auburn University, and La Toilette, 1928, Fukutake Shoten Collection, Japan, the artist frequently painted nudes and women in various states of undress. His figures had round, sturdy bodies and disproportionately large eyes. The flattened space and tilted perspective in these paintings reveal the impact of Cubism as well as nineteenth-century American primitive painting, which he had begun collecting on summer trips to Ogunquit, Maine. In 1922, he had his first one-man show at Daniel Gallery in New York, a gallery that also represented the avant-garde American artists Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and John Marin.

In his paintings of women, the artist often included personal objects typically found on a dressing table such as hairbrushes or vases of flowers. The creation of these miniature still lifes in larger paintings gave rise to an interest in the subject on its own, and Kuniyoshi created a number of enigmatic still lifes in the 1920s and 1930s. He said, “I have assiduously collected throughout the years numerous objects of various shapes, textures, and colors because of their special appeal to me. … My approach to these objects, for painting purposes, is from the psychological as well as emotional viewpoint, setting them in a relationship and environment that creates an association stemming from personal experience.” [3]

1929 proved to be an eventful year for Kuniyoshi. In that year, he began work on a house and studio in Woodstock, New York, a growing artists’ colony. He was also selected to participate in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art entitled “Paintings by Nineteen Living Americans,” to which he submitted the still life at Reynolda House. [4]

In 1933, Edith Halpert began showing Kuniyoshi’s work in her Downtown Gallery and Kuniyoshi began teaching at the Art Students League and the New School for Social Research. Despite growing recognition from the art world, the artist often encountered difficulties. He worked as a photographer to support himself and had some financial backing from the artist and collector Hamilton Easter Field, but he often found himself lacking secure income. He was personally popular with a group of progressive artists in New York and active in arts organizations, serving as president of the liberal American Artists’ Congress, but he sometimes had to fight to be included in exhibitions because of his Japanese heritage. Even in the progressive atmosphere of the Art Students League, there were some students who disapproved of his marriage to the American artist Katherine Schmidt; their marriage ended in divorce in 1932. [5] In 1931, he made his only trip to Japan to visit his ailing father, who died after Kuniyoshi returned to the United States. His mother died two years later.

The gravest challenges, however, came with the onset of World War II. Kuniyoshi was declared an enemy alien and confined to his apartment, and he faced the humiliating prospect of having several possessions, such as his camera, confiscated. He reacted by publicly declaring his allegiance to his adopted country and campaigning vigorously to support the United States war effort through the production of anti-Japanese propaganda. He also recorded speeches in Japanese urging the Japanese people to surrender.

His paintings at the time often centered on solitary women, heavy-lidded and brooding, such as Somebody Tore My Poster, 1943, private collection. Art historians have suggested that they reflect his somber mood during the war years. He also continued to produce inscrutable still lifes, such as Room 110, 1944, Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, in which a vase, a picture fragment, and fruit are piled haphazardly on a table.

After the war, Kuniyoshi traveled with his second wife Sara Mazo Kuniyoshi and taught at universities in California, Minnesota, and Ohio. In 1948, the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted a retrospective of his work—the museum’s first retrospective of a living artist. It was a fitting tribute for an artist who had fought so long to be considered American. Speaking at the Museum of Modern Art in 1940, Kuniyoshi proclaimed “If the individual lives and works in a given local[e] for a length of time, regardless of nationality, work produced there becomes indigenous to that country.” [6] Kuniyoshi died in 1953, and was both mourned and lauded by his adopted country.

Notes:

[1] Kuniyoshi, quoted in Susan Lubowsky, Alexandra Munroe, Tom Wolf, Bert Winther, Takeo Uchiyama, Yasuo Kuniyoshi ([Tokyo], Japan: Nippon Television Network Corp., 1989), 201.

[2] Biographical information adapted from Susan Lubowsky, et al, Yasuo Kuniyoshi. There is some disagreement about the artist’s birth date. Some sources list 1893, but both Lubowsky and Gail Levin, “Between Two Worlds: Folk Culture, Identity, and the American Art of Yasuo Kuniyoshi.” Archives of American Art Journal, 43, 3/4 (2003): 2–17, list 1889.

[3] Kuniyoshi, quoted in Lubowsky et al, 26.

[4] Letter from Sara Mazo Kuniyoshi, Kuniyoshi’s second wife, to Susan Lubowsky, February 23, 1994, Reynolda House Museum of American Art object file.

[5] Jane Myers and Tom Wolf, The Shores of a Dream: Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s Early Work in America (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1996), 25.

[6] Kuniyoshi, quoted in Lubowsky et al, 204.

Person TypeIndividual