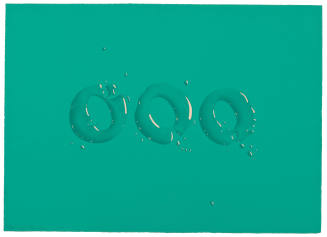

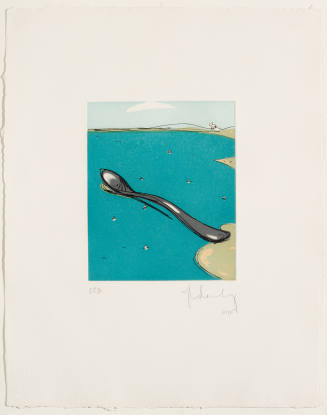

Skip to main contentBiographyEver since the Renaissance, pictorial illusionism has preoccupied painters who wanted to convey three-dimensional space on two-dimensional surfaces. With the advent of modernism in the early twentieth century and its emphasis on abstraction, artists questioned the role of the picture plane. A stylistically diverse artist who worked with unorthodox materials, Richard Artschwager challenged the devices used to create an illusion of space on flat surfaces. He received considerable critical recognition for his singular achievement in bridging modernism with Pop and such post-Abstract Expressionist movements as Minimal, Photo-Realist and Conceptual Art. In addition, he inspired a later generation of artists who emerged in the 1980s, perhaps most notably Peter Halley and Jeff Koons.

Artschwager was born in Washington, D.C., but the family moved to Las Cruces, New Mexico, after his father, a geneticist who studied plant pathology, was diagnosed with tuberculosis. His mother had studied art at the Munich Academy as well as at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. As a young man, Artschwager studied chemistry and mathematics at his father’s alma mater, Cornell University, until World War II interrupted his sophomore year. He served in field artillery and tactical intelligence in France and England and then as a counterintelligence officer in postwar Vienna, where he met his future wife. Upon his discharge, he returned to Cornell and finished his undergraduate degree in physics, although during his final semester he enrolled in drawing and painting classes. Realizing he did not want to be a scientist, preferring instead a more creative career, he moved to New York and held numerous jobs, such as commercial baby photographer.

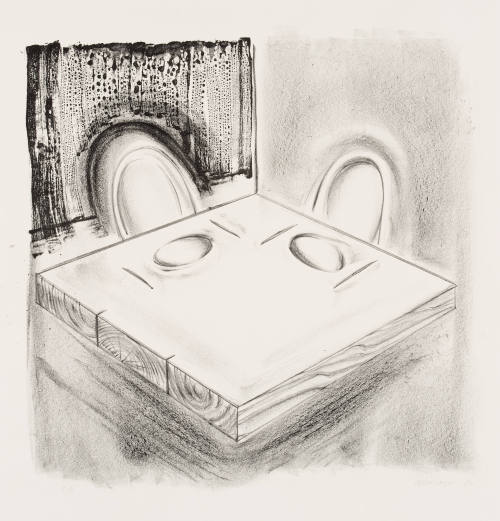

From 1949–1950, using the G.I. Bill, Artschwager attended the New York art school of Amedée Ozenfant, a proponent of Purism, a post-Cubism art movement. In the early 1950s, Artschwager became a cabinetmaker and within a few years was designing and manufacturing furniture for Pottery Barn and The Workbench, among other clients. He lost much of this work in a studio fire in 1958, which proved to be the break that freed him to become an artist. During the next decade, he made work based on photographs primarily drawn from newspapers. His 1963–1964 wood sculpture Table and Chair marked his first use of Formica, an industrial material that inspired him because “it’s a picture of something at the same time it’s an object.” [1] Artschwager had created a highly complex idea through relatively simple means: an artwork that reads as two-dimensional when it is three-dimensional, and one that the viewer understands as an abstract table and chair delineated by the three different surface treatments of the melamine laminate: white, wood grain, and light brown.

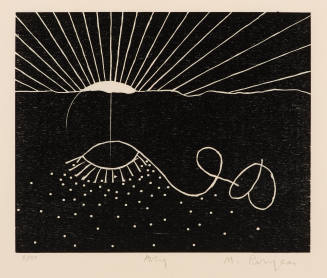

Artschwager had his first exhibition with the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1964. Despite growing attention for his work, however, it did not fit with the prevalent styles of the time. Richard Armstrong, curator and art historian, said of the sculptures: “They were physically unappealing when physicality was paramount. And while the Minimalists claimed their work was devoid of literary meaning, Artschwager’s were full of meanings.” [2] In 1975, seeking inspiration at a time when he was unsure of his direction, Artschwager made an inventory of items in one of his drawings, an interior scene. He produced a series of fifty-three ink drawings called Basket Table Door Window Mirror Rug. Of these works, art historian Bonnie Clearwater said, “Language became the model for these works and the permutations of the objects in his paintings and drawings are endless.” [3] In 1988, Artschwager had a major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art and his work has also been included in numerous major exhibitions in this country and internationally.

Notes:

[1] Jan McDevitt, “The Object: Still Life,” Craft HorizonsXXV, no. 5 (September–October 1965), 28–30, 54, quoted in Lisa Corrin, et al, Richard Artschwager: Up and Across (Nürnberg, Germany: Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg 2001), 130–132.

[2] Steven Henry Madoff, “Richard Artschwager’s Sleight of Mind,” Art News 87 (January 1988), 117.

[3] Bonnie Clearwater, Richard Artschwager: Painting Then and Now (North Miami, FL: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2003), 30.

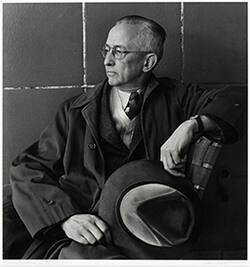

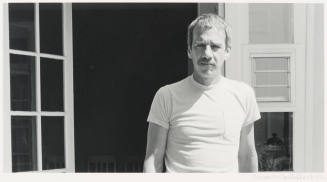

Richard Artschwager

1923 - 2013

Artschwager was born in Washington, D.C., but the family moved to Las Cruces, New Mexico, after his father, a geneticist who studied plant pathology, was diagnosed with tuberculosis. His mother had studied art at the Munich Academy as well as at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. As a young man, Artschwager studied chemistry and mathematics at his father’s alma mater, Cornell University, until World War II interrupted his sophomore year. He served in field artillery and tactical intelligence in France and England and then as a counterintelligence officer in postwar Vienna, where he met his future wife. Upon his discharge, he returned to Cornell and finished his undergraduate degree in physics, although during his final semester he enrolled in drawing and painting classes. Realizing he did not want to be a scientist, preferring instead a more creative career, he moved to New York and held numerous jobs, such as commercial baby photographer.

From 1949–1950, using the G.I. Bill, Artschwager attended the New York art school of Amedée Ozenfant, a proponent of Purism, a post-Cubism art movement. In the early 1950s, Artschwager became a cabinetmaker and within a few years was designing and manufacturing furniture for Pottery Barn and The Workbench, among other clients. He lost much of this work in a studio fire in 1958, which proved to be the break that freed him to become an artist. During the next decade, he made work based on photographs primarily drawn from newspapers. His 1963–1964 wood sculpture Table and Chair marked his first use of Formica, an industrial material that inspired him because “it’s a picture of something at the same time it’s an object.” [1] Artschwager had created a highly complex idea through relatively simple means: an artwork that reads as two-dimensional when it is three-dimensional, and one that the viewer understands as an abstract table and chair delineated by the three different surface treatments of the melamine laminate: white, wood grain, and light brown.

Artschwager had his first exhibition with the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1964. Despite growing attention for his work, however, it did not fit with the prevalent styles of the time. Richard Armstrong, curator and art historian, said of the sculptures: “They were physically unappealing when physicality was paramount. And while the Minimalists claimed their work was devoid of literary meaning, Artschwager’s were full of meanings.” [2] In 1975, seeking inspiration at a time when he was unsure of his direction, Artschwager made an inventory of items in one of his drawings, an interior scene. He produced a series of fifty-three ink drawings called Basket Table Door Window Mirror Rug. Of these works, art historian Bonnie Clearwater said, “Language became the model for these works and the permutations of the objects in his paintings and drawings are endless.” [3] In 1988, Artschwager had a major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art and his work has also been included in numerous major exhibitions in this country and internationally.

Notes:

[1] Jan McDevitt, “The Object: Still Life,” Craft HorizonsXXV, no. 5 (September–October 1965), 28–30, 54, quoted in Lisa Corrin, et al, Richard Artschwager: Up and Across (Nürnberg, Germany: Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg 2001), 130–132.

[2] Steven Henry Madoff, “Richard Artschwager’s Sleight of Mind,” Art News 87 (January 1988), 117.

[3] Bonnie Clearwater, Richard Artschwager: Painting Then and Now (North Miami, FL: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2003), 30.

Person TypeIndividual