Roy Lichtenstein

At fourteen years of age, Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997) was taking art classes at the Parsons School of Design in his native New York City. Because his high school did not offer art classes, he enrolled in Saturday classes at the Art Students League, where his first class was with Reginald Marsh. Lichtenstein went on to Ohio State University, but his course of study was interrupted when he was drafted to serve in World War II. In 1946, he returned to the university to complete his Bachelor of Fine Arts, and, in 1949, he received his Master of Fine Arts. One of his instructors, Hoyt Sherman, had a distinctive teaching method for drawing based on psychological optics. The class met in the flash lab, a darkened space in which Sherman projected slides rapidly, and students had to draw based on their immediate recall of the images. Lichtenstein stayed on to teach at Ohio State University until 1951. When he was denied tenure, he and his wife, an interior designer, moved to Cleveland for her job. For the next six years, Lichtenstein made and exhibited art and worked various jobs, including commercial art and window displays for a department store. He traveled to New York regularly during this period, even going to the Cedar Bar, but he did not interact with the Abstract Expressionist artists who frequented the place, despite the fact that he was working in a similar manner.

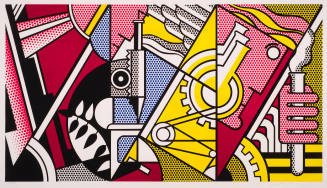

In 1957, Lichtenstein got a teaching position at the State University of New York at Oswego, before moving on to Rutgers University, where he taught at Douglass College from 1960 to 1964. At Rutgers, Lichtenstein became friends with Allan Kaprow and, through him, met other artists including Claes Oldenburg and Jim Dine, who were involved with the first Happenings of the early 1960s. Lichtenstein exhibited in group shows earlier in his career, but true fame came in 1961, shortly after he began using comic strip imagery. He got people’s attention by incorporating text and benday dots, a commercial printing process for adding shaded or tinted areas made up of dots. By the time of the seminal Pop art exhibition New Painting of Common Objects, held at the Pasadena Art Museum the following year, Lichtenstein had become one of the most recognized practitioners of the movement. Lichtenstein, along with Andy Warhol, is still foremost in any discussion of Pop art.

Roy Lichtenstein gained renown as a Pop artist when he was in his forties, but his style and subject matter continued to evolve. While his early work was abstract and he owed a debt to Cubism, his trademark style relates to modernist formalism, particularly in his use of primary colors and patterned shapes. His subject matter is unmistakably American in its thematic and stylistic references to popular culture of the post-World War II era.

Some critics considered his work facile and overtly commercial; nevertheless, Lichtenstein consistently worked in his Pop idiom, presenting a variety of subjects, including landscapes and a history of twentieth-century art. By depicting Picasso, Monet, or Matisse, or the brush strokes of Abstract Expressionism in his trademark style, Lichtenstein both satirized and paid homage to the Old Masters and some of his “blue chip” contemporaries. In the 1970s, Lichtenstein combined his usual techniques with collage to create Chinese landscapes, and over the years continued to explore different media such as ceramics, sculpture, enameled steel, and glass. The artist appeared in documentary films, contributed posters for entertainment events and political campaigns, and amiably lent himself to a variety of public events.

Lichtenstein came to prominence during a time when America was losing its provincialism and becoming hip and worldly. His art was in tune with the 1960s, and he himself was quite at home with a new degree of visibility—a casual semi-celebrity—that was starting to be conferred, or inflicted, upon certain up-and-coming artists. He is generally acknowledged as one of a handful of American artists that changed the direction of postwar art.