Arnold Newman

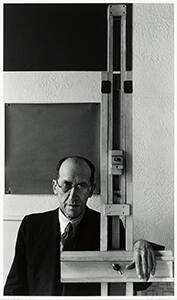

When photography was first invented in the mid-nineteenth century, its primary purpose was to provide inexpensive likenesses; gradually it evolved to record historic events and picturesque landscapes. Portraiture by both professionals and amateurs remains one of the camera’s main functions. Arnold Newman (1918–2006) revolutionized portrait photography through his innovative “environmental” approach in which he placed the sitter in a meaningful context, rather than against a neutral studio backdrop.

Newman was born in New York City, but soon afterward his family moved to Atlantic City, New Jersey, where they worked in dry goods and then the hotel business. In 1934, his parents opened a hotel in Miami Beach and it was there that Newman began to display an interest in art. After graduation from high school, he was awarded a working scholarship at the University of Miami in Coral Gables where he studied art. But his college career was short-lived due to financial problems, so he accepted a position with a studio photographer in Philadelphia and made forty-nine-cent portraits. At the end of 1939, he returned to West Palm Beach to run a photography studio. After meeting and receiving encouragement from noted photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz and from Beaumont Newhall, director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, Newman spent 1941–1942 in New York. He returned to Miami Beach for induction into the military, but his service was deferred. He remained there until 1946, when he settled in New York.

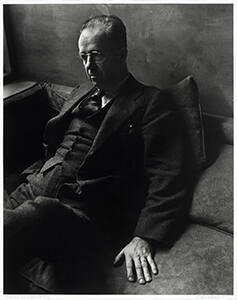

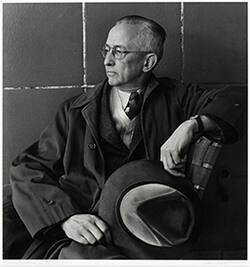

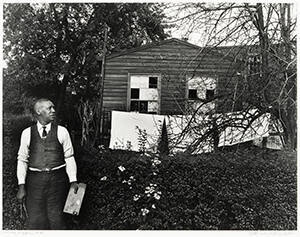

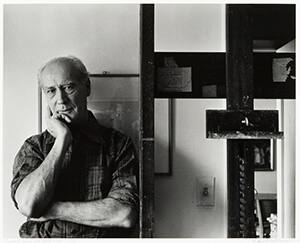

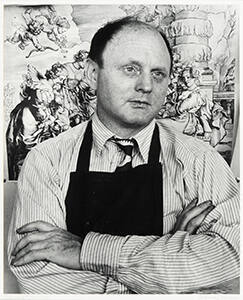

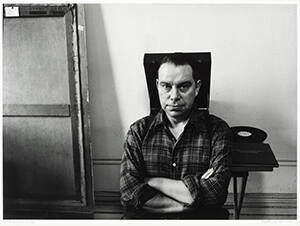

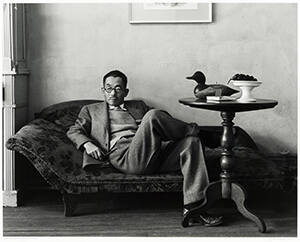

One of Newman’s greatest accomplishments was his series of photographs of artists, begun in 1941, which served as the basis for his future work. He explained “it just happened. … I was not so much interested in documentation as in conveying my impressions of individuals by means of the ever-expanding language of my medium. … I wanted to work with positive personalities, people who did something with their lives, and with life. Artists were not the only ones who interested me, but at that time they were the most accessible, and most important, they accepted and encouraged me.” A one-man exhibition, Artists Look Like This, was mounted at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1945–1946. Wanting to include Georgia O’Keeffe, he called her, explaining his project, and her response was somewhat cool. Newman recalled “to prove I wasn’t a novice, I said, ‘Miss O’Keeffe, I have already photographed forty-six artists.’ ‘Oh,’ she replied caustically, ‘are there that many artists in America?’” [1] Forty-two years later, Newman shot O’Keeffe again; the end result is a compelling image of her in profile against a blank white canvas above which hover a cow skull with horns. Reynolda House’s eight photographs are of artists represented in the permanent collection, with the exception of Piet Mondrian and Yasuo Kuniyoshi.

Gradually success came to Newman, and he began portrait assignments for Harper’s Bazaar, Fortune, and Life. He traveled extensively; he spent most of 1954 in Europe, and four years later clocked 24,000 miles in Africa for Holiday. His list of sitters is extensive and impressive, including the most notable figures of his day: John F. Kennedy, Richard M. Nixon, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Ayn Rand, Robert Moses, Henry Ford II, Konrad Adenauer, Frank Lloyd Wright, Yasser Arafat, and Bill Clinton. Even with these powerful individuals, Newman managed to stay in control, though he would accept suggestions from his sitters. “Inevitably, photographs—like all art forms—reflect the time in which they are made. In general, I ‘build’ rather than ‘take’ a photograph, to differentiate it from the ‘candid’ picture. … The subject’s environment—its furniture, vistas, and objects—provides not only the building blocks of design and composition but also the atmosphere created by the subject. These objects that surround the subject are not props, and should not be, but are real integral parts of his life.” [2]

From a technical point of view, Newman preferred whenever possible to work with natural light. If he had to use lights, he tended to bounce and reflect them, rather than direct them toward his sitter. His cameras—a 4x5 view camera on a tripod and a Single Lens Reflex 35mm camera—were selected for their flexibility. His preference was to hold his camera while shooting, thinking that was less intimidating to his subject. He worked largely in black and white, and chose to keep the developing and printing as simple as possible so he could concentrate on the creative aspect of shooting.

During the height of his career, Newman was not the only portrait photographer in New York working for the major magazines of the day. He explained how his work was different from the likes of Richard Avedon and Irving Penn: “They totally control the situation in the studio, and I am always taking a chance wherever I go. … Some times it defeats me. But I would rather take that chance where a certain element will give me something to work with.” [3]

Notes:

[1] Arnold Newman and Henry Geldzhaler, Artists Portraits from four Decades by Arnold Newman (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1980), 17.

[2] Newman quoted in Alan Fern and Arnold Newman, Arnold Newman’s Americans (Boston: Bulfinch/Little Brown & Co., in association with the National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution, 1992), 23.

[3] Newman quoted in Fern and Newman, Arnold Newman’s Americans, 10.