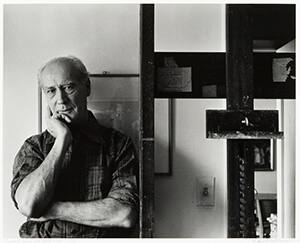

Lyonel Feininger

Some artists struggle to find their true identity. Are they illustrators or fine artists? Representational or abstract? Artists or craftsmen? For Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956), the situation was exacerbated: was he a musician or a painter? Was he a German or an American artist? After spending much of his life in Germany, Feininger returned to the city of his birth, New York, and reflected on his situation: “In Germany I was ‘der Amerikaner’; here in my native land I was sometimes classified and looked upon as a German painter…but what is the artist if not connected with the universe?” [1]

Feininger was born to musical parents; his father was a violinist and composer and his mother a singer and pianist. As a child, he drew illustrations and played at the sailboat pond in Central Park. At age sixteen, he gave a successful violin concert and went to Hamburg, Germany, to study music, which he soon abandoned. In 1888, he passed exams at the Royal Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, followed by a year in Liège, Belgium, where he studied French. In 1892, he spent six months at the academically traditional Atelier Colarossi in Paris before moving to Berlin. He supported himself by illustrations, mostly political caricatures and cartoons. During 1906 and 1907, he was employed by the Chicago Sunday Tribune which ran The Kin-der-kids and Wee Willie Winkie’s World in color on full pages. Living in Weimar, he met German Expressionists Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rotluff, and, in 1913, he exhibited with Der Blaue Reiter, an avant-garde group of Russian and German artists working in an expressionist vein.

Released from the draft because of his American citizenship, Feininger remained in Germany throughout World War I. Because artist materials were scarce, he turned to woodcuts marked by heavy dark lines and sharp angles. In 1919, he joined the newly founded Bauhaus and was placed in charge of the graphic workshop. He moved with the school to Dessau in 1926 and was appointed artist-in-residence without any regular teaching responsibilities. Feininger’s interest in photography blossomed in the mid-1920s and he built his own darkroom in 1928. When the Nazis forced the closure of the Bauhaus and confiscated 460 “degenerate” art works by Feininger, he decided to return to the United States. He taught summer courses at Mills College in Oakland, California, and in 1945 at Black Mountain College near Asheville, North Carolina, where he reconnected with fellow teachers from the Bauhaus, Josef Albers and Walter Gropius. In 1944, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, mounted a major exhibition of work by Feininger, which traveled to ten cities.

During his years in Germany, Feininger transitioned from being an illustrator to achieving his goal of becoming a fine artist. His affiliation with the Bauhaus made such modernists as Albers, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee his colleagues, but perhaps the most lasting influence on his art was Cubism, which he discovered in 1911. He recalled, “In the spring I had gone to Paris and the found the world agog with Cubism—a thing I have never heard even mentioned before. … I saw the light. ‘Cubism’—‘Form’ I should rather say—to which Cubism showed the way. Afterward it was amazing to find that I had been on the right road.” [2]

Translucency and overlapping planes characterize Feininger’s mature work, which usually portrayed buildings or seascapes. The mood is typically quiet and conveys both spirituality and musicality. According to Feininger’s son, “It is not too much to say that the light which informs Lyonel Feininger’s work is expression of an inner light as much as it is a translation into visual terms of an outer atmospheric event.” [3] He sought solitude, and one of his favorite places was the beach at Deep, on the Pomeranian coast of the Baltic Sea, where he would retreat without the distractions of friends and family. He also returned to his childhood interest in music, prompted perhaps by the role music played in the social life of the Bauhaus, and in 1921 composed several fugues for organ. Unlike his friends Albers and Kandinsky, who pursued abstraction, Feininger remained a representational artist. When invited by American Abstract Artists to join their group, he replied, “My artistic faith is founded on a deep love of nature, and all I represent or have achieved is based on this love.” [4]

Notes:

[1] Feininger quoted in Alois Schardt and Alfred H. Barr, Jr. Lyonel Feininger (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1944), 13, quoted in Barbara Haskell, et al, Lyonel Feininger: At the Edge of the World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press in association with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 2011), 154.

[2] Feininger to Alfred Vance Churchill, March 13, 1913, Archives of American Art, quoted in Haskell, Lyonel Feininger , 48.

[3] T. Lux Feininger, Lyonel Feininger: City at the Edge of the World (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1965), 19.

[4] Feininger, quoted in June L. Ness, ed., Lyonel Feininger (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1974), 61.