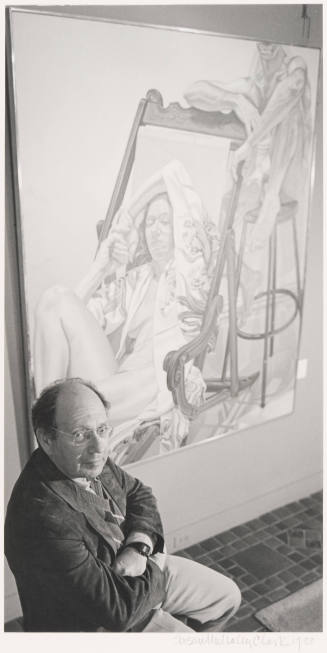

Philip Pearlstein

The art revolution known as Abstract Expressionism set in motion a variety of responses that included Pop, Minimalism, and Photorealism, as well as individual reactions by such twentieth-century giants as Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Philip Pearlstein. For many, the introduction of subject matter was key; for Pearlstein, the nude was paramount. Male and female nudes were viable subjects for artists in ancient Greece, in the Renaissance and Baroque periods, and especially in the nineteenth century when they became essential teaching tools in art academies. Yet, despite thousands of precursors, Pearlstein’s nudes are distinctive and resemble no others.

Pearlstein was born in 1924 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he displayed a precocious interest in art. He participated in several competitive art shows in high school, and two of his pieces were even reproduced in Life magazine while he was still a teenager. He attended the Carnegie Institute of Technology and earned his bachelor of fine arts degree in 1949, after a two-year plus stint in the army spent in Italy. With his classmate Andy Warhol, he then moved to New York City, where they were roommates for several months. Between 1949 and 1957, Pearlstein did layout and commercial design work to support himself. In 1955, he earned a masters degree in art history from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University; the subject of his thesis was the French Dadaist Francis Picabia. He spent 1958–1959 in Italy on a Fulbright grant.

A turning point came to Pearlstein in 1958 when he joined a group of artists who met weekly to draw from studio models. Alex Katz, Mary Frank, Philip Guston, and Jack Tworkov were fellow members. He shifted abruptly from painting expressive landscapes with emphatic brushwork to the depiction of nudes with smooth surfaces. This redirection coincided with a four-year teaching position at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. In an Art News article he admitted, “It seems madness on the part of any painter educated in the twentieth-century modes of picture-making to take as his subject the naked human figure, conceived as a self-contained entity possessed of its own dignity, existing in an inhabitable space, and viewed from a single vantage point.” [1]

Pearlstein’s role as a teacher—at Pratt Institute, as a visiting artist at Yale University, and for thirty years at Brooklyn College—reinforced his interest in nudes. In addition, he no longer had to produce commercial work, a fact which impacted his own work in an ironic way: “The thing that happened after I left that kind of precisionist work and got into teaching for a living was that my work became more precise. Once I wasn’t doing it for a living, the same impulse went into the painting. The paintings almost immediately got rid of expressionism and began working toward greater and greater clarity and precision.” [2] In addition, his layout work influenced his conception of cropping; he often depersonalized figures by cutting off their heads above the mouth.

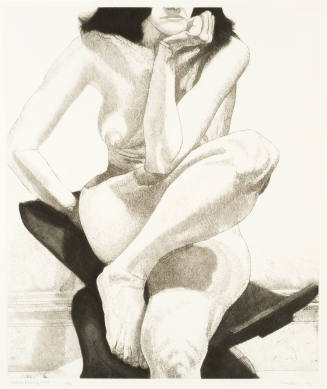

At first, Pearlstein first painted from his drawings, but then realized the importance of painting directly from live models. He has never used photographs as an aid. Typically, the models in his studio are lit by three overhead lamps, which emphasize every detail and create harsh shadows. Pearlstein does not idealize his subjects. Because of their nakedness and stark realism, his paintings, drawings, and prints have been controversial. In defense, he explains: “The nude figures I paint are unclothed artist’s models, as in the context of art schools, simply that in identity, not allegoric. They are posed in well-defined room spaces, not as beings lost in existential universal space. Specific, measurable, matter-of-fact, female and male, all parts are rendered with uniform focus; a documentation of a set-up in my studio.” [3]

In the early 1980s, Pearlstein began to include furniture and textiles in his compositions, to enliven the colors and to offer variety. He often let his models choose their props as well as their poses, but inevitably the expressions on their faces are of boredom. For them, it is a job. But the artist himself has not been bored; he has found an endless number of arrangements using the simplest tools. He maintains, “Only the mature artist who works from a model is capable of seeing the body for itself, only he has the opportunity for prolonged viewing. … What he actually sees is a fascinating kaleidoscope of forms; these forms, arranged in a particular position in space, constantly assume other dimensions, other contours and reveal other surfaces with the breathing and twitching.” [4]

Notes:

[1] Pearlstein, “Figure Paintings Today Are Not Made in Heaven,” Art News 61, no. 4 (Summer 1962), 39, quoted in Linda Nochlin, “Philip Pearlstein: Realism is Alive and Well in Georgia, Kansas, and Poughkeepsie,” in Philip Pearlstein (Athens, GA: Georgia Museum of Art, 1970), unpaginated.

[2] Pearlstein, quoted in Pat Mainardi, “Philip Pearlstein: Old Master of the New Realism,” Art News 75, no. 9 (November 1976), 74, quoted in Jerome Viola, The Painting and Technique of Philip Pearlstein (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1982), 33.

[3] Pearlstein quoted in Russell Bowman, Philip Pearlstein, and Irving Sandler, Philip Pearlstein: A Retrospective (New York: Alpine Fine Arts Collection, Limited, in association with the Milwaukee Art Museum, 1983), 15.

[4] Pearlstein, “Figure Paintings Today,” 52, quoted in Viola, The Painting and Teaching of Philip Pearlstein, 31.