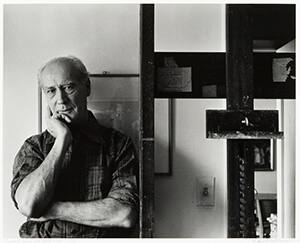

Skip to main contentBiographyCubism transformed twentieth-century art, first in Europe, then in America. It was a new way of looking at and analyzing space and form. Generally conservative, American artists and critics were slow to embrace Cubism and its numerous variations; nevertheless, George L.K. Morris (1905–1975) digested its tenets and evolved to become a major practitioner and outspoken champion of the style and abstraction in general.

Morris was born into affluent circumstances to a family with a distinguished lineage: in the eighteenth century, his ancestor, Lewis Morris, was chief justice of New York and governor of New Jersey, and Lewis’s son was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and delegate to the Continental Congress. Morris, the artist, graduated from the Groton School, in Groton, Massachusetts, in 1924, and finished Yale University as a member of the class of 1928. On a 1927 trip to Paris, his cousin, the artist and patron Albert E. Gallatin, introduced Morris to Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Constantin Brancusi. Morris later commented, “I had thought of Braque and Picasso as terrible artists, but when I met them I found them alive and totally different from the others.” [1] Morris went back to Paris two years later to study at the Académie Moderne with Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant, both of whom were working in individualistic variants of Cubism.

Returning to America, Morris built a studio on family property in the Berkshires which was modeled after designs by Le Corbusier for Ozenfant’s studio. Morris began to write poetry for the Yale Literary Review and quickly became involved in the promotion of abstract art. In 1936 he was one of the founders of American Abstract Artists, a membership organization whose mission was to foster abstract art through exhibitions, publications, and lectures. The following year he became the first art critic for the Partisan Review, and he regularly wrote exhibition brochures for his fellow abstractionists, such as Gallatin and Ilya Bolotowsky, as well as for his former teacher Léger. In a brochure for a group exhibition, Morris proclaimed: “Abstract paintings are a logical beginning. They are not puzzles; they are not difficult to understand; they need only be looked at, as one might look at a tree or a stone itself, and not as a representation of one.” [2]

In 1935, Morris married Suzy Frelinghuysen, also a member of an eminent family and also artistically inclined. In addition to being an abstract painter, she sang prestigious roles with the New York City Opera and in Europe. The couple split their time between New York, Paris, and Lenox, Massachusetts, where they built a modernist Bauhaus-inspired home designed by John Butler Swann. The adjoining studio and house, with a mural by Morris, are today open to visitors. Because of their comfortable circumstances, they were often referred to as the “Park Avenue Cubists,” even though they lived on Sutton Place.

Morris, who made sculpture as well as paintings, was included in the exhibition Five Contemporary American Concretionists mounted by Gallatin at his Museum of Living Art at New York University. The exhibition ran concurrently with and in apposition to one at the Museum of Modern Art, Cubism and Abstract Art, that included work by a single American, Alexander Calder. The term concretionist never took hold; instead Morris was sometimes described as the “American Juan Gris,” the Spanish cubist with a penchant for large, heavy forms.

In the foreword to his 1971 retrospective at the Hirschl & Adler Gallery, Morris addressed one of the primary concerns of Cubism: “Weight of tone and color, rhythmic indications across the canvas surface, a consideration of tactile values—a sensitive response to such elements as these will assist in the preservation of essential unity. Every spot can appear as sustained in two places at once. There is the position on the picture surface, and at the same time its role in the perspective scheme. Inevitably such a dual placement arouses pulsation; here new possibilities are offered, and these in turn require subjection.” [3] Toward the end of his career, in the 1950s, Morris was preoccupied with representing vortices and checkerboard patterns that anticipated Op Art.

In addition to his advocacy for abstract art, Morris was an outspoken critic of how art was taught. In 1936 he made a rather scathing assessment, which appeared in the alumni news of his alma mater, Yale: “There is little of a vital American art, until the art schools of the country are padlocked. They teach homebound students to mimic superficially museum art, which the public has been taught to feel art should be. They spend their time making copies of canvases Florentine janitors should have thrown out centuries ago. Art cannot be taught at all; it can only arise as the result of an impulse.” [4] Two decades later, with the ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism, American art would be deemed “vital” and “impulsive,” and would eventually undermine conventional art instruction.

Notes:

[1] Morris quoted in “Hermit in the Public Eye,” undated and unidentified clipping, Morris papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, reel D337.

[2] Morris quoted in brochure for American Abstract Artists National Exhibition, 1940, Morris papers.

[3] Morris quoted in Ward Jackson, “George L.K. Morris: Forty Years of Abstract Art,” Art Journal (Fall 1972), 155.

[4] Morris quoted in “G.L. Morris Holds Modern Art Exhibition,” Yale News, 1936, Morris papers.

Image Not Available

for George L. K. Morris

George L. K. Morris

1905 - 1975

Morris was born into affluent circumstances to a family with a distinguished lineage: in the eighteenth century, his ancestor, Lewis Morris, was chief justice of New York and governor of New Jersey, and Lewis’s son was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and delegate to the Continental Congress. Morris, the artist, graduated from the Groton School, in Groton, Massachusetts, in 1924, and finished Yale University as a member of the class of 1928. On a 1927 trip to Paris, his cousin, the artist and patron Albert E. Gallatin, introduced Morris to Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Constantin Brancusi. Morris later commented, “I had thought of Braque and Picasso as terrible artists, but when I met them I found them alive and totally different from the others.” [1] Morris went back to Paris two years later to study at the Académie Moderne with Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant, both of whom were working in individualistic variants of Cubism.

Returning to America, Morris built a studio on family property in the Berkshires which was modeled after designs by Le Corbusier for Ozenfant’s studio. Morris began to write poetry for the Yale Literary Review and quickly became involved in the promotion of abstract art. In 1936 he was one of the founders of American Abstract Artists, a membership organization whose mission was to foster abstract art through exhibitions, publications, and lectures. The following year he became the first art critic for the Partisan Review, and he regularly wrote exhibition brochures for his fellow abstractionists, such as Gallatin and Ilya Bolotowsky, as well as for his former teacher Léger. In a brochure for a group exhibition, Morris proclaimed: “Abstract paintings are a logical beginning. They are not puzzles; they are not difficult to understand; they need only be looked at, as one might look at a tree or a stone itself, and not as a representation of one.” [2]

In 1935, Morris married Suzy Frelinghuysen, also a member of an eminent family and also artistically inclined. In addition to being an abstract painter, she sang prestigious roles with the New York City Opera and in Europe. The couple split their time between New York, Paris, and Lenox, Massachusetts, where they built a modernist Bauhaus-inspired home designed by John Butler Swann. The adjoining studio and house, with a mural by Morris, are today open to visitors. Because of their comfortable circumstances, they were often referred to as the “Park Avenue Cubists,” even though they lived on Sutton Place.

Morris, who made sculpture as well as paintings, was included in the exhibition Five Contemporary American Concretionists mounted by Gallatin at his Museum of Living Art at New York University. The exhibition ran concurrently with and in apposition to one at the Museum of Modern Art, Cubism and Abstract Art, that included work by a single American, Alexander Calder. The term concretionist never took hold; instead Morris was sometimes described as the “American Juan Gris,” the Spanish cubist with a penchant for large, heavy forms.

In the foreword to his 1971 retrospective at the Hirschl & Adler Gallery, Morris addressed one of the primary concerns of Cubism: “Weight of tone and color, rhythmic indications across the canvas surface, a consideration of tactile values—a sensitive response to such elements as these will assist in the preservation of essential unity. Every spot can appear as sustained in two places at once. There is the position on the picture surface, and at the same time its role in the perspective scheme. Inevitably such a dual placement arouses pulsation; here new possibilities are offered, and these in turn require subjection.” [3] Toward the end of his career, in the 1950s, Morris was preoccupied with representing vortices and checkerboard patterns that anticipated Op Art.

In addition to his advocacy for abstract art, Morris was an outspoken critic of how art was taught. In 1936 he made a rather scathing assessment, which appeared in the alumni news of his alma mater, Yale: “There is little of a vital American art, until the art schools of the country are padlocked. They teach homebound students to mimic superficially museum art, which the public has been taught to feel art should be. They spend their time making copies of canvases Florentine janitors should have thrown out centuries ago. Art cannot be taught at all; it can only arise as the result of an impulse.” [4] Two decades later, with the ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism, American art would be deemed “vital” and “impulsive,” and would eventually undermine conventional art instruction.

Notes:

[1] Morris quoted in “Hermit in the Public Eye,” undated and unidentified clipping, Morris papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, reel D337.

[2] Morris quoted in brochure for American Abstract Artists National Exhibition, 1940, Morris papers.

[3] Morris quoted in Ward Jackson, “George L.K. Morris: Forty Years of Abstract Art,” Art Journal (Fall 1972), 155.

[4] Morris quoted in “G.L. Morris Holds Modern Art Exhibition,” Yale News, 1936, Morris papers.

Person TypeIndividual