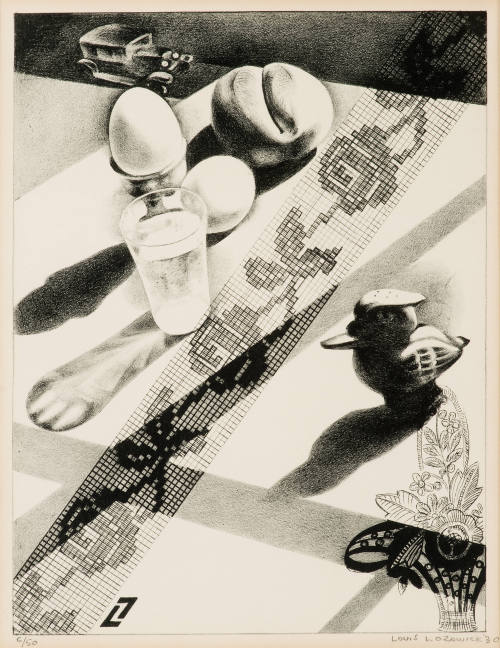

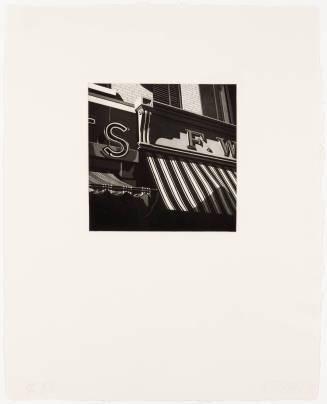

Skip to main contentBiographyAlthough he also painted, Louis Lozowick (1892–1973) is more widely recognized for magnificently tonal lithographs that celebrate the Machine Age. Lithography, long associated with journalism and commercial production, came into its own as a fine art medium in the early decades of the twentieth century. Enjoyed by artists since its inception in the mid-nineteenth century, lithography allowed them to draw directly on a printing matrix, instead of laboriously carving into wood or etching into metal. In the years between World War I and II, Lozowick was one of a growing number of American artists who embraced lithography and used the process for thoroughly modern imagery.

Lozowick was born in Ludvinovka, Ukraine and, while still a youth, began art studies in Kiev. In 1906, he left Russia for America and lived in New Jersey where he attended high school. He studied at the National Academy of Design between 1912 and 1915, and graduated three years later from Ohio State University with Phi Beta Kappa honors. He spent 1918 in the United States military. Following his discharge, he went to Paris where he connected with the expanding international community of artists. In 1920, he moved to Berlin, began his series focusing on cities, and in 1923 made his first lithograph. The following year, he returned to the United States and settled in New York, where he became involved in the New Masses, a leftist publication in which John Sloan, William Carlos Williams, and Theodore Dreiser were involved. He was one of the organizers of the 1927 Machine Age Exposition, and authored an accompanying essay, “The Americanization of Art.” During the Depression, he was an administrator in several art-related programs of the New Deal, but afterward became disillusioned about the legacy of the Progressive Era. He became active in the American Artists’ Congress, a group opposed to war and fascism.

For Lozowick, lithography was the ideal medium, but he did not work alone. He drew his design with special crayons on a carefully prepared surface, traditionally a particular kind of stone or a zinc plate, but relied on a well-versed printer to facilitate the actual production of the prints. Usually done in fairly small editions, many of Lozowick’s prints were made with the assistance of George C. Miller, who also worked with George Bellows, Thomas Hart Benton, and Childe Hassam. Another of the printer’s collaborators, Prentiss Taylor, described Miller’s workshop: “It did not take long to learn that one of the great blessings of the place was that George made no aesthetic judgments. He did not know stylistic prejudices. …The creative aspects were entirely the realm of the artist. He gave the neophyte, the hack, the well-known the best printing that could be brought from the zinc plate or the stone.” [1] Between 1928 and 1930 Lozowick produced about seventy lithographs, one-third of his entire output.

Throughout his long career, Lozowick maintained a keen interest in European trends. He was especially interested in Cubism, Constructivism, and the Russian avant-garde, even publishing Modern Russian Art. In his early paintings and prints, he frequently portrayed the industrial might of his adopted home, using distorted perspectives to heighten the visual impact of his images. Dark skies and deep shadows lent a feeling of foreboding. Late in his career, he turned to landscape and figure subjects.

Notes:

[1] Taylor, quoted in Janet Flint, George Miller and American Lithography (Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art, 1976), unpaginated.

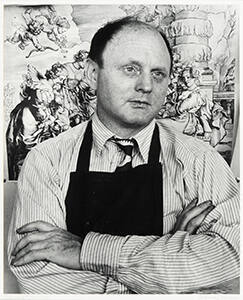

Louis Lozowick

1892 - 1973

Lozowick was born in Ludvinovka, Ukraine and, while still a youth, began art studies in Kiev. In 1906, he left Russia for America and lived in New Jersey where he attended high school. He studied at the National Academy of Design between 1912 and 1915, and graduated three years later from Ohio State University with Phi Beta Kappa honors. He spent 1918 in the United States military. Following his discharge, he went to Paris where he connected with the expanding international community of artists. In 1920, he moved to Berlin, began his series focusing on cities, and in 1923 made his first lithograph. The following year, he returned to the United States and settled in New York, where he became involved in the New Masses, a leftist publication in which John Sloan, William Carlos Williams, and Theodore Dreiser were involved. He was one of the organizers of the 1927 Machine Age Exposition, and authored an accompanying essay, “The Americanization of Art.” During the Depression, he was an administrator in several art-related programs of the New Deal, but afterward became disillusioned about the legacy of the Progressive Era. He became active in the American Artists’ Congress, a group opposed to war and fascism.

For Lozowick, lithography was the ideal medium, but he did not work alone. He drew his design with special crayons on a carefully prepared surface, traditionally a particular kind of stone or a zinc plate, but relied on a well-versed printer to facilitate the actual production of the prints. Usually done in fairly small editions, many of Lozowick’s prints were made with the assistance of George C. Miller, who also worked with George Bellows, Thomas Hart Benton, and Childe Hassam. Another of the printer’s collaborators, Prentiss Taylor, described Miller’s workshop: “It did not take long to learn that one of the great blessings of the place was that George made no aesthetic judgments. He did not know stylistic prejudices. …The creative aspects were entirely the realm of the artist. He gave the neophyte, the hack, the well-known the best printing that could be brought from the zinc plate or the stone.” [1] Between 1928 and 1930 Lozowick produced about seventy lithographs, one-third of his entire output.

Throughout his long career, Lozowick maintained a keen interest in European trends. He was especially interested in Cubism, Constructivism, and the Russian avant-garde, even publishing Modern Russian Art. In his early paintings and prints, he frequently portrayed the industrial might of his adopted home, using distorted perspectives to heighten the visual impact of his images. Dark skies and deep shadows lent a feeling of foreboding. Late in his career, he turned to landscape and figure subjects.

Notes:

[1] Taylor, quoted in Janet Flint, George Miller and American Lithography (Washington, DC: National Museum of American Art, 1976), unpaginated.

Person TypeIndividual