Mark Tobey

Critics and art historians like to place artists in schools: the Hudson River School, the New York School, the Northwest School, even though there were no classrooms, the associations were sometimes tenuous, and the groups often lacked cohesion. Such is the case for the Northwest School, which was celebrated in a 1953 article “Mystic Painters of the Northwest” in Life magazine, several years after the purported participants dispersed. While it is true that during the late 1930s and early 1940s, Mark Tobey, Kenneth Callahan, Guy Anderson, and Morris Graves lived and worked in the Seattle area, showed art in the same exhibitions, and even shared a penchant for somber compositions, the foursome were never a “school” per se. The oldest, Tobey, and the youngest, Graves, were once close, but their relationship became acrimonious after the former accused the latter of copying: “He stole my stuff. Without my ideas he would be nothing. … He used to come here night after night … lie on the floor, ask me to show him my work, and pore over my paintings. Study them. Then stole them. Like a thief in the night.” [1]

Of the four artists, Tobey (1890–1976) was the only one not native to the Northwest; he was born in rural Centerville, Wisconsin. After studies at the Art Institute of Chicago, he moved to New York, where he worked as an illustrator for such women’s magazines as McCall’s and Vogue. He was also a successful portraitist, and a selection of his portraits was exhibited at the prestigious Knoedler gallery in 1917. The following year he embraced Bahá’í, a universalist faith that emphasizes the spiritual unity of mankind and believes that Abraham, the Buddha, Jesus, Mohammed, and the Báb are divine messengers of one God. Bahá’í is also pacifistic and anti-communist. In 1922, Tobey moved to Seattle, a dramatic contrast to cosmopolitan New York, a city he castigated in a local newspaper: “Cities should treasure their talent and not let their artists be swallowed up in impersonal art centers like New York.” [2] In his adopted home, Tobey found a relaxed atmosphere, diffused light, easy access to the outdoors, and regular support from the Seattle Art Museum, which opened in 1933.

For much of his early career, Tobey supported himself as a teacher, first at the innovative Cornish School of the Allied Arts and then at his own Free and Creative School. From 1931 to 1938 he taught at Dartington Hall, a progressive coeducational boarding school in Devonshire, England. He was a respected instructor who encouraged his students to follow their intuition, as indicated by some advice he once gave a student: “Don’t start a picture in a cold frame of being. Form is generated from heat. … Seek the rhythms underlying your subject matter. Foster them within yourself and re-enact the rhythm with yourself.” [3]

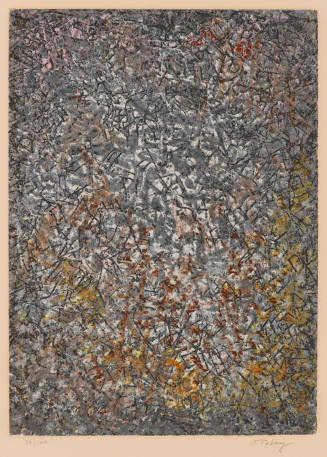

Tobey began to study Oriental calligraphy shortly after his arrival in Seattle, which fueled his interest in the art and philosophy of the Far East. In 1934, he traveled to Japan and spent a month at a Zen monastery near Kyoto. He developed his signature style, called “white writing,” which consists of thin calligraphic lines overlaid on darker hues—a concept derived from notan, the Japanese study of tonal values. His close friend and correspondent, the German-American artist Lyonel Feininger, explained this persistent motif: “The moving white lines symbolize the light, the unifying thought which flows across the compartments of life, and these give strength to the spirit, and are constantly renewing their energies so that there can be a greater understanding of life.” [4] This unifying aspect of the white writing parallels Tobey’s Bahá’í beliefs.

Music was another area of interest for Tobey, who began to take piano and theory lessons at the age of fifty-one, and even composed music for flute and piano. Another passion was collecting Native American artifacts, especially Tlingit and Haida Indian objects, along with Oriental pieces. These often served as sources of inspiration for his work. Using his background in figure studies, Tobey spent hours sketching people at the Pike Place Market and later came to its defense when it was threatened with demolition in the early 1960s.

Beginning in the late 1940s, Tobey’s career flourished. In 1951, the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted a retrospective, which traveled to San Francisco, Seattle, and Santa Barbara. In group shows, he was often linked with the Abstract Expressionists, such as Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and Adolph Gottlieb, all of whom, at times, incorporated calligraphy in their work. In correspondence with his dealer, he opined, “Standing as I am here between East and West cultures I sometimes get dizzy as I find I can’t always make a synthesis and also that I admire both paths which should and will, I suppose, merge.” In 1960, disenchanted with life and art in America, Tobey moved to Basel, Switzerland, where he died at age eighty-five. This relocation may also have been prompted by his lifelong love of the Swiss artist Paul Klee, whose similarity he acknowledged: “Anyway, I don’t resemble anyone but have some kin to Klee. I get pretty depressed with modern art. Nothing can grow that is watched too much, nor does the kettle boil either.” [5]

Notes:

[1] See Sheryl Conkleton and Laura Landau, Northwest Mythologies: The Interactions of Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan, and Guy Anderson (Tacoma, WA: Tacoma Art Museum in association with the University of Washington Press, 2003), and Tobey statement recalled by Elizabeth Bayley Willis quoted in Deloris Tarzan Ament, Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2002), 27, quoted in Conkleton and Landau, Northwest Mythologies, 24.

[2] Tobey quoted in a 1934 Seattle newspaper in Betty Bowen, Tobey’s 80, A Retrospective (Seattle, WA: Seattle Art Museum and University of Seattle Press, 1970), unpaginated.

[3] Tobey to Helen Boyd, from Dartington Hall, Helen Boyd Keen Archives, quoted in Conkleton and Landau, Northwest Mythologies, 43.

[4] Feininger quoted in Feininger and Tobey. Years of Friendship 1944–1956. The Complete Correspondence (New York: Achim Moeller Fine Art, 1991).

[5] Tobey correspondence, August 1957 and May 1958, quoted in “Excerpts from the Correspondence of Tobey to Marian Willard,” Mark Tobey. Retrospective (Paris: Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Palais du Louvre, Paris 1961), http://www.cmt-marktobey.net/Texts_from/texts_from.html