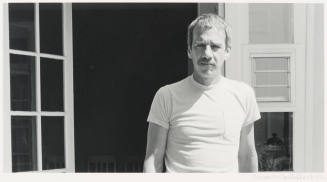

Skip to main contentBiographyIndividuals who are truly interdisciplinary and cross-cultural are rare; they seek to find the unifying threads that weave through various forms of human expression and across ethnic boundaries. They often operate outside the normal framework of society and live eccentric lifestyles. The multifaceted Harry Smith (1923–1991)—anthropologist, filmmaker, musicologist, and artist—was a supreme example of this phenomenon.

Smith was born in Portland, Oregon, but spent his early years in small rural towns in the Seattle, Washington area. His parents were theosophists and held pantheistic beliefs. Their unorthodox positions clearly influenced their son, who recalled, “When I was a child there were a great many books on occultism and alchemy always in the basement. Like I say, my father gave me a blacksmith shop when I was maybe twelve. He told me I should convert lead into gold. … I once discovered in the attic of our house all those illuminated documents with hands and eyes in them, all kinds of Masonic deals that belonged to my grandfather. … That was the background for my interest in metaphysics and so forth.” His mother taught school on a Lummi Indian Reservation, which led to his interest in Native Americans, an interest furthered when “somebody came to school one day and said they’d been to an Indian dance, and they saw somebody swinging a skull on the end of a string, so I thought, ‘Hmm, I have to see this.’” [1]

While still in high school, Smith avidly collected 78rpm records encompassing a great variety of musical styles, with an emphasis on folk renditions. Simultaneously, he began to document Native American songs and rituals and to collect artifacts that he ultimately gave to the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Washington. Among the items he owned were a smoking pipe, a canoe bailer, house posts, funerary figurines, and string figures, many of which were repatriated to descendants in compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

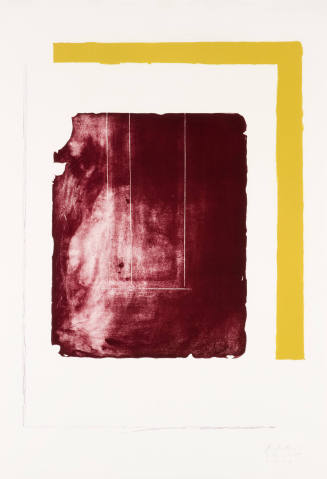

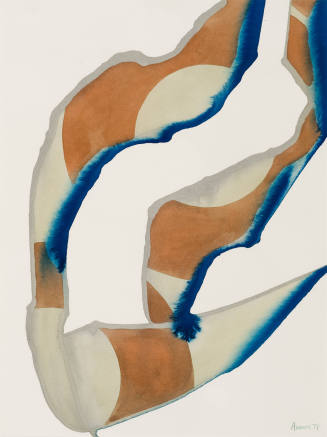

After high school, Smith received a medical exemption from military service and attended the University of Washington for five semesters, studying such subjects as geology, principles of race and language, and American indigenous linguistics. The day after World War II ended, he went to San Francisco, where two early experiences served to shape his future: a Woody Guthrie concert and marijuana. He soon moved to Berkeley where he enjoyed a bohemian lifestyle and became an active volunteer at Art in Cinema, a series of avant-garde films screened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. With this exposure to experimental cinema, Smith began to make and present his own films, which were usually non-narrative, abstract, and often hand-painted. In addition, he created paintings that were colorful visualizations of music filled with intersecting and layered orbs and circles.

Smith sought and received financial support for his filmmaking from Hilla Rebay, the first director of Solomon R. Guggenheim’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting. He sent her a sample of his films and several paintings which resemble the work of Wassily Kandinsky and Rudolf Bauer, who were well represented in the collection she oversaw. In 1951, he moved to New York City, so that he could see Rebay, meet Marcel Duchamp, and hear jazz at Birdland. The following year, using his extensive record collection, he produced Anthology of American Folk Music, a groundbreaking study which influenced such performers as Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. He explained his choices: “The Anthology was not an attempt to get all the best records. … but a lot of these were selected because they were odd—an important version of the song, one which came from some particular place. … Instead, they were selected to be ones that would be popular among musicologists, or possibly with people who want to sing them and maybe improve the version. … I was looking for exotic records.”[2]

For the next few decades Smith poured his considerable energies into his films and paintings, which tend to reflect his interest in magic, cosmology, and metaphysics. One project of the 1960s was Oz, a feature-length film based on L. Frank Baum’s famous tale. According to Smith, “It was to be a commercial film. Very elaborate equipment was built. … I ditched the Munchkins, Quadlings, Gillikins and Winkies in their original form. What I was really trying to do was to convert Oz into a Buddhistic image like a mandala.” When funding dried up, Smith was forced to abandon the endeavor. Another monumental undertaking was a film interpretation of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s, Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, which he described “as intelligible to the Zulu, Eskimo, or the Australian Aborigine, as to people of any other cultural background or age.” [3] After years of labor, it debuted in 1980 at the Anthology Film Archives in New York.

Smith’s lifestyle was as eccentric as his projects. Surrounded by his various collections of paper airplanes, Seminole textiles, and Ukrainian Easter eggs, he lived mostly at the legendary Chelsea Hotel, known its unconventional residents and drug scene. He spent hours at the New York Public Library tracing books and documents on occult religions and alchemy. In a period of destitution toward the end of his life, he lived with beat poet Allen Ginsberg, a friend since 1960, who arranged for Smith to be “shaman in residence” at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado. Ginsberg’s poem Howl is a graphic description of bohemian existence; its first line could serve as a reference to Harry Smith:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked….

Smith died at the Chelsea Hotel in 1991.

Notes:

[1] Smith interview with P. Adams Sitney, “P. Adams Sitney—NYC,” Film Culture 37, no. 16, 1965, quoted in Rani Singh, ed. Think of the Self-Speaking Harry Smith—Selected Interviews (Seattle, WA: Elbow/Cityful, 1999), 47–48.

[2] Smith interview with John Cohen, “John Cohen—Chelsea Hotel, NYC,” Sing Out!19, no. 1, 1969, quoted in Singh, ed. Think of the Self-Speaking Harry Smith , 68–70.

[3] Smith interview with P. Adams Sitney, 60, and Smith to the Committee on Poetry, grant application typescript, Harry Smith Archives, quoted in Andrew Perchuk and Rani Singh, ed., Harry Smith: The Avant-Garde in the American Vernacular (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute, 2010), 41.

Harry Smith

1923 - 1991

Smith was born in Portland, Oregon, but spent his early years in small rural towns in the Seattle, Washington area. His parents were theosophists and held pantheistic beliefs. Their unorthodox positions clearly influenced their son, who recalled, “When I was a child there were a great many books on occultism and alchemy always in the basement. Like I say, my father gave me a blacksmith shop when I was maybe twelve. He told me I should convert lead into gold. … I once discovered in the attic of our house all those illuminated documents with hands and eyes in them, all kinds of Masonic deals that belonged to my grandfather. … That was the background for my interest in metaphysics and so forth.” His mother taught school on a Lummi Indian Reservation, which led to his interest in Native Americans, an interest furthered when “somebody came to school one day and said they’d been to an Indian dance, and they saw somebody swinging a skull on the end of a string, so I thought, ‘Hmm, I have to see this.’” [1]

While still in high school, Smith avidly collected 78rpm records encompassing a great variety of musical styles, with an emphasis on folk renditions. Simultaneously, he began to document Native American songs and rituals and to collect artifacts that he ultimately gave to the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Washington. Among the items he owned were a smoking pipe, a canoe bailer, house posts, funerary figurines, and string figures, many of which were repatriated to descendants in compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

After high school, Smith received a medical exemption from military service and attended the University of Washington for five semesters, studying such subjects as geology, principles of race and language, and American indigenous linguistics. The day after World War II ended, he went to San Francisco, where two early experiences served to shape his future: a Woody Guthrie concert and marijuana. He soon moved to Berkeley where he enjoyed a bohemian lifestyle and became an active volunteer at Art in Cinema, a series of avant-garde films screened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. With this exposure to experimental cinema, Smith began to make and present his own films, which were usually non-narrative, abstract, and often hand-painted. In addition, he created paintings that were colorful visualizations of music filled with intersecting and layered orbs and circles.

Smith sought and received financial support for his filmmaking from Hilla Rebay, the first director of Solomon R. Guggenheim’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting. He sent her a sample of his films and several paintings which resemble the work of Wassily Kandinsky and Rudolf Bauer, who were well represented in the collection she oversaw. In 1951, he moved to New York City, so that he could see Rebay, meet Marcel Duchamp, and hear jazz at Birdland. The following year, using his extensive record collection, he produced Anthology of American Folk Music, a groundbreaking study which influenced such performers as Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. He explained his choices: “The Anthology was not an attempt to get all the best records. … but a lot of these were selected because they were odd—an important version of the song, one which came from some particular place. … Instead, they were selected to be ones that would be popular among musicologists, or possibly with people who want to sing them and maybe improve the version. … I was looking for exotic records.”[2]

For the next few decades Smith poured his considerable energies into his films and paintings, which tend to reflect his interest in magic, cosmology, and metaphysics. One project of the 1960s was Oz, a feature-length film based on L. Frank Baum’s famous tale. According to Smith, “It was to be a commercial film. Very elaborate equipment was built. … I ditched the Munchkins, Quadlings, Gillikins and Winkies in their original form. What I was really trying to do was to convert Oz into a Buddhistic image like a mandala.” When funding dried up, Smith was forced to abandon the endeavor. Another monumental undertaking was a film interpretation of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s, Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, which he described “as intelligible to the Zulu, Eskimo, or the Australian Aborigine, as to people of any other cultural background or age.” [3] After years of labor, it debuted in 1980 at the Anthology Film Archives in New York.

Smith’s lifestyle was as eccentric as his projects. Surrounded by his various collections of paper airplanes, Seminole textiles, and Ukrainian Easter eggs, he lived mostly at the legendary Chelsea Hotel, known its unconventional residents and drug scene. He spent hours at the New York Public Library tracing books and documents on occult religions and alchemy. In a period of destitution toward the end of his life, he lived with beat poet Allen Ginsberg, a friend since 1960, who arranged for Smith to be “shaman in residence” at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado. Ginsberg’s poem Howl is a graphic description of bohemian existence; its first line could serve as a reference to Harry Smith:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked….

Smith died at the Chelsea Hotel in 1991.

Notes:

[1] Smith interview with P. Adams Sitney, “P. Adams Sitney—NYC,” Film Culture 37, no. 16, 1965, quoted in Rani Singh, ed. Think of the Self-Speaking Harry Smith—Selected Interviews (Seattle, WA: Elbow/Cityful, 1999), 47–48.

[2] Smith interview with John Cohen, “John Cohen—Chelsea Hotel, NYC,” Sing Out!19, no. 1, 1969, quoted in Singh, ed. Think of the Self-Speaking Harry Smith , 68–70.

[3] Smith interview with P. Adams Sitney, 60, and Smith to the Committee on Poetry, grant application typescript, Harry Smith Archives, quoted in Andrew Perchuk and Rani Singh, ed., Harry Smith: The Avant-Garde in the American Vernacular (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Research Institute, 2010), 41.

Person TypeIndividual