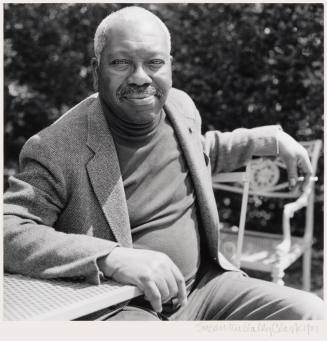

Jacob Lawrence

A great storyteller, Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) once claimed in an interview, “Form is just as important as content.” The stories he painted were about the history of blacks in America and the African-American experience. He rendered them in a uniquely personal style that has been called “expressive cubism.” [1]

Despite the fact that he was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, Lawrence is intimately associated with Harlem, where his family moved in 1930. His art education began early with Charles Alston at the Harlem Art Workshop, sponsored at first by the College Art Association and then the Works Progress Administration. For eighteen months, he was affiliated with the easel program of the WPA Federal Art Project. Even though the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance had passed, Lawrence was exposed to a community of artists and writers who celebrated the accomplishments of African Americans. Precocious, he painted at the age of twenty the first of his slave histories, which focused on the Haitian revolutionary figure Toussaint L’Ouverture. Others in the series deal with Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. Lawrence carefully researched their life stories, which he illustrated in small tempera paintings bearing captions of his own devising. In 1940, he presented a more contemporary theme, the twentieth-century migration of blacks from the South to the North.

Success came early to Lawrence; the Toussaint paintings were exhibited at the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1938; he was awarded a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1940, which was renewed the following year; and he was the first African American to have a one-man exhibition at a major New York gallery, the Downtown Gallery, in 1941. During World War II, he served in the United States Coast Guard and was stationed in St. Augustine and Boston before tours to Europe, the Near East, and India. Following his discharge, Lawrence taught one summer at the avant-garde Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where Josef Albers headed the art department and became his mentor.

With his wife, the painter Gwendolyn Knight, he lived first in Brooklyn, and then on the fringes of Harlem. Many awards and artist-in-residencies came his way, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, and teaching at Brandeis University, the Art Students League, and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine for six summers. He undertook commissions for Fortune and Time magazines. During the 1970s, he taught at the University of Washington in Seattle, which induced him to break ties with New York.

Over his long and productive career, Lawrence returned repeatedly to themes of struggle, learning, building, and community. His two-dimensional figures were largely African Americans, portrayed simply but heroically, and typically painted with tempera paints or gouache. His style employs such Cubist-derived devices as tilted space, distorted proportions, and emphatic juxtapositions of color. For him, both form and content draw from the same source. In his acceptance speech for an award from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Lawrence declared modestly: “If I have achieved a degree of success as a creative artist, it is mainly due to the black experience which is our heritage—an experience which gives inspiration, motivation, and stimulation. I was inspired by the black aesthetic by which we are surrounded, motivated to manipulate form, color, space, line and texture to depict our life, and stimulated by the beauty and poignancy of our environment. We do not forget…that encouragement which came from the black community.” [2]

Notes:

[1] Lawrence, quoted in Lowery Stokes Sims, “The Structure of Narrative: Form and Content in Jacob Lawrence’s Builders Paintings, 1946–1998,” in Peter T. Nesbitt, ed. Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2000), 201, and Patricia Hills, “Jacob Lawrence’s Expressive Cubism,” in Ellen Harkins Wheat, Jacob Lawrence: American Painter (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1986), 15.

[2] Lawrence, quoted in Wheat, Jacob Lawrence, 142.