Skip to main contentBiographyCoincident with the Great Depression, an art movement variously called Regionalism or American Scene painting emerged that reacted against European modernism and celebrated the country’s heartland in a realistic style. Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975) formed a triumvirate that reassured audiences at a time of great upheaval; in doing so they garnered a great deal of criticism from the avant-garde art world.

Benton was born in Neosho, Missouri, to a wealthy and politically powerful family. His father served under Grover Cleveland as the United States attorney for the Western district of Missouri, and his great-uncle, also named Thomas Hart Benton, was one of the first two United States senators from the show-me state. Young Benton was influenced at an early age by socialist theories, which often played out in his work.

The artist was exposed to art as a child. He attended grade school in the Washington, DC, area, where art education was part of the regular curriculum. Benton’s first job, as a cartoonist for the Joplin American newspaper in Missouri, led him to pursue art more seriously. In 1907 he enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago. Soon afterwards he went to Paris where he studied from 1908 to 1909 at the Académie Julien. While abroad, the artist was favorably impressed by the work of Spanish painters, particularly El Greco, whose curvy silhouettes he emulated. The Mexican muralist Diego Rivera was also an important influence, inspiring Benton’s later mural projects as well as his political views about art for the masses. [1]

Upon his return to the United States, Benton supported himself primarily through commercial endeavors, with an occasional exhibition of his paintings. In 1918, he enlisted in the Navy and worked as a naval draftsman. It was during his military service that Benton began to develop a style rooted in American realism. Following the war, he taught at the Art Students League in New York from 1926 until 1935.

In the 1920s, Benton began work on a monumental project called the American Historical Epic, a series that depicted heroic, violent, and corrupt incidents in America’s history. Though he abandoned the project, Benton continued to explore the darker side of the nation’s history, often examining the destructive effects of technology and the machine. For the New School for Social Research he painted America Today, ten mural paintings now in the lobby of the Equitable Building in New York. They illustrate all aspects of American life, including dance halls, cowboys, steel workers, and hard-pressed farmers. In 1932, he completed a related series, Arts of Life in America, New Britain Museum of Art, and, three years later paintings for the Missouri State Capitol that were controversial for their portrayal of the seamier side of the state’s history. Because of his success with murals and easel paintings, he was one of a very few Depression-era artists who did not receive funding through the government-supported Works Progress Administration. [2]

When Benton moved from New York to Missouri in 1935 to teach at the Kansas City Art Institute, it caused a rift between him and other politically minded artists; they saw his departure as an abandonment of their radical cause. [3] Despite this rejection by his peers, Benton prospered; he taught, lectured, and continued to paint until his death of a heart attack in 1975.

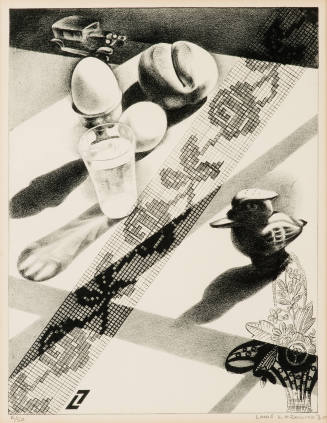

In his murals, oil paintings, lithographs, and illustrations, the artist imbued his subjects with an organic sense of movement that brings stereotypical figures and familiar characters to life. Over the course of his career, Benton developed a unique working method; he would research for months, create a clay model of the scene, and then paint his subject. The subsequent paintings have a plasticity that recalls mannerist art. Benton experienced a tumultuous relationship with critics and his contemporaries in the American art world. Despite detractors who saw his work as escapist, isolationist, and nationalistic, Benton maintained his unique style and narrative perspective, and his position as an American master has endured.

Notes:

[1] Benton, An Artist in America (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1968), 378–9.

[2] Elizabeth Broun, “Thomas Hart Benton: A Politician in Art,” in Smithsonian Studies in American Art Spring 1987, 59.

[3] Charles C. Eldredge, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, and Robert G. Workman, American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House, Museum of American Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990), 110.

Thomas Hart Benton

1889 - 1975

Benton was born in Neosho, Missouri, to a wealthy and politically powerful family. His father served under Grover Cleveland as the United States attorney for the Western district of Missouri, and his great-uncle, also named Thomas Hart Benton, was one of the first two United States senators from the show-me state. Young Benton was influenced at an early age by socialist theories, which often played out in his work.

The artist was exposed to art as a child. He attended grade school in the Washington, DC, area, where art education was part of the regular curriculum. Benton’s first job, as a cartoonist for the Joplin American newspaper in Missouri, led him to pursue art more seriously. In 1907 he enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago. Soon afterwards he went to Paris where he studied from 1908 to 1909 at the Académie Julien. While abroad, the artist was favorably impressed by the work of Spanish painters, particularly El Greco, whose curvy silhouettes he emulated. The Mexican muralist Diego Rivera was also an important influence, inspiring Benton’s later mural projects as well as his political views about art for the masses. [1]

Upon his return to the United States, Benton supported himself primarily through commercial endeavors, with an occasional exhibition of his paintings. In 1918, he enlisted in the Navy and worked as a naval draftsman. It was during his military service that Benton began to develop a style rooted in American realism. Following the war, he taught at the Art Students League in New York from 1926 until 1935.

In the 1920s, Benton began work on a monumental project called the American Historical Epic, a series that depicted heroic, violent, and corrupt incidents in America’s history. Though he abandoned the project, Benton continued to explore the darker side of the nation’s history, often examining the destructive effects of technology and the machine. For the New School for Social Research he painted America Today, ten mural paintings now in the lobby of the Equitable Building in New York. They illustrate all aspects of American life, including dance halls, cowboys, steel workers, and hard-pressed farmers. In 1932, he completed a related series, Arts of Life in America, New Britain Museum of Art, and, three years later paintings for the Missouri State Capitol that were controversial for their portrayal of the seamier side of the state’s history. Because of his success with murals and easel paintings, he was one of a very few Depression-era artists who did not receive funding through the government-supported Works Progress Administration. [2]

When Benton moved from New York to Missouri in 1935 to teach at the Kansas City Art Institute, it caused a rift between him and other politically minded artists; they saw his departure as an abandonment of their radical cause. [3] Despite this rejection by his peers, Benton prospered; he taught, lectured, and continued to paint until his death of a heart attack in 1975.

In his murals, oil paintings, lithographs, and illustrations, the artist imbued his subjects with an organic sense of movement that brings stereotypical figures and familiar characters to life. Over the course of his career, Benton developed a unique working method; he would research for months, create a clay model of the scene, and then paint his subject. The subsequent paintings have a plasticity that recalls mannerist art. Benton experienced a tumultuous relationship with critics and his contemporaries in the American art world. Despite detractors who saw his work as escapist, isolationist, and nationalistic, Benton maintained his unique style and narrative perspective, and his position as an American master has endured.

Notes:

[1] Benton, An Artist in America (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1968), 378–9.

[2] Elizabeth Broun, “Thomas Hart Benton: A Politician in Art,” in Smithsonian Studies in American Art Spring 1987, 59.

[3] Charles C. Eldredge, Barbara Babcock Millhouse, and Robert G. Workman, American Originals: Selections from Reynolda House, Museum of American Art (New York: Abbeville Press, 1990), 110.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms