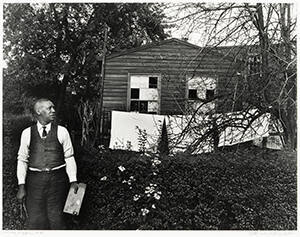

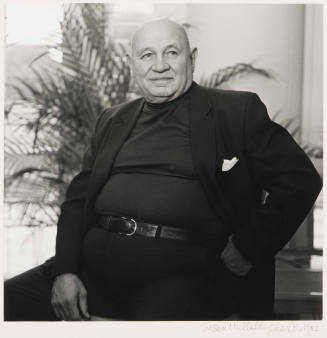

Skip to main contentBiographyHorace Pippin was born in 1888 in West Chester, Pennsylvania. Other notable American artists from this area of the Brandywine River Valley include Edward Hicks (a nineteenth-century white Quaker preacher who, as a self-taught artist, has sometimes been compared to Pippin) and three generations of the Wyeth family. Horace Pippin, an African American laborer and a disabled World War I veteran, had managed to produce oil paintings over the previous decade despite his paralyzed right arm. The well-known illustrator Nathaniel (N.C.) Wyeth was an early and instant admirer of Pippin’s work, which he first saw displayed in the 1937 West Chester County Art Association annual exhibition. Wyeth convinced the Association’s president, Dr. Christian Brinton, to sponsor a one-man exhibition of Pippin in June 1937. At this exhibition, almost all of Pippin’s work sold. Wealthy arts patrons on Philadelphia’s Main Line began to exhibit interest in his work and, the following year, four of his paintings were included in the “Masters of Popular Painting” exhibition organized by Holger Cahill at the Museum of Modern Art. “As the American art world sought ‘primitive’ or naïve art in the 1930s and 1940s, both for its emotional honesty and formal parallels with Modernism, it championed unschooled artists William Edmondson, Anna Mary Robertson (Grandma) Moses, Joseph Pickett, and Horace Pippin as practitioners of this style”. [1] Pippin’s work attracted the interest of art dealer Hudson Walker but he was unable to sell his work from the MOMA exhibition. In 1939, Robert Carlen of Robert Carlen Galleries in Philadelphia became Pippin’s art dealer, and it was at his gallery that the important collector Albert Barnes saw and acquired Pippin’s work. Carlen remained Pippin’s dealer for the rest of his life, providing him with supplies, cash and sales to individuals and museums across the country.

Although born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Pippin had moved away as a child to Gosen, New York. In his biographic remarks he recalled that, as a schoolboy, he drew pictures to illustrate his class notes (for which he was punished), and that he won a mail-order art contest advertised in the newspaper and received a much-cherished prize of crayon and paint sets. Pippin also said that one of his employers had noticed the teenager’s talent after finding a sketch of himself that Pippin had drawn; he promised to send him to art school, but Pippin had no opportunity to do so as he had to work to support his widowed mother. After several jobs as a laborer, Pippin became a porter at Goshen’s St. Elmo Hotel for seven years. After his mother died in 1911, Pippin moved to Paterson, New Jersey, and worked at the Fidelity Storage House. Among the furniture and objects he prepared for shipping across the country, he saw oil paintings for the first time. In 1917, Pippin enlisted in the Army. He later said, “The good old U.S.A was in trouble with Germany and to do our duty to her we had to leave her.” [2]

Pippin joined a black regiment, the New York State 15th National Guard, later the famous 369th Infantry Regiment, known by both the French and the German troops as the “Hell-Fighters.” During the war, the artist kept an illustrated war diary, making sketches and storing up memories that he would depict in paintings many years later. Unfortunately, only a few pages of his diary remain. Because the war was not yet over when Pippin was honorably discharged, he destroyed his diary so as not to risk leaking information to the enemy. Pippin would mourn the loss of his diary but he drew upon his memories of his observations in his paintings of war. The 369th was the first African-American unit shipped overseas, arriving in Brest, France, in late December 1917, by which time Pippin had become a corporal. There were no plans to use African American soldiers in combat, so the 369th was put to work that winter laying over five hundred miles of track in preparation for transporting supplies to the front. The major German offensive that March required the American troops already on the ground in Europe to be assigned to strengthen either the British or French armies. The British, like the Americans, were uncomfortable with black soldiers fighting along whites, so Pippin’s regiment was assigned to the French 16th Division. Pippin wrote, “After a month’s training learning the French rifle, the 369th was sent into action”. [3] The regiment was kept almost continuously at the front, at one time fighting one hundred and thirty days without relief, due to their effectiveness as a fighting force but also because there was no provision for African Americans in the rear respite zones. In October, Pippin was shot in the shoulder by a sniper. After several months in recovery, he was discharged in May 1919 with an almost entirely useless right arm. Until his artistic career proved successful, Pippin’s disability check would be the only income he could bring in to support himself and his wife Jennie Featherstone Wade (whom he had married in 1920), as he could not do physical work.

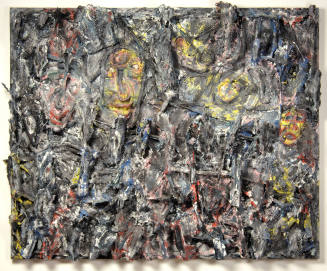

His war service was a source of great pride to Pippin, but, “like millions of other African Americans who expectantly joined the war effort in the belief that their sacrifices would change white American attitudes, Pippin returned home not only with images of the destructiveness of modern warfare indelibly printed in his mind, but also sharing in the disappointment and frustration of other African American soldiers who, upon their return to the states, encountered entrenched racism.” [4] Upon his honorable discharge from the army he had been awarded the French Croix de Guerre but would wait until 1945 to receive his own country’s Purple Heart. Pippin’s painting Mr. Prejudice (1943) and other works reflect his insight into the failure of American society to overcome racism. Art historian Judith Wilson says that “. . . Pippin’s 1930s canvases on the war theme describe the violence of modern warfare, while his 1940s war-related canvases condemn the hypocrisy of a segregated nation playing the role of international guardian of freedom.” [5]

In addition to his images from the war, Pippin’s subjects would range from the historical featuring John Brown and Abraham Lincoln, among others, to portraits he painted of his wealthy patrons, his family, his friends, and himself. He showed African Americans going about daily activities during his time as well as his grandmother’s. His later paintings intensified in color and he produced a number of floral still lifes and detailed interiors. He also painted deeply religious and anti-war images, such as his four “Holy Mountain” paintings.

In the nine years of meteoric fame before his death in 1946, Horace Pippin became a nationally recognized and productive artist whose works were acquired by wealthy collectors such as Albert Barnes, Duncan Phillips, and Joseph Hirshhorn, among other famous people. His paintings were reproduced in national publications such as Time, Newsweek and Life magazines. He withstood as well as he could the intense pressure from the expectations that came with such fame, although it destroyed his wife’s peace of mind. His success with wealthy white patrons and collectors was not regarded favorably by some African-American critics and artists who had received formal training. Then again, Pippin’s collectors, such as Barnes, were not comfortable with works such as Mr. Prejudice, preferring Pippin’s style to his message. Romare Bearden wrote, “That Pippin owes nothing to earlier artists is an important aspect of his uniqueness. He is wholly an African-American artist. His life as a black American is the basis of everything he painted. When he at last emerged from the poverty-ridden role of a disabled black man on the wings of his own artistic vision, his achievements grew more and more impressive as he continued to develop.” [6]

Notes:

[1] Monahan, Ann. “I Tell My Heart,” in American Art Review, p. 102.

[2] Rodman, Selden & Carole Cleaver, Horace Pippin: The Artist as Black American, p. 34.

[3] Rodman, p. 40.

[4] Roberts, John W. “Horace Pippin and African American Vernacular,” Cultural Critique, no. 41 (Winter, 1999), p. 28.

[5] Wilson, Judith. “Scenes of War,” in I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin, p. 64.

[6] Bearden, Romare & Harry Henderson. Six Black Masters of American Art. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., 1972, p. 369.

Horace Pippin

1888 - 1946

Although born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Pippin had moved away as a child to Gosen, New York. In his biographic remarks he recalled that, as a schoolboy, he drew pictures to illustrate his class notes (for which he was punished), and that he won a mail-order art contest advertised in the newspaper and received a much-cherished prize of crayon and paint sets. Pippin also said that one of his employers had noticed the teenager’s talent after finding a sketch of himself that Pippin had drawn; he promised to send him to art school, but Pippin had no opportunity to do so as he had to work to support his widowed mother. After several jobs as a laborer, Pippin became a porter at Goshen’s St. Elmo Hotel for seven years. After his mother died in 1911, Pippin moved to Paterson, New Jersey, and worked at the Fidelity Storage House. Among the furniture and objects he prepared for shipping across the country, he saw oil paintings for the first time. In 1917, Pippin enlisted in the Army. He later said, “The good old U.S.A was in trouble with Germany and to do our duty to her we had to leave her.” [2]

Pippin joined a black regiment, the New York State 15th National Guard, later the famous 369th Infantry Regiment, known by both the French and the German troops as the “Hell-Fighters.” During the war, the artist kept an illustrated war diary, making sketches and storing up memories that he would depict in paintings many years later. Unfortunately, only a few pages of his diary remain. Because the war was not yet over when Pippin was honorably discharged, he destroyed his diary so as not to risk leaking information to the enemy. Pippin would mourn the loss of his diary but he drew upon his memories of his observations in his paintings of war. The 369th was the first African-American unit shipped overseas, arriving in Brest, France, in late December 1917, by which time Pippin had become a corporal. There were no plans to use African American soldiers in combat, so the 369th was put to work that winter laying over five hundred miles of track in preparation for transporting supplies to the front. The major German offensive that March required the American troops already on the ground in Europe to be assigned to strengthen either the British or French armies. The British, like the Americans, were uncomfortable with black soldiers fighting along whites, so Pippin’s regiment was assigned to the French 16th Division. Pippin wrote, “After a month’s training learning the French rifle, the 369th was sent into action”. [3] The regiment was kept almost continuously at the front, at one time fighting one hundred and thirty days without relief, due to their effectiveness as a fighting force but also because there was no provision for African Americans in the rear respite zones. In October, Pippin was shot in the shoulder by a sniper. After several months in recovery, he was discharged in May 1919 with an almost entirely useless right arm. Until his artistic career proved successful, Pippin’s disability check would be the only income he could bring in to support himself and his wife Jennie Featherstone Wade (whom he had married in 1920), as he could not do physical work.

His war service was a source of great pride to Pippin, but, “like millions of other African Americans who expectantly joined the war effort in the belief that their sacrifices would change white American attitudes, Pippin returned home not only with images of the destructiveness of modern warfare indelibly printed in his mind, but also sharing in the disappointment and frustration of other African American soldiers who, upon their return to the states, encountered entrenched racism.” [4] Upon his honorable discharge from the army he had been awarded the French Croix de Guerre but would wait until 1945 to receive his own country’s Purple Heart. Pippin’s painting Mr. Prejudice (1943) and other works reflect his insight into the failure of American society to overcome racism. Art historian Judith Wilson says that “. . . Pippin’s 1930s canvases on the war theme describe the violence of modern warfare, while his 1940s war-related canvases condemn the hypocrisy of a segregated nation playing the role of international guardian of freedom.” [5]

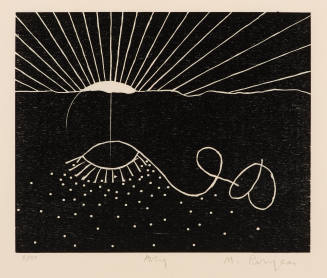

In addition to his images from the war, Pippin’s subjects would range from the historical featuring John Brown and Abraham Lincoln, among others, to portraits he painted of his wealthy patrons, his family, his friends, and himself. He showed African Americans going about daily activities during his time as well as his grandmother’s. His later paintings intensified in color and he produced a number of floral still lifes and detailed interiors. He also painted deeply religious and anti-war images, such as his four “Holy Mountain” paintings.

In the nine years of meteoric fame before his death in 1946, Horace Pippin became a nationally recognized and productive artist whose works were acquired by wealthy collectors such as Albert Barnes, Duncan Phillips, and Joseph Hirshhorn, among other famous people. His paintings were reproduced in national publications such as Time, Newsweek and Life magazines. He withstood as well as he could the intense pressure from the expectations that came with such fame, although it destroyed his wife’s peace of mind. His success with wealthy white patrons and collectors was not regarded favorably by some African-American critics and artists who had received formal training. Then again, Pippin’s collectors, such as Barnes, were not comfortable with works such as Mr. Prejudice, preferring Pippin’s style to his message. Romare Bearden wrote, “That Pippin owes nothing to earlier artists is an important aspect of his uniqueness. He is wholly an African-American artist. His life as a black American is the basis of everything he painted. When he at last emerged from the poverty-ridden role of a disabled black man on the wings of his own artistic vision, his achievements grew more and more impressive as he continued to develop.” [6]

Notes:

[1] Monahan, Ann. “I Tell My Heart,” in American Art Review, p. 102.

[2] Rodman, Selden & Carole Cleaver, Horace Pippin: The Artist as Black American, p. 34.

[3] Rodman, p. 40.

[4] Roberts, John W. “Horace Pippin and African American Vernacular,” Cultural Critique, no. 41 (Winter, 1999), p. 28.

[5] Wilson, Judith. “Scenes of War,” in I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin, p. 64.

[6] Bearden, Romare & Harry Henderson. Six Black Masters of American Art. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., 1972, p. 369.

Person TypeIndividual