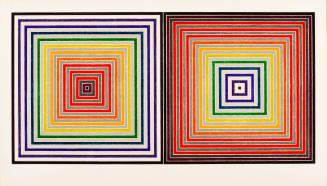

Skip to main contentBiography“Take an object, do something to it, do something else to it” has served as Jasper Johns’s guiding principle for most of his long and prolific career. Intrigued by such tangible things as flags and targets, symbols like numbers, and abstract motifs, Johns has revisited them over and over, in new combinations and in different media. "I like to repeat an image in another medium. … In a sense, one does the same thing two ways and can observe differences and sameness—the stress the image takes in different media. … I can understand that someone else might find that boring and repetitious, but that's not the way I see it." [1]

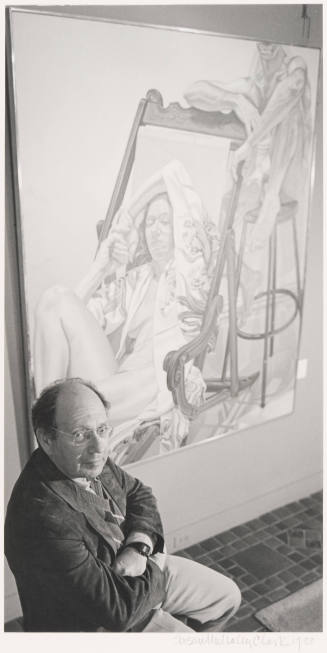

Always considered by himself and others to be a South Carolinian, Johns was born in Augusta, Georgia, in 1930, because the nearest hospital was located there. He spent his early childhood in rural Allendale, South Carolina, in the home of his paternal grandfather after the divorce of his parents. He also lived for a time with an aunt, and then with his mother and her new family. He studied mechanical drawing in high school in Sumter, where he was the class valedictorian, and attended the University of South Carolina for three semesters. At the urging of his art teachers, he moved to New York City in December 1948 at the age of eighteen.

In New York, Johns continued his studies at the Parsons School of Design and worked as a messenger boy and shipping clerk. His pursuit of art was interrupted by military service during the Korean War, first at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, then in Sendai, Japan. Discharged in 1953, he returned to New York, took a job at a bookstore, and visited exhibitions featuring Edvard Munch, Jackson Pollock, and Jacob Lawrence. After a few months he met Robert Rauschenberg, who, according to Johns, was “the first person I knew who was a real artist.” They began a close relationship that lasted six years, working together on windows for stores on Fifth Avenue, and occupying lofts near one another. Rauschenberg introduced Johns to the avant-garde dealer Leo Castelli, who would remain Johns’s representative for decades. [2]

Johns’s work was included in several important exhibitions, but his real breakthrough came with Flag, 1954–1955, an encaustic with collaged newspaper elements that startled the art world because of its overtly representational theme at a time when Abstract Expressionism was the dominant mode. This seminal piece was purchased, along with three others, for the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. All were encaustics, an ancient technique in which melted wax is the binder—a process Johns is credited with reviving.

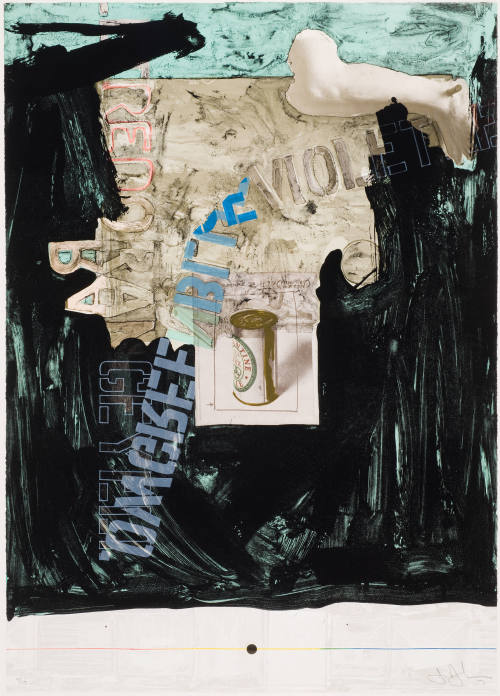

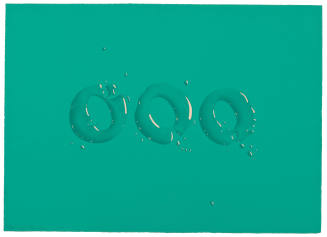

In 1960, Johns made his first print, a lithograph that is ambiguously both an eyeball and a target, at Tatyanna Grosman’s Universal Limited Art Editions. His collaboration there launched his fascination and facility with printmaking, which would endure throughout his career. Johns became particularly intrigued with the fact that many prints are designed in reverse, a factor that has influenced not only his prints but also his paintings.

Attempting to categorize Johns, critics tended to think of him alongside other artists of the sixties who used recognizable imagery, specifically such Pop artists as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Jim Dine. Johns, however, disdained that appellation, as he indicated in an interview: “I don’t think of myself as a Pop artist. Generally people call the Pop movement single-minded. … It is technically restrictive and deals mostly with images. I am too much interested in dealing with images as working for form.” [3]

Extremely fertile and prolific, Johns invented a new visual vocabulary, which he was loath to explain. He preferred instead that the viewer approach the work and come to an independent conclusion. To this end, many of his artworks are labeled “untitled,” while others bear such obtuse monikers as Dutch Wives, According to What, or Corpse and Mirror. Generally aloof and uncommunicative about the meaning of his work, Johns changed course dramatically about 1983, producing images that were clearly self-reflective and autobiographical. He explained, “In my early work I tried to hide my personality, my psychological state, my emotions. … I sort of stuck to my guns for a while, but eventually it seemed like a losing battle. Finally, one must simply drop the reserve. I think some of the changes in my work relate to that.” [4]

In his late work, Johns’s debt to and fascination with earlier artists became more and more apparent, as he explored renditions of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Picasso’s Weeping Woman, and Mathias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. As he reached his sixtieth birthday in 1990, it also became clear that Johns was aware of the passage of time and his own mortality, most evident in a series of encaustics and related prints, The Seasons, in which he revisited emblems and motifs from each phase of his career.

While always highly regarded by other artists, Johns received recognition from another quarter in February 2011, when President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He was the first painter or sculptor to be given such an honor since Alexander Calder in 1977.

Notes:

[1] Johns sketchbook, in Riva Castleman, Jasper Johns: A Print Retrospective (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1986), 22–23, and Johns, quoted in Christian Gellhaar, Jasper Johns: Working Proofs (Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel, 1979), 39.

[2] Johns, quoted in Mark Stevens with Cathleen McGuigan, “Super Artist: Jasper Johns, Today’s Master,” Newsweek 90 (October 24, 1977), 73, in Kirk Varnedoe, Jasper Johns: A Retrospective (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 123.

[3] Johns, quoted in Jay Nash, and James Holstrand, “Zeroing in on Jasper Johns,” Literary Times (September 1965), reprinted in Kirk Varnedoe, ed., Jasper Johns: Writings, Sketchbook Notes, Interviews (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 104–105.

[4] Johns, quoted in April Bernard, and Mimi Thompson, "Johns on …" Vanity Fair 47, no. 2 (February 1984), 65, reprinted in Varnedoe, ed., Jasper Johns: Writings, 216–17.

Jasper Johns

born 1930

Always considered by himself and others to be a South Carolinian, Johns was born in Augusta, Georgia, in 1930, because the nearest hospital was located there. He spent his early childhood in rural Allendale, South Carolina, in the home of his paternal grandfather after the divorce of his parents. He also lived for a time with an aunt, and then with his mother and her new family. He studied mechanical drawing in high school in Sumter, where he was the class valedictorian, and attended the University of South Carolina for three semesters. At the urging of his art teachers, he moved to New York City in December 1948 at the age of eighteen.

In New York, Johns continued his studies at the Parsons School of Design and worked as a messenger boy and shipping clerk. His pursuit of art was interrupted by military service during the Korean War, first at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, then in Sendai, Japan. Discharged in 1953, he returned to New York, took a job at a bookstore, and visited exhibitions featuring Edvard Munch, Jackson Pollock, and Jacob Lawrence. After a few months he met Robert Rauschenberg, who, according to Johns, was “the first person I knew who was a real artist.” They began a close relationship that lasted six years, working together on windows for stores on Fifth Avenue, and occupying lofts near one another. Rauschenberg introduced Johns to the avant-garde dealer Leo Castelli, who would remain Johns’s representative for decades. [2]

Johns’s work was included in several important exhibitions, but his real breakthrough came with Flag, 1954–1955, an encaustic with collaged newspaper elements that startled the art world because of its overtly representational theme at a time when Abstract Expressionism was the dominant mode. This seminal piece was purchased, along with three others, for the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. All were encaustics, an ancient technique in which melted wax is the binder—a process Johns is credited with reviving.

In 1960, Johns made his first print, a lithograph that is ambiguously both an eyeball and a target, at Tatyanna Grosman’s Universal Limited Art Editions. His collaboration there launched his fascination and facility with printmaking, which would endure throughout his career. Johns became particularly intrigued with the fact that many prints are designed in reverse, a factor that has influenced not only his prints but also his paintings.

Attempting to categorize Johns, critics tended to think of him alongside other artists of the sixties who used recognizable imagery, specifically such Pop artists as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Jim Dine. Johns, however, disdained that appellation, as he indicated in an interview: “I don’t think of myself as a Pop artist. Generally people call the Pop movement single-minded. … It is technically restrictive and deals mostly with images. I am too much interested in dealing with images as working for form.” [3]

Extremely fertile and prolific, Johns invented a new visual vocabulary, which he was loath to explain. He preferred instead that the viewer approach the work and come to an independent conclusion. To this end, many of his artworks are labeled “untitled,” while others bear such obtuse monikers as Dutch Wives, According to What, or Corpse and Mirror. Generally aloof and uncommunicative about the meaning of his work, Johns changed course dramatically about 1983, producing images that were clearly self-reflective and autobiographical. He explained, “In my early work I tried to hide my personality, my psychological state, my emotions. … I sort of stuck to my guns for a while, but eventually it seemed like a losing battle. Finally, one must simply drop the reserve. I think some of the changes in my work relate to that.” [4]

In his late work, Johns’s debt to and fascination with earlier artists became more and more apparent, as he explored renditions of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Picasso’s Weeping Woman, and Mathias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. As he reached his sixtieth birthday in 1990, it also became clear that Johns was aware of the passage of time and his own mortality, most evident in a series of encaustics and related prints, The Seasons, in which he revisited emblems and motifs from each phase of his career.

While always highly regarded by other artists, Johns received recognition from another quarter in February 2011, when President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He was the first painter or sculptor to be given such an honor since Alexander Calder in 1977.

Notes:

[1] Johns sketchbook, in Riva Castleman, Jasper Johns: A Print Retrospective (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1986), 22–23, and Johns, quoted in Christian Gellhaar, Jasper Johns: Working Proofs (Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel, 1979), 39.

[2] Johns, quoted in Mark Stevens with Cathleen McGuigan, “Super Artist: Jasper Johns, Today’s Master,” Newsweek 90 (October 24, 1977), 73, in Kirk Varnedoe, Jasper Johns: A Retrospective (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 123.

[3] Johns, quoted in Jay Nash, and James Holstrand, “Zeroing in on Jasper Johns,” Literary Times (September 1965), reprinted in Kirk Varnedoe, ed., Jasper Johns: Writings, Sketchbook Notes, Interviews (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 104–105.

[4] Johns, quoted in April Bernard, and Mimi Thompson, "Johns on …" Vanity Fair 47, no. 2 (February 1984), 65, reprinted in Varnedoe, ed., Jasper Johns: Writings, 216–17.

Person TypeIndividual