Skip to main contentBiographyA highly original artist whose colossal outdoor sculptures are icons of Pop art, Claes Oldenburg is also a prolific printmaker, draftsman, painter, and performance artist. He was born in Sweden in 1929 but moved with his family to New York as an infant. His father’s career as a diplomat took them to Oslo when Oldenburg was a child, but, by the time he was seven, they had settled permanently in Chicago. An imaginative child, Oldenburg invented a fictitious city called Neubern and fashioned all sorts of objects, such as newspapers and airplanes, for it. [1] These creative acts foreshadowed his artistic production as an adult.

Oldenburg studied literature, theater, and art at Yale University. After graduating, he returned to Chicago and worked briefly as a newspaper reporter before devoting himself to art full-time. He took classes at the Art Institute of Chicago and, during his free time, drew almost incessantly. In 1956, he moved to New York City, the center of the art world, where Abstract Expressionism was the dominant mode of painting. While Oldenburg admired Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, abstract art did not appeal to him. Instead, his paintings and drawings of the 1950s feature still lifes and figure studies. His work at this time also reveals a repetition of certain motifs—milkweed pods, for example—that would characterize his entire career.

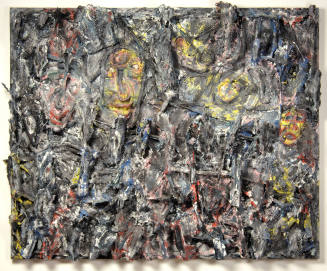

In New York, Oldenburg met a group of young artists, including Allan Kaprow, Red Grooms, and Jim Dine, who were challenging the strictures of Abstract Expressionism. They felt that painting was too confining, and they sought ways to move art off the two-dimensional canvas and to engage the senses beyond sight alone. The “gesture” that had been so central to the creation of art in Abstract Expressionism now became the art itself in performance pieces called Happenings. Oldenburg was drawn to this group, finding an intellectual and spiritual home in their bohemian community. He was particularly inspired by Grooms’s performance piece The Burning Building, 1959, which he saw several times. [2]

To make a living during this period, Oldenburg worked in the library of the Cooper Union Museum and School of Art, studying the books he shelved and absorbing as much as he could about the history of art. His first significant exhibition took place in the basement of the Judson Memorial Church in Washington Square, which had been turned into a gallery of sorts by the young artists in his circle. The exhibition featured Oldenburg’s drawings and poems, as well as some crudely fashioned objects that the artist formed out of wood and paper and painted white. [3] Building on his desire to move off the canvas, Oldenburg conceived of the exhibition not simply as a collection of works to be viewed individually but as an entire environment in which the viewer experiences the pieces as a whole.

This shift in approach led to the creation of another environment, The Street, 1960, in which Oldenburg examined the chaos and degradation of urban poverty—a condition with which he, as a struggling artist, was unfortunately familiar. He also staged performances in the installation. After The Street, Oldenburg created The Store, 1961, an actual store for which the artist formed faux food and clothing out of plaster-covered muslin. The “sale” of the objects was the performative aspect of the environment, enabling the artist to comment wryly on the commodification of post-war American culture.

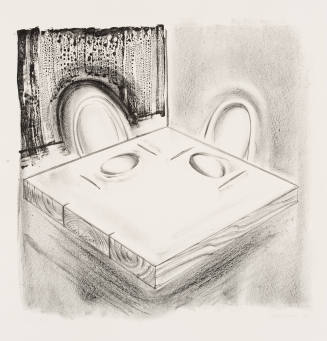

The creation of The Street and The Store stemmed in part from Oldenburg’s desire to make art accessible to as many people as possible—to move it out of the rarified atmosphere of the gallery and museum and put it, literally, on street level. This radical notion also contributed to the artist’s choice of subject matter—everyday objects that are instantly recognizable—which aligned him with other Pop artists. In the 1960s, Oldenburg began to experiment with the scale of those objects. Taking inspiration from the fabrication of the everyday objects that he created for The Store, Oldenburg began magnifying them, crafting huge slices of cake, hamburgers, tubes of toothpaste, and pool balls. He also experimented with forms, making hard objects soft by stitching together large pieces of vinyl and then stuffing them: soft toilets, hand mixers, fans, scissors, and toasters. By making useful objects useless, he invites viewers to pay attention to things in their lives that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Oldenburg created his first large outdoor sculpture in 1969, when he installed Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks on the Yale University campus, directly across from a monument paying tribute to Yale men lost during World War I. [4] Created in the midst of the Vietnam war, the piece made a pointed anti-war statement by irreverently combining the tools of war (the tank treads) with a banal object (the lipstick).

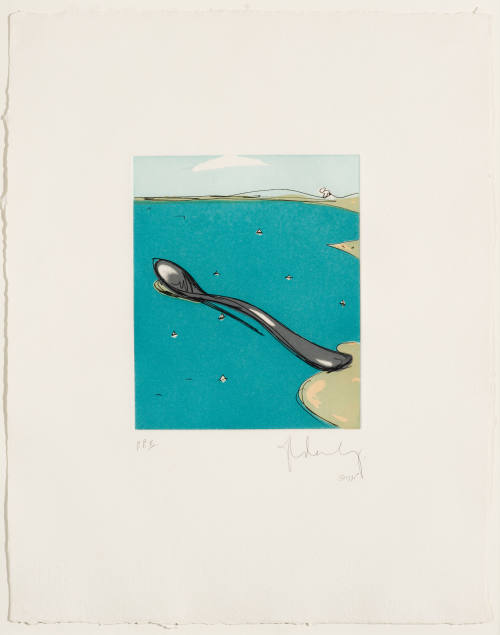

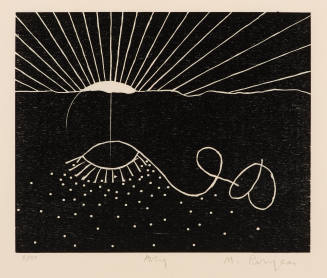

Throughout the years of creating the large outdoor sculptures for which he is best known, Oldenburg continued drawing. Often, the drawings relate to the sculptures, but they are not mere preparatory sketches. Instead, they provide Oldenburg with another medium to experiment with according to his current fixation: clothespins, ice cream bars, plugs, screws, pencils, apple cores, and spoons. Certain motifs appear and reappear in his work, combined and re-imagined in countless ways. Oldenburg analyzes the objects from every angle and sometimes at different stages of change or decay, obsessively creating and recreating the image. Both the obsessive repetition and the experiments in scale in the artist’s work cause the banal objects he treats to take on weight and significance they do not have in everyday life.

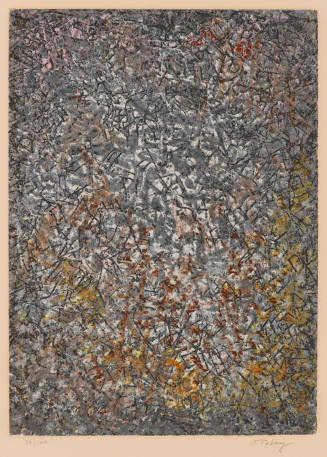

In 1968, Oldenburg began printmaking in earnest. Earlier efforts in the medium had been sporadic; often, the artist had used printmaking as a way of creating support materials—posters or fake business cards and letterhead—for other projects or performances. Oldenburg at first expressed frustration with the technical precision required for printmaking, asserting that the practice is “an excruciatingly unpleasant activity, like going to the hospital for an operation.” [5] But he found success when he began working with major print shops such as Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, Tanglewood Press in New York, and Landfall Press in Chicago. Since then, printmaking has become an important component of his work, offering him yet another method for contemplating his objects.

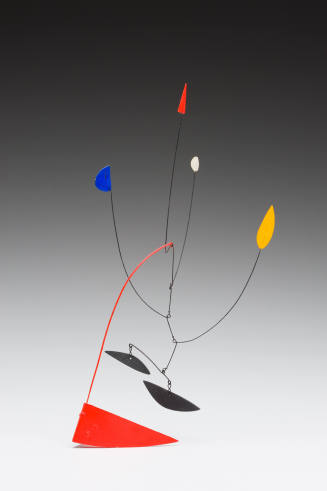

In the 1970s, Oldenburg began collaborating on the large outdoor sculptures with the art historian and writer Coosje van Bruggen; they married in 1977. Since then, sculptures have become more and more complex. Fabricated out of Cor-Ten steel and often painted in bright colors, the pieces relate to their environments in sensitive and witty ways. Huge bicycle parts appear to be buried in the landscape in Buried Bicycle, Parc de la Villette, Paris, 1990. Giant badminton birdies appear scattered haphazardly across a lawn in Shuttlecocks, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1994. Oversized pool balls rest on green grass that mimics a pool table in Pool Balls, Aaseeterrassen, Munster, Germany, 1977. A tall, slender clothespin in Philadelphia mirrors the height and form of the City Hall tower behind it in Clothespin, 1976. An enormous white spoon arcs elegantly over a park pond, with a giant red cherry balanced just on its edge in Spoonbridge and Cherry, Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, Walker Art Center, 1988. A massive blue trowel juts out of the earth, as if a giant has left behind his gardening tools in Trowel I, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, The Netherlands, 1976. Playful, iconic, and instantly recognizable, the large outdoor sculptures satisfied Oldenburg’s desire to make art that is accessible to everyone.

In addition to his prolific artistic output, Oldenburg is also a talented writer. In the early 1960s, he created an alternate persona called Ray Gun, through whom he issued artistic manifestos: “Seek out banality, seek out what opposes it or what is excluded from its domain and triumph over it—the city filth, the evils of advertising, the disease of success, popular culture. …Look for beauty where it is not supposed to be found.” [6]

Notes:

[1] Barbara Rose, Claes Oldenburg (New York: The Museum of Modern Art. Distributed by New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, CT, 1970), 19.

[2] Rose, Claes Oldenburg, 40.

[3] Rose, Claes Oldenburg, 27.

[4] Germano Celant, Claes Oldenburg: An Anthology (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1995), 129.

[5] Richard H. Axsom and David Platzker, Printed Stuff: Prints, Posters, and Ephemera by Claes Oldenburg. A Catalogue Raisonné 1958–1996 (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Madison Art Center, Wisconsin, 1997), 19 and 21.

[6] Rose, Claes Oldenburg, 46.

Claes Oldenburg

1929 - 2022

Oldenburg studied literature, theater, and art at Yale University. After graduating, he returned to Chicago and worked briefly as a newspaper reporter before devoting himself to art full-time. He took classes at the Art Institute of Chicago and, during his free time, drew almost incessantly. In 1956, he moved to New York City, the center of the art world, where Abstract Expressionism was the dominant mode of painting. While Oldenburg admired Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, abstract art did not appeal to him. Instead, his paintings and drawings of the 1950s feature still lifes and figure studies. His work at this time also reveals a repetition of certain motifs—milkweed pods, for example—that would characterize his entire career.

In New York, Oldenburg met a group of young artists, including Allan Kaprow, Red Grooms, and Jim Dine, who were challenging the strictures of Abstract Expressionism. They felt that painting was too confining, and they sought ways to move art off the two-dimensional canvas and to engage the senses beyond sight alone. The “gesture” that had been so central to the creation of art in Abstract Expressionism now became the art itself in performance pieces called Happenings. Oldenburg was drawn to this group, finding an intellectual and spiritual home in their bohemian community. He was particularly inspired by Grooms’s performance piece The Burning Building, 1959, which he saw several times. [2]

To make a living during this period, Oldenburg worked in the library of the Cooper Union Museum and School of Art, studying the books he shelved and absorbing as much as he could about the history of art. His first significant exhibition took place in the basement of the Judson Memorial Church in Washington Square, which had been turned into a gallery of sorts by the young artists in his circle. The exhibition featured Oldenburg’s drawings and poems, as well as some crudely fashioned objects that the artist formed out of wood and paper and painted white. [3] Building on his desire to move off the canvas, Oldenburg conceived of the exhibition not simply as a collection of works to be viewed individually but as an entire environment in which the viewer experiences the pieces as a whole.

This shift in approach led to the creation of another environment, The Street, 1960, in which Oldenburg examined the chaos and degradation of urban poverty—a condition with which he, as a struggling artist, was unfortunately familiar. He also staged performances in the installation. After The Street, Oldenburg created The Store, 1961, an actual store for which the artist formed faux food and clothing out of plaster-covered muslin. The “sale” of the objects was the performative aspect of the environment, enabling the artist to comment wryly on the commodification of post-war American culture.

The creation of The Street and The Store stemmed in part from Oldenburg’s desire to make art accessible to as many people as possible—to move it out of the rarified atmosphere of the gallery and museum and put it, literally, on street level. This radical notion also contributed to the artist’s choice of subject matter—everyday objects that are instantly recognizable—which aligned him with other Pop artists. In the 1960s, Oldenburg began to experiment with the scale of those objects. Taking inspiration from the fabrication of the everyday objects that he created for The Store, Oldenburg began magnifying them, crafting huge slices of cake, hamburgers, tubes of toothpaste, and pool balls. He also experimented with forms, making hard objects soft by stitching together large pieces of vinyl and then stuffing them: soft toilets, hand mixers, fans, scissors, and toasters. By making useful objects useless, he invites viewers to pay attention to things in their lives that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Oldenburg created his first large outdoor sculpture in 1969, when he installed Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks on the Yale University campus, directly across from a monument paying tribute to Yale men lost during World War I. [4] Created in the midst of the Vietnam war, the piece made a pointed anti-war statement by irreverently combining the tools of war (the tank treads) with a banal object (the lipstick).

Throughout the years of creating the large outdoor sculptures for which he is best known, Oldenburg continued drawing. Often, the drawings relate to the sculptures, but they are not mere preparatory sketches. Instead, they provide Oldenburg with another medium to experiment with according to his current fixation: clothespins, ice cream bars, plugs, screws, pencils, apple cores, and spoons. Certain motifs appear and reappear in his work, combined and re-imagined in countless ways. Oldenburg analyzes the objects from every angle and sometimes at different stages of change or decay, obsessively creating and recreating the image. Both the obsessive repetition and the experiments in scale in the artist’s work cause the banal objects he treats to take on weight and significance they do not have in everyday life.

In 1968, Oldenburg began printmaking in earnest. Earlier efforts in the medium had been sporadic; often, the artist had used printmaking as a way of creating support materials—posters or fake business cards and letterhead—for other projects or performances. Oldenburg at first expressed frustration with the technical precision required for printmaking, asserting that the practice is “an excruciatingly unpleasant activity, like going to the hospital for an operation.” [5] But he found success when he began working with major print shops such as Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, Tanglewood Press in New York, and Landfall Press in Chicago. Since then, printmaking has become an important component of his work, offering him yet another method for contemplating his objects.

In the 1970s, Oldenburg began collaborating on the large outdoor sculptures with the art historian and writer Coosje van Bruggen; they married in 1977. Since then, sculptures have become more and more complex. Fabricated out of Cor-Ten steel and often painted in bright colors, the pieces relate to their environments in sensitive and witty ways. Huge bicycle parts appear to be buried in the landscape in Buried Bicycle, Parc de la Villette, Paris, 1990. Giant badminton birdies appear scattered haphazardly across a lawn in Shuttlecocks, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1994. Oversized pool balls rest on green grass that mimics a pool table in Pool Balls, Aaseeterrassen, Munster, Germany, 1977. A tall, slender clothespin in Philadelphia mirrors the height and form of the City Hall tower behind it in Clothespin, 1976. An enormous white spoon arcs elegantly over a park pond, with a giant red cherry balanced just on its edge in Spoonbridge and Cherry, Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, Walker Art Center, 1988. A massive blue trowel juts out of the earth, as if a giant has left behind his gardening tools in Trowel I, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, The Netherlands, 1976. Playful, iconic, and instantly recognizable, the large outdoor sculptures satisfied Oldenburg’s desire to make art that is accessible to everyone.

In addition to his prolific artistic output, Oldenburg is also a talented writer. In the early 1960s, he created an alternate persona called Ray Gun, through whom he issued artistic manifestos: “Seek out banality, seek out what opposes it or what is excluded from its domain and triumph over it—the city filth, the evils of advertising, the disease of success, popular culture. …Look for beauty where it is not supposed to be found.” [6]

Notes:

[1] Barbara Rose, Claes Oldenburg (New York: The Museum of Modern Art. Distributed by New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, CT, 1970), 19.

[2] Rose, Claes Oldenburg, 40.

[3] Rose, Claes Oldenburg, 27.

[4] Germano Celant, Claes Oldenburg: An Anthology (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1995), 129.

[5] Richard H. Axsom and David Platzker, Printed Stuff: Prints, Posters, and Ephemera by Claes Oldenburg. A Catalogue Raisonné 1958–1996 (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Madison Art Center, Wisconsin, 1997), 19 and 21.

[6] Rose, Claes Oldenburg, 46.

Person TypeIndividual