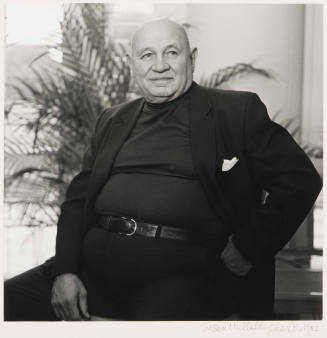

Skip to main contentBiographyGeorge Bellows (1882–1925), a major figure in early twentieth-century art associated with the Ashcan School, was already an established artist, a recipient of numerous painting awards, and a member of the National Academy of Design by the time he began experimenting with lithography in 1916. The artist purchased his own lithography press in the winter of 1915–1916 and installed it in his home studio, pulling his first prints himself. In 1916, he began working with the printer George Miller, whose skills helped the artist develop his facility with the medium. The following year, Bellows wrote to a friend, “This is great work for night and dark days, of which there are too many here in New York in winter, and I am busy as the proverbial bee.” [1]

Bellows, an Ohio native, had arrived in New York in 1904 at the age of twenty-two. Although he had drawn avidly since childhood, his formal training had been limited to a few classes at Ohio State University. Once he arrived in Manhattan, he enrolled immediately in William Merritt Chase’s art school, where Robert Henri was his instructor. Bellows and Henri developed a strong friendship, and the younger artist found himself drawn into the informal circle of artists known as the Ashcan School. He took to heart Henri’s credo to depict the urban environment with vigor and intensity. Some of his first New York subjects included the excavation of land for the construction of Pennsylvania Station and urban youth swimming along the shores of the Hudson and East Rivers, executed in an active, brushy style.

The subject that first brought him acclaim, however, was boxing. Bellows was himself an avid sportsman who had played baseball in college and in semi-professional leagues in New York. [2] In 1907, he began to visit boxing clubs, and he found a dynamic subject for paintings in their gritty environments. In such works as Stag at Sharkey’s, 1909, Cleveland Museum of Art, Club Night, 1907, and Both Members of this Club, 1909, both National Gallery of Art, he depicted the bloodied, muscled bodies of the boxers spotlit against the dark background of the arena. The crudely-rendered faces of the spectators emphasize the seediness of the clubs. Later in his career, he created more refined images of tennis and polo matches.

Bellows managed to navigate successfully between traditional artistic institutions and progressive groups such as Henri’s circle of friends. Despite his friendship with Henri and other members of the Ashcan School, he did not participate in the independent exhibition organized by the group called The Eight at Macbeth Galleries in 1908. The next year, he was elected an associate member of the very conventional National Academy of Design. He did, however, help to organize the Armory Show of 1913, which showcased the work of American painters, including him, as well as more avant-garde artists from Europe. Although he supported himself initially by working as a magazine illustrator and an instructor at the Art Students League, by 1909 his paintings were selling and, in addition, he began to be in demand for portrait commissions.

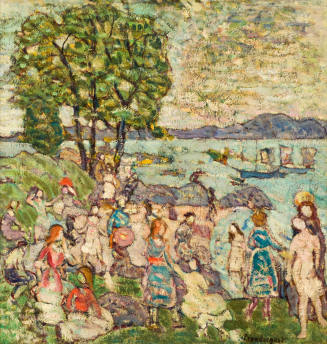

Having achieved enough financial success to support himself as a fine artist, Bellows began summering in such picturesque destinations as Monhegan Island, Maine, Middletown and Newport, Rhode Island, and Woodstock, New York. He painted in all of these places: landscapes and shipyards in Maine, tennis matches in Rhode Island, and intimate portraits of his wife and two daughters in the home they eventually built in Woodstock. His portraits owe a debt to the heroes of the American realists, Frans Hals and Diego Velazquez, and to his own personal artistic hero, Thomas Eakins.

Bellows was not as political as other members of the Ashcan School, especially John Sloan, but he did create pieces that expressed his horror of such contemporary events as the lynching of African Americans and the atrocities of World War I, along with his distaste for religious fundamentalism and his sympathy for the working classes. The best known of these was the painting Cliff Dwellers, 1913, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which depicted the crowded conditions in a gritty but vibrant tenement neighborhood on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. In an interview conducted in 1912, the artist explained his approach to art: “I can’t see anything in the worship of beauty which some people seek to develop. Beauty is easy to paint; just as easy as something grotesque. What really counts is interest.” [3]

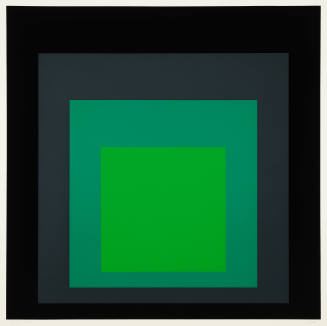

Cliff Dwellers was actually a reworked version of an earlier lithograph that was published in the socialist journal The Masses under the title Why Don’t They Go to the Country for a Vacation?. The ironic title might have been a wry acknowledgement of the artist’s own abilities to escape the overheated city in the summertime. The connection between Cliff Dwellers and Why Don’t They Go to the Country for a Vacation? demonstrates the complex relationship between Bellows’s paintings, prints, and drawings. Sometimes the artist revised earlier paintings as lithographs, and sometimes he turned lithograph subjects into paintings. He revisited subjects from drawings executed years earlier and turned them into prints. His restless, energetic personality also led him to experiment with painting theories such as the color theories of Jay Hambidge and Hardesty Maratta and a compositional theory called Dynamic Symmetry. These experiments might help to explain the stylized appearance of his later work.

Bellows died unexpectedly at the age of forty-two of a ruptured appendix, and the painting world mourned the loss of an enormous talent. His career as a lithographer had lasted less than ten years, but in that time he succeeded in bringing new attention to a medium that artists such as Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, Stuart Davis, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg would take up enthusiastically over subsequent decades of the twentieth century.

Notes:

[1] Jane Myers and Linda Ayres, George Bellows: The Artist and His Lithographs (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1988), 9 and 15.

[2] Charles H. Morgan, George Bellows: Painter of America (New York: Reynal and Company, 1965), 29 and 44.

[3] Bellows, quoted in Morgan, George Bellows, 158.

George Wesley Bellows

1882 - 1925

Bellows, an Ohio native, had arrived in New York in 1904 at the age of twenty-two. Although he had drawn avidly since childhood, his formal training had been limited to a few classes at Ohio State University. Once he arrived in Manhattan, he enrolled immediately in William Merritt Chase’s art school, where Robert Henri was his instructor. Bellows and Henri developed a strong friendship, and the younger artist found himself drawn into the informal circle of artists known as the Ashcan School. He took to heart Henri’s credo to depict the urban environment with vigor and intensity. Some of his first New York subjects included the excavation of land for the construction of Pennsylvania Station and urban youth swimming along the shores of the Hudson and East Rivers, executed in an active, brushy style.

The subject that first brought him acclaim, however, was boxing. Bellows was himself an avid sportsman who had played baseball in college and in semi-professional leagues in New York. [2] In 1907, he began to visit boxing clubs, and he found a dynamic subject for paintings in their gritty environments. In such works as Stag at Sharkey’s, 1909, Cleveland Museum of Art, Club Night, 1907, and Both Members of this Club, 1909, both National Gallery of Art, he depicted the bloodied, muscled bodies of the boxers spotlit against the dark background of the arena. The crudely-rendered faces of the spectators emphasize the seediness of the clubs. Later in his career, he created more refined images of tennis and polo matches.

Bellows managed to navigate successfully between traditional artistic institutions and progressive groups such as Henri’s circle of friends. Despite his friendship with Henri and other members of the Ashcan School, he did not participate in the independent exhibition organized by the group called The Eight at Macbeth Galleries in 1908. The next year, he was elected an associate member of the very conventional National Academy of Design. He did, however, help to organize the Armory Show of 1913, which showcased the work of American painters, including him, as well as more avant-garde artists from Europe. Although he supported himself initially by working as a magazine illustrator and an instructor at the Art Students League, by 1909 his paintings were selling and, in addition, he began to be in demand for portrait commissions.

Having achieved enough financial success to support himself as a fine artist, Bellows began summering in such picturesque destinations as Monhegan Island, Maine, Middletown and Newport, Rhode Island, and Woodstock, New York. He painted in all of these places: landscapes and shipyards in Maine, tennis matches in Rhode Island, and intimate portraits of his wife and two daughters in the home they eventually built in Woodstock. His portraits owe a debt to the heroes of the American realists, Frans Hals and Diego Velazquez, and to his own personal artistic hero, Thomas Eakins.

Bellows was not as political as other members of the Ashcan School, especially John Sloan, but he did create pieces that expressed his horror of such contemporary events as the lynching of African Americans and the atrocities of World War I, along with his distaste for religious fundamentalism and his sympathy for the working classes. The best known of these was the painting Cliff Dwellers, 1913, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which depicted the crowded conditions in a gritty but vibrant tenement neighborhood on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. In an interview conducted in 1912, the artist explained his approach to art: “I can’t see anything in the worship of beauty which some people seek to develop. Beauty is easy to paint; just as easy as something grotesque. What really counts is interest.” [3]

Cliff Dwellers was actually a reworked version of an earlier lithograph that was published in the socialist journal The Masses under the title Why Don’t They Go to the Country for a Vacation?. The ironic title might have been a wry acknowledgement of the artist’s own abilities to escape the overheated city in the summertime. The connection between Cliff Dwellers and Why Don’t They Go to the Country for a Vacation? demonstrates the complex relationship between Bellows’s paintings, prints, and drawings. Sometimes the artist revised earlier paintings as lithographs, and sometimes he turned lithograph subjects into paintings. He revisited subjects from drawings executed years earlier and turned them into prints. His restless, energetic personality also led him to experiment with painting theories such as the color theories of Jay Hambidge and Hardesty Maratta and a compositional theory called Dynamic Symmetry. These experiments might help to explain the stylized appearance of his later work.

Bellows died unexpectedly at the age of forty-two of a ruptured appendix, and the painting world mourned the loss of an enormous talent. His career as a lithographer had lasted less than ten years, but in that time he succeeded in bringing new attention to a medium that artists such as Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, Stuart Davis, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg would take up enthusiastically over subsequent decades of the twentieth century.

Notes:

[1] Jane Myers and Linda Ayres, George Bellows: The Artist and His Lithographs (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum, 1988), 9 and 15.

[2] Charles H. Morgan, George Bellows: Painter of America (New York: Reynal and Company, 1965), 29 and 44.

[3] Bellows, quoted in Morgan, George Bellows, 158.

Person TypeIndividual