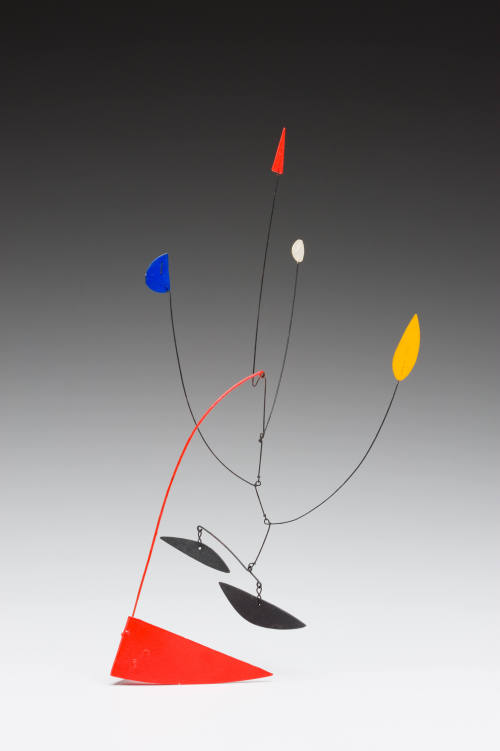

Skip to main contentBiographyAlexander Calder (1898–1976) was an iconic artist of the twentieth century, best known for his invention of hanging sculptures, dubbed “mobiles” by Marcel Duchamp in the 1930s. His whimsical sculptures, drawings, prints, and jewelry transmit a playful spirit using minimal and elegant forms. An artist-alchemist, he transformed inert industrial sheet metal and wire into organic living forms that capture and define space. Part of his success resulted from his attitude toward materials: “I feel an artist should go about his work simply with great respect for his materials…sculptors of all places and climates have used what came ready at hand.” [1]

Known as “Sandy” to his family and friends, Calder was born in Lawnton, Pennsylvania in 1898. His mother was a painter, and his father and grandfather were both accomplished sculptors. The family moved across the country, fielding commissions for sculpture in Arizona, California, and New York. As a young man, Calder enlisted in the Navy during the last months of World War I, then earned a degree in mechanical engineering from the Stevens Institute in Hoboken, New Jersey. For four years, he worked as an engineer, but then became interested in painting. In 1923 Calder enrolled in classes at the Art Students League in New York, where he studied with John Sloan and Thomas Hart Benton. Calder’s first artistic successes were his illustrations for the satirical paper, National Police Gazette, and a subsequent commission for a book titled Animal Sketching, 1926, that compiled pen and ink sketches of animals from the Bronx and Central Park zoos. [2]

Calder’s early accomplishments prompted him to further his studies abroad. He went to London, and then Paris, in the summer of 1926. While abroad, Calder first garnered attention for Cirque Calder, an assemblage of wire sculptures inspired by the artist’s love of the circus, because, as he explained, “I always loved the circus so I decided to make a circus just for the fun of it.” [3] While in France, Calder was influenced by the work of Joan Miró, Paul Klee, and Piet Mondrian. Their use of line and simple saturated palettes became hallmarks of Calder’s own artistic aesthetic, and he consistently incorporated these principles into his work.

In 1930, Calder made his first mobile, One Black Ball, One White Ball. His first endeavors were operated through mechanized parts, but soon he found ways to allow movement to become an integral and organic part of the sculpture without the use of cranks and pulleys. The development of the mobile as an art form launched Calder’s international success. Due to shortages of metal during World War II, he turned briefly to wood as a medium, but ultimately returned to his wire and sheet metal constructions. He casually described his methodology: “I start by cutting out a lot of shapes. Next I file them off. Some are bits I just happen to find. Then I arrange them on a table with wires between the pieces for the overall pattern. Finally I cut some more on them with my shears, calculating for balance this time.” [4]

While Calder is widely recognized as the father of the mobile, he was also responsible for the stabile, a stationary sculpture, usually painted his iconic red or black. Mobiles and stabiles became wildly popular and, as a result, Calder received numerous commissions for public places, including the National Gallery of Art’s East Wing and the plaza in front of Chicago’s Federal Plaza. His distinctive style is characterized by a memorable joie de vivre regardless of the scale of the work or its material.

Notes:

[1] Jean Lipman and Margaret Aspinwall, Alexander Calder and His Magical Mobiles (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc., in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1981), 44, and Calder, “Alexander Calder,” manuscript, 1943, Calder Foundation, New York, quoted in Jessica Holmes, Simplicity of Means: Calder and the Devised Object (New York: Jonathan O’Hara Gallery, 2007), 24.

[2] Daniel Marchesseau and Alexander Calder, The Intimate World of Alexander Calder. (Paris: S. Thierry, 1989), 359.

[3] Calder, quoted in Lipman and Aspinwall, Alexander Calder and His Magical Mobiles, 25.

[4] Ibid., 47–48.

Alexander Calder

1898 - 1976

Known as “Sandy” to his family and friends, Calder was born in Lawnton, Pennsylvania in 1898. His mother was a painter, and his father and grandfather were both accomplished sculptors. The family moved across the country, fielding commissions for sculpture in Arizona, California, and New York. As a young man, Calder enlisted in the Navy during the last months of World War I, then earned a degree in mechanical engineering from the Stevens Institute in Hoboken, New Jersey. For four years, he worked as an engineer, but then became interested in painting. In 1923 Calder enrolled in classes at the Art Students League in New York, where he studied with John Sloan and Thomas Hart Benton. Calder’s first artistic successes were his illustrations for the satirical paper, National Police Gazette, and a subsequent commission for a book titled Animal Sketching, 1926, that compiled pen and ink sketches of animals from the Bronx and Central Park zoos. [2]

Calder’s early accomplishments prompted him to further his studies abroad. He went to London, and then Paris, in the summer of 1926. While abroad, Calder first garnered attention for Cirque Calder, an assemblage of wire sculptures inspired by the artist’s love of the circus, because, as he explained, “I always loved the circus so I decided to make a circus just for the fun of it.” [3] While in France, Calder was influenced by the work of Joan Miró, Paul Klee, and Piet Mondrian. Their use of line and simple saturated palettes became hallmarks of Calder’s own artistic aesthetic, and he consistently incorporated these principles into his work.

In 1930, Calder made his first mobile, One Black Ball, One White Ball. His first endeavors were operated through mechanized parts, but soon he found ways to allow movement to become an integral and organic part of the sculpture without the use of cranks and pulleys. The development of the mobile as an art form launched Calder’s international success. Due to shortages of metal during World War II, he turned briefly to wood as a medium, but ultimately returned to his wire and sheet metal constructions. He casually described his methodology: “I start by cutting out a lot of shapes. Next I file them off. Some are bits I just happen to find. Then I arrange them on a table with wires between the pieces for the overall pattern. Finally I cut some more on them with my shears, calculating for balance this time.” [4]

While Calder is widely recognized as the father of the mobile, he was also responsible for the stabile, a stationary sculpture, usually painted his iconic red or black. Mobiles and stabiles became wildly popular and, as a result, Calder received numerous commissions for public places, including the National Gallery of Art’s East Wing and the plaza in front of Chicago’s Federal Plaza. His distinctive style is characterized by a memorable joie de vivre regardless of the scale of the work or its material.

Notes:

[1] Jean Lipman and Margaret Aspinwall, Alexander Calder and His Magical Mobiles (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc., in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1981), 44, and Calder, “Alexander Calder,” manuscript, 1943, Calder Foundation, New York, quoted in Jessica Holmes, Simplicity of Means: Calder and the Devised Object (New York: Jonathan O’Hara Gallery, 2007), 24.

[2] Daniel Marchesseau and Alexander Calder, The Intimate World of Alexander Calder. (Paris: S. Thierry, 1989), 359.

[3] Calder, quoted in Lipman and Aspinwall, Alexander Calder and His Magical Mobiles, 25.

[4] Ibid., 47–48.

Person TypeIndividual