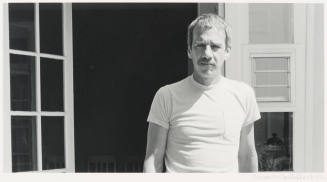

Skip to main contentBiographyFormally trained as a painter, David Smith (1906–1965) emerged as the premier sculptor of the abstract expressionist era, and, like the painters, he worked on a large scale and was innovative in his technique. Even critic Clement Greenberg, champion of the abstract expressionists, hailed Smith as potentially this country’s greatest sculptor, saluting the work’s “unevenness, its scrawl, in all its bewildering diversity… [which] somehow remains open, unfinished.” [1] Thematically, however, Smith’s work was rooted in the human figure and landscape, and stylistically he was indebted to Cubism, Surrealism, and Constructivism.

Smith was born in Decatur, Indiana, and moved as a teenager to Paulding, Ohio. Some of his forebears served as models for his ingenuity: his great-grandfather was a blacksmith, and his father was a telephone engineer and amateur inventor. Smith attended Ohio University in Athens for one year, and left the University of Notre Dame after two weeks because they offered no art courses. In South Bend, Indiana, he was employed at a Studebaker automobile factory where he learned welding and riveting. In 1927, he moved to New York and, until 1932, he studied at the Art Students League where he met, and later married, fellow artist Dorothy Dehner. He became friendly with John Graham, Stuart Davis, Arshile Gorky, and Willem de Kooning. Graham is credited with introducing Smith to sculptures by Pablo Picasso and Julio Gonzalez, two critical influences on his work. In 1933, he began to rent space at Terminal Iron Works in Brooklyn and seven years later he moved his studio and residence to rural Bolton Landing on Lake George in upstate New York.

During World War II, to avoid the draft, Smith worked in a locomotive and tank factory, and did little of his own work because most metals were in short supply. In the late forties, Smith taught at Sarah Lawrence College, in Bronxville, New York, and in 1950 and 1951, he benefited from two Solomon R. Guggenheim fellowships, which freed him to concentrate on his sculptures. He began to exhibit regularly at New York galleries, and had works purchased by the Whitney Museum of American Art and The Museum of Modern Art, which mounted a retrospective exhibition in 1957. Five years later, he was selected to participate in the Festival of the Two Worlds in Spoleto, Italy, and, using an abandoned welding factory in nearby Voltri, he made twenty-seven sculptures in thirty days. They were displayed in the narrow streets and Roman amphitheater of the old hilltown.

Smith once declared in an interview: “there is no such thing as truly abstract. Man always has to work from his life." His early expressive figurative sculptures subscribe to this theory. He developed “line sculptures”—meant to be read from each side, not in the round, and heavily dependent on the interaction of positive and negative shapes. Many of his freestanding pieces are reminiscent of totems, with one shape piled upon another. Collage and assemblage were important to Smith, and he frequently combined found objects alongside forms he had created. In the 1930s, he developed an interest in organic Surrealism, which was followed by his late geometric constructions. It was in these last works, with their burnished and articulated surfaces, that Smith came closest to the abstract expressionists. His methodology also resembled their intuitive approach: “When I begin a sculpture I am not always sure how it is going to end. In a way it has a relationship to the work before, it is in continuity to this previous work—it often holds a promise or a gesture towards the one to follow.” [2]

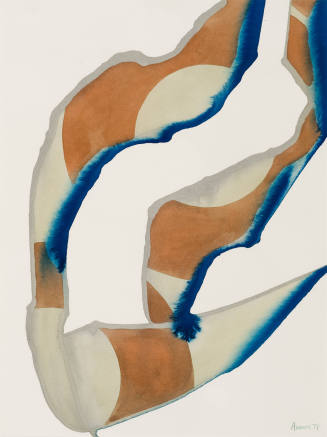

Prior to the twentieth century, most sculpture had been carved or cast. By consistently working in iron and steel that was welded together, Smith broke new ground. While he is best known for his steel assemblages, he also mastered several sculptural and drawing techniques that employed various media including bronze, wood, and ink with egg yolk. He drew human figures virtually every day, creating a prodigious number of drawings, which are filled with organic shapes reminiscent of his friend Gorky. He lectured about the importance of methodology and technique and wrote several articles about his various working processes. Nevertheless, Smith recognized that technical proficiency was only one component of great art; he indicated, “A certain feeling for form will develop with technical skill, but imaginative form or aesthetic vision is not a guarantee for high technique.” [3]

At Bolton Landing, he located his work in the rolling fields that surrounded his house and studio. His good friend, abstract expressionist Robert Motherwell, enthused about Smith’s “sculpture farm,” saying, “When I saw David place his work against the mountains and the sky, the impulse was plain, an ineffable desire to see his humanness related to exterior reality, to nature at least if not man, for the marvel of the felt scale that exists between a true work and the immovable world, the relation that makes both human.” [4]

Notes:

[1] Greenberg, “David Smith. Critical Comment,” Art in America 54 (January–February 1966), 27–32, quoted in Cleve Gray, ed. David Smith by David Smith (New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston, 1968), 8.

[2] Smith, interview with David Sylvester, 1964, quoted in Garnett McCoy, David Smith (New York: Praeger, 1973), 171, and Smith, notebook, 1952–1959, Archives of American Art, roll 4, quoted in Gray, ed. David Smith, 8.

[3] Smith, notebook, Archives of American Art, roll 4, quoted in Gray, ed. David Smith, 52.

[4] Motherwell, For David Smith. Exhibition catalogue. (New York: Willard Gallery, 1950), quoted in Gray, ed. David Smith, 8.

David Smith

1906 - 1965

Smith was born in Decatur, Indiana, and moved as a teenager to Paulding, Ohio. Some of his forebears served as models for his ingenuity: his great-grandfather was a blacksmith, and his father was a telephone engineer and amateur inventor. Smith attended Ohio University in Athens for one year, and left the University of Notre Dame after two weeks because they offered no art courses. In South Bend, Indiana, he was employed at a Studebaker automobile factory where he learned welding and riveting. In 1927, he moved to New York and, until 1932, he studied at the Art Students League where he met, and later married, fellow artist Dorothy Dehner. He became friendly with John Graham, Stuart Davis, Arshile Gorky, and Willem de Kooning. Graham is credited with introducing Smith to sculptures by Pablo Picasso and Julio Gonzalez, two critical influences on his work. In 1933, he began to rent space at Terminal Iron Works in Brooklyn and seven years later he moved his studio and residence to rural Bolton Landing on Lake George in upstate New York.

During World War II, to avoid the draft, Smith worked in a locomotive and tank factory, and did little of his own work because most metals were in short supply. In the late forties, Smith taught at Sarah Lawrence College, in Bronxville, New York, and in 1950 and 1951, he benefited from two Solomon R. Guggenheim fellowships, which freed him to concentrate on his sculptures. He began to exhibit regularly at New York galleries, and had works purchased by the Whitney Museum of American Art and The Museum of Modern Art, which mounted a retrospective exhibition in 1957. Five years later, he was selected to participate in the Festival of the Two Worlds in Spoleto, Italy, and, using an abandoned welding factory in nearby Voltri, he made twenty-seven sculptures in thirty days. They were displayed in the narrow streets and Roman amphitheater of the old hilltown.

Smith once declared in an interview: “there is no such thing as truly abstract. Man always has to work from his life." His early expressive figurative sculptures subscribe to this theory. He developed “line sculptures”—meant to be read from each side, not in the round, and heavily dependent on the interaction of positive and negative shapes. Many of his freestanding pieces are reminiscent of totems, with one shape piled upon another. Collage and assemblage were important to Smith, and he frequently combined found objects alongside forms he had created. In the 1930s, he developed an interest in organic Surrealism, which was followed by his late geometric constructions. It was in these last works, with their burnished and articulated surfaces, that Smith came closest to the abstract expressionists. His methodology also resembled their intuitive approach: “When I begin a sculpture I am not always sure how it is going to end. In a way it has a relationship to the work before, it is in continuity to this previous work—it often holds a promise or a gesture towards the one to follow.” [2]

Prior to the twentieth century, most sculpture had been carved or cast. By consistently working in iron and steel that was welded together, Smith broke new ground. While he is best known for his steel assemblages, he also mastered several sculptural and drawing techniques that employed various media including bronze, wood, and ink with egg yolk. He drew human figures virtually every day, creating a prodigious number of drawings, which are filled with organic shapes reminiscent of his friend Gorky. He lectured about the importance of methodology and technique and wrote several articles about his various working processes. Nevertheless, Smith recognized that technical proficiency was only one component of great art; he indicated, “A certain feeling for form will develop with technical skill, but imaginative form or aesthetic vision is not a guarantee for high technique.” [3]

At Bolton Landing, he located his work in the rolling fields that surrounded his house and studio. His good friend, abstract expressionist Robert Motherwell, enthused about Smith’s “sculpture farm,” saying, “When I saw David place his work against the mountains and the sky, the impulse was plain, an ineffable desire to see his humanness related to exterior reality, to nature at least if not man, for the marvel of the felt scale that exists between a true work and the immovable world, the relation that makes both human.” [4]

Notes:

[1] Greenberg, “David Smith. Critical Comment,” Art in America 54 (January–February 1966), 27–32, quoted in Cleve Gray, ed. David Smith by David Smith (New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston, 1968), 8.

[2] Smith, interview with David Sylvester, 1964, quoted in Garnett McCoy, David Smith (New York: Praeger, 1973), 171, and Smith, notebook, 1952–1959, Archives of American Art, roll 4, quoted in Gray, ed. David Smith, 8.

[3] Smith, notebook, Archives of American Art, roll 4, quoted in Gray, ed. David Smith, 52.

[4] Motherwell, For David Smith. Exhibition catalogue. (New York: Willard Gallery, 1950), quoted in Gray, ed. David Smith, 8.

Person TypeIndividual