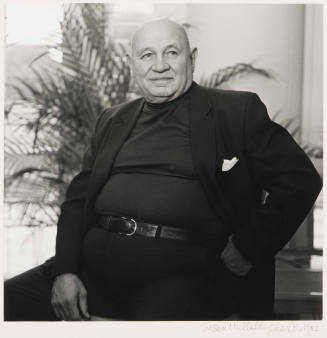

Skip to main contentBiographyThroughout the history of art, artists used their creative energy to change the political status quo. In the nineteenth century, Francisco Goya and Honoré Daumier used their art to rail against the injustices directed at the disenfranchised. In the twentieth century, many artists, including Rudolf Baranik (1920–1998), rallied together to protest the Vietnam War. But, as a self-described “social formalist,” he did not always make art that overtly reflected his political views.

Baranik was born in Anykšciai, Lithuania. His parents were Jewish socialists who encouraged his early interest in art. Increasing concern about the political situation in Lithuania led Rudolf, in 1938, to immigrate to the United States. With the help of a wealthy uncle, he settled in Chicago, but his socialist views soon alienated his conservative relative. He moved out, worked at a Lithuanian newspaper, and attended classes at progressive-leaning Roosevelt College. In 1942, Baranik enlisted in the army and was stationed for a year in England, then in Germany for the rest of World War II. Upon his return to the States in 1946, he continued his studies at the Art Institute of Chicago and then moved to New York to study at the Art Students League, where he met and married the feminist and fellow artist May Stevens.

With a stipend from the G.I. Bill, Baranik and Stevens went to Paris where they enrolled at the historic Académie Julien. Baranik also studied with Fernand Léger at the Académie Léger. While in France, both Stevens and Baranik had works included in important exhibitions, and, in 1951, he had his first one-man show. When funds from the G.I. Bill expired, they left Paris for New York. He joined the ACA Gallery, whose artists included such social realists as Philip Evergood, Robert Gwathmey, and Jacob Lawrence.

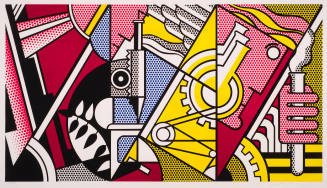

Still a socialist, Baranik began to meet some of the Abstract Expressionists and became friends with Ad Reinhardt. He was included in the 1958 Whitney Annual and, by 1960, was exhibiting widely. During the following decade, he and Stevens became increasingly involved in protesting the war in Vietnam. In 1967, they, along with art historians Dore Ashton and Barbara Rose, artist Leon Golub, and others, formed a committee to organize anti-war Happenings that became known as the Angry Arts. Baranik’s art became more specifically critical of the war as exemplified by his most important series from the late 1960s and 1970s, The Napalm Elegies. His continued commitment to political activism meant that he fell out of the art mainstream in terms of critical attention and exhibition opportunities. His work from this time also included Collages, in which he used photostatic images from various sources in popular media to create elegiac landscapes.

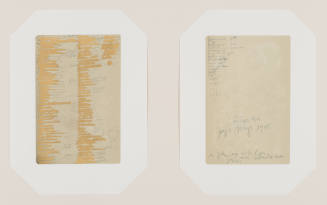

In 1981, Baranik was shaken by the suicide of his son; his grief at this loss is reflected in two early 1980s series titled Words and Edge Manifestoes. He described these works: “I wrote long line after long line across the black field, stepping back to evaluate each line for its holistic pulsation while at the same time repeating to myself the lines of poetry I was putting down, often interspersed with long letters to my son. I was not inclined to explain what these works meant to me but there also was not need for it: the work seemed to be understood.” [1]

In his obituary in The New York Times, critic Roberta Smith stated: “Mr. Baranik believed equally in art’s ‘poetic prerogatives’ and its ‘moral responsibility,’ a stance that made him a moderating, unusually flexible anomaly in the polemic-prone art world of the 1970s and 80s. At a time when art and politics were often seen as an either/or choice, Mr. Baranik defended painting’s sovereignty against those who thought it was dead or irrelevant and argued for its social role against those who thought it should remain above the political fray.” [2]

Notes:

[1] Baranik, “Biographical Notes,” Rudolf Baranik Elegies: Sleep—Napalm —Night Sky (Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Gallery of Fine Art, 1987), 84.

[2] Smith, Roberta. “Rudolf Baranik Dies at 77; Artist and a Political Force,” The New York Times, March 15, 1998.

Rudolf Baranik

1920 - 1998

Baranik was born in Anykšciai, Lithuania. His parents were Jewish socialists who encouraged his early interest in art. Increasing concern about the political situation in Lithuania led Rudolf, in 1938, to immigrate to the United States. With the help of a wealthy uncle, he settled in Chicago, but his socialist views soon alienated his conservative relative. He moved out, worked at a Lithuanian newspaper, and attended classes at progressive-leaning Roosevelt College. In 1942, Baranik enlisted in the army and was stationed for a year in England, then in Germany for the rest of World War II. Upon his return to the States in 1946, he continued his studies at the Art Institute of Chicago and then moved to New York to study at the Art Students League, where he met and married the feminist and fellow artist May Stevens.

With a stipend from the G.I. Bill, Baranik and Stevens went to Paris where they enrolled at the historic Académie Julien. Baranik also studied with Fernand Léger at the Académie Léger. While in France, both Stevens and Baranik had works included in important exhibitions, and, in 1951, he had his first one-man show. When funds from the G.I. Bill expired, they left Paris for New York. He joined the ACA Gallery, whose artists included such social realists as Philip Evergood, Robert Gwathmey, and Jacob Lawrence.

Still a socialist, Baranik began to meet some of the Abstract Expressionists and became friends with Ad Reinhardt. He was included in the 1958 Whitney Annual and, by 1960, was exhibiting widely. During the following decade, he and Stevens became increasingly involved in protesting the war in Vietnam. In 1967, they, along with art historians Dore Ashton and Barbara Rose, artist Leon Golub, and others, formed a committee to organize anti-war Happenings that became known as the Angry Arts. Baranik’s art became more specifically critical of the war as exemplified by his most important series from the late 1960s and 1970s, The Napalm Elegies. His continued commitment to political activism meant that he fell out of the art mainstream in terms of critical attention and exhibition opportunities. His work from this time also included Collages, in which he used photostatic images from various sources in popular media to create elegiac landscapes.

In 1981, Baranik was shaken by the suicide of his son; his grief at this loss is reflected in two early 1980s series titled Words and Edge Manifestoes. He described these works: “I wrote long line after long line across the black field, stepping back to evaluate each line for its holistic pulsation while at the same time repeating to myself the lines of poetry I was putting down, often interspersed with long letters to my son. I was not inclined to explain what these works meant to me but there also was not need for it: the work seemed to be understood.” [1]

In his obituary in The New York Times, critic Roberta Smith stated: “Mr. Baranik believed equally in art’s ‘poetic prerogatives’ and its ‘moral responsibility,’ a stance that made him a moderating, unusually flexible anomaly in the polemic-prone art world of the 1970s and 80s. At a time when art and politics were often seen as an either/or choice, Mr. Baranik defended painting’s sovereignty against those who thought it was dead or irrelevant and argued for its social role against those who thought it should remain above the political fray.” [2]

Notes:

[1] Baranik, “Biographical Notes,” Rudolf Baranik Elegies: Sleep—Napalm —Night Sky (Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Gallery of Fine Art, 1987), 84.

[2] Smith, Roberta. “Rudolf Baranik Dies at 77; Artist and a Political Force,” The New York Times, March 15, 1998.

Person TypeIndividual