Skip to main contentBiographyAbstract Expressionism is frequently touted as America’s first homegrown art movement. Yet its roots revert to Surrealism, especially the variant known as automatism, which emphasized the role of the subconscious in the creation of artwork. As promulgated by André Breton and André Masson, automatism encouraged artists to draw by allowing the hand to move freely across the paper, accepting both chance and accident as compositional tools. The drip paintings of Jackson Pollock and the collages of Robert Motherwell (1915–1991) were natural outgrowths of this method. In addition, Motherwell’s work was responsive to the modernists Pablo Picasso for collage and Henri Matisse for bold, silhouetted shapes.

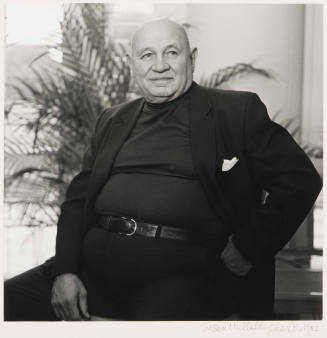

A product of the American West who figured prominently in the New York art world, Motherwell was born in Aberdeen, Washington, and spent parts of his childhood in California and Utah. After studying at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco for a year, he attended Stanford University, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy in 1937. Subsequently, for a year, he continued to study philosophy at the Graduate School of the Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. In 1939, he moved to New York, where Columbia University professor Meyer Shapiro introduced him to some of the European Surrealists who were living in exile. After experimenting with automatic drawings, he began making collages, which were shown at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in 1944.

New York in the 1940s was a vibrant place, and Motherwell began to interact with other artists working abstractedly and on a large scale. He became friendly with Mark Rothko, William Baziotes, and, in particular, the sculptor David Smith. During the summer of 1945, he taught at Black Mountain College, near Asheville, North Carolina. He made several trips to Mexico and became enamored with Spanish culture and history and, in 1948, embarked on his signature series, entitled Elegy to the Spanish Republic. Ominous black forms, which are metaphors for the strife and suffering of the times, dominate these large canvases. Unlike his fellow Abstract Expressionists, however, there is content in Motherwell’s art—not narrative or anecdotal—but art that is endowed with meaning. To him, “Black is death; white is life, éclat.” Other series, like Je t’aime with its bold calligraphy across canvases, unabashedly violate abstraction. In an interview, he explained: “Yes, painting is exactly a metaphor for reality. I do think there are references. I think the so-called ‘abstractness’ of modern art is not that it is about things, but that it’s an art really in the tradition of French Symbolist poetry, which is to say, an art that refuses to spell everything out. It’s a kind of shorthand, where a great deal is assumed.” [1]

For Motherwell, collage making was a release from large abstract painting as well as an indulgence in spontaneity. “Most of the papers I use in my collages are random. Even the sheet music. In fact, I don’t read music. I look at printed music as calligraphy, as beautiful details. I do not smoke Gauloise cigarettes, but that particular blue of the label happens to attract me, so I possess it. Moreover, the collages are a kind of private diary—a privately coded diary, not made with an actual autobiographical intention. … For a painter as abstract as myself, the collages offer a way of incorporating bits of the everyday world into my pictures.” [2]

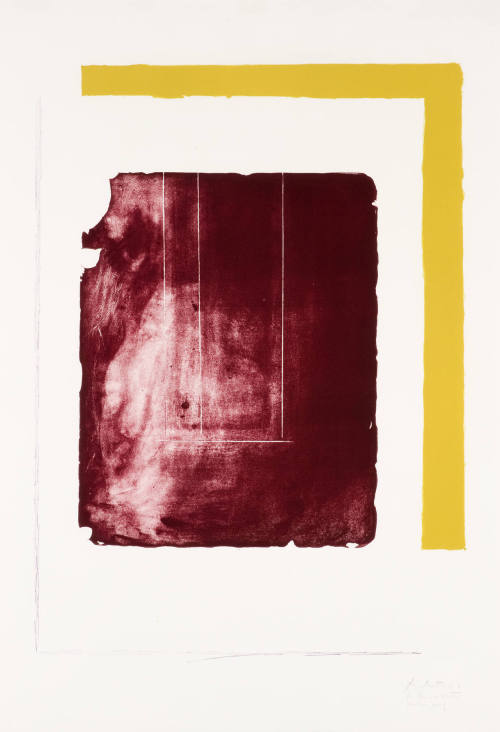

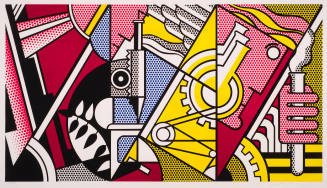

Motherwell’s skill with printmaking is also noteworthy. He initially worked with etching under the guidance of Kurt Seligmann in the early 1940s, and was one of the first to be invited by Tatyana Grosman to work in lithography at Universal Limited Art Editions. Initially, he was reluctant to tackle the litho stones provided by Grosman, but soon he came to appreciate the collaboration and input from her and her master printers. Eventually, he became so enthusiastic about printmaking that he worked with other shops including Gemini G.E.L. and Tyler Graphics, and, in 1972, he hired his own master printer. “I had always loved working on paper, but it was the camaraderie of the artist-printer relationship that tilted the scale definitively.” [3]

With his background in philosophy and his facility with words, it was natural for Motherwell to serve as spokesperson for the Abstract Expressionists. He lectured extensively, taught at Hunter College in New York, and wrote articles, such as “What Abstract Art Means to Me,” a kind of personal manifesto. He starts with: “The emergence of abstract art is one sign that there are still men able to assert feelings in the world. Men who know how to respect and follow their inner feelings.” He then continues with a quasi-definition of abstract art: “One of the most striking aspects of abstract art’s appearance is her nakedness, an art stripped bare. How many rejections on the part of her artists! Whole worlds—the world of objects, the world of power and propaganda, the world of anecdotes, the world of fetishes and ancestor worship. One might almost legitimately receive the impression that abstract artists don’t like anything but the act of painting.” [4]

Notes:

[1] Motherwell, “A Conversation at Lunch,” An Exhibition of the Work of Robert Motherwell (Northampton, MA: Smith College Museum of Art, 1963), unpaginated, quoted in Jack Flam, “With Robert Motherwell,” Robert Motherwell (New York: Abbeville Press in association with the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1983), 10, and Motherwell quoted in David Sylvester, “Painting as Existence: An Interview with Robert Motherwell,” Metro 7 (1962), 95, quoted in Dore Ashton, ed., The Writings of Robert Motherwell (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007), 207.

[2] Motherwell quoted in Flam, “With Robert Motherwell,” 16.

[3] Motherwell quoted in Jack Flam, “A Special Genius: Robert Motherwell’s Graphics,” Tyler Graphics: The Extended Image, Exhibition catalogue (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1987), 52, quoted in Siri Engberg, Robert Motherwell: The Complete Prints, 1940–1991, Catalogue Raisonné (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2003), 19.

[4] Motherwell, “What Abstract Art Means to Me,” Museum of Modern Art Bulletin18, no. 3 (Spring 1951), 12–13, quoted in Ashton, ed., The Writings of Robert Motherwell, 159.

Robert Motherwell

1915 - 1991

A product of the American West who figured prominently in the New York art world, Motherwell was born in Aberdeen, Washington, and spent parts of his childhood in California and Utah. After studying at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco for a year, he attended Stanford University, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy in 1937. Subsequently, for a year, he continued to study philosophy at the Graduate School of the Arts and Sciences at Harvard University. In 1939, he moved to New York, where Columbia University professor Meyer Shapiro introduced him to some of the European Surrealists who were living in exile. After experimenting with automatic drawings, he began making collages, which were shown at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in 1944.

New York in the 1940s was a vibrant place, and Motherwell began to interact with other artists working abstractedly and on a large scale. He became friendly with Mark Rothko, William Baziotes, and, in particular, the sculptor David Smith. During the summer of 1945, he taught at Black Mountain College, near Asheville, North Carolina. He made several trips to Mexico and became enamored with Spanish culture and history and, in 1948, embarked on his signature series, entitled Elegy to the Spanish Republic. Ominous black forms, which are metaphors for the strife and suffering of the times, dominate these large canvases. Unlike his fellow Abstract Expressionists, however, there is content in Motherwell’s art—not narrative or anecdotal—but art that is endowed with meaning. To him, “Black is death; white is life, éclat.” Other series, like Je t’aime with its bold calligraphy across canvases, unabashedly violate abstraction. In an interview, he explained: “Yes, painting is exactly a metaphor for reality. I do think there are references. I think the so-called ‘abstractness’ of modern art is not that it is about things, but that it’s an art really in the tradition of French Symbolist poetry, which is to say, an art that refuses to spell everything out. It’s a kind of shorthand, where a great deal is assumed.” [1]

For Motherwell, collage making was a release from large abstract painting as well as an indulgence in spontaneity. “Most of the papers I use in my collages are random. Even the sheet music. In fact, I don’t read music. I look at printed music as calligraphy, as beautiful details. I do not smoke Gauloise cigarettes, but that particular blue of the label happens to attract me, so I possess it. Moreover, the collages are a kind of private diary—a privately coded diary, not made with an actual autobiographical intention. … For a painter as abstract as myself, the collages offer a way of incorporating bits of the everyday world into my pictures.” [2]

Motherwell’s skill with printmaking is also noteworthy. He initially worked with etching under the guidance of Kurt Seligmann in the early 1940s, and was one of the first to be invited by Tatyana Grosman to work in lithography at Universal Limited Art Editions. Initially, he was reluctant to tackle the litho stones provided by Grosman, but soon he came to appreciate the collaboration and input from her and her master printers. Eventually, he became so enthusiastic about printmaking that he worked with other shops including Gemini G.E.L. and Tyler Graphics, and, in 1972, he hired his own master printer. “I had always loved working on paper, but it was the camaraderie of the artist-printer relationship that tilted the scale definitively.” [3]

With his background in philosophy and his facility with words, it was natural for Motherwell to serve as spokesperson for the Abstract Expressionists. He lectured extensively, taught at Hunter College in New York, and wrote articles, such as “What Abstract Art Means to Me,” a kind of personal manifesto. He starts with: “The emergence of abstract art is one sign that there are still men able to assert feelings in the world. Men who know how to respect and follow their inner feelings.” He then continues with a quasi-definition of abstract art: “One of the most striking aspects of abstract art’s appearance is her nakedness, an art stripped bare. How many rejections on the part of her artists! Whole worlds—the world of objects, the world of power and propaganda, the world of anecdotes, the world of fetishes and ancestor worship. One might almost legitimately receive the impression that abstract artists don’t like anything but the act of painting.” [4]

Notes:

[1] Motherwell, “A Conversation at Lunch,” An Exhibition of the Work of Robert Motherwell (Northampton, MA: Smith College Museum of Art, 1963), unpaginated, quoted in Jack Flam, “With Robert Motherwell,” Robert Motherwell (New York: Abbeville Press in association with the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1983), 10, and Motherwell quoted in David Sylvester, “Painting as Existence: An Interview with Robert Motherwell,” Metro 7 (1962), 95, quoted in Dore Ashton, ed., The Writings of Robert Motherwell (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007), 207.

[2] Motherwell quoted in Flam, “With Robert Motherwell,” 16.

[3] Motherwell quoted in Jack Flam, “A Special Genius: Robert Motherwell’s Graphics,” Tyler Graphics: The Extended Image, Exhibition catalogue (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1987), 52, quoted in Siri Engberg, Robert Motherwell: The Complete Prints, 1940–1991, Catalogue Raisonné (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2003), 19.

[4] Motherwell, “What Abstract Art Means to Me,” Museum of Modern Art Bulletin18, no. 3 (Spring 1951), 12–13, quoted in Ashton, ed., The Writings of Robert Motherwell, 159.

Person TypeIndividual