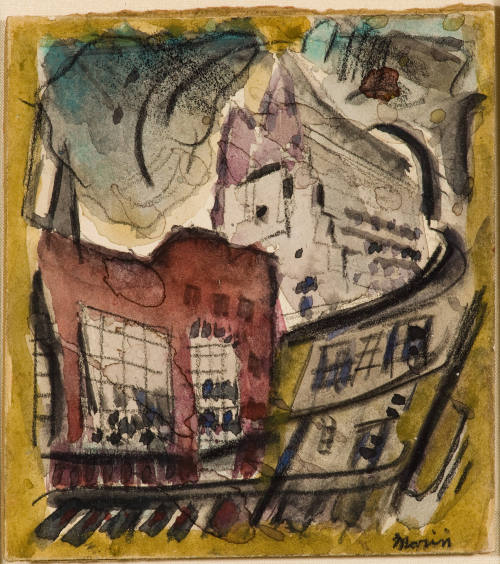

Skip to main contentBiographyAmerican artists working in the early decades of the twentieth century responded to both spectacular urban growth and European Modernism. In paintings and etchings, John Marin (1870–1953) exemplified this trend in an individualistic style that synthesized the fragmented space of Cubism with his considerable talent as a draughtsman.

A native of New Jersey, Marin was a late starter as an artist; he pursued mechanical drawing for a semester at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, and worked in architects’ offices until his late twenties. From 1899 to 1901, he studied with Thomas Anshutz and Hugh Breckenridge at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, followed by two years at the Art Students League in New York. In 1905, he moved to Paris where he remained for the next five years, traveling extensively in Europe and returning only once to America for a short interval. He dedicated himself to etching, producing over his lifetime approximately 180 prints, almost all carefully inked by Marin himself. In notes for an autobiography, Marin recalled his years in Paris:

4 years abroad

played some billiards

incidentally knocked out some

batches of etchings which people

rave over everywhere [1]

In addition to playing billiards, Marin regularly visited museums and exhibitions, but did not frequent Gertrude Stein’s soirées. He interacted with other expatriate American artists and was selected for inclusion in two prestigious exhibitions, the Salon d’Automne of 1907, which featured a retrospective of Paul Cézanne, and the Salon d’Automne of 1908, where paintings by Henri Matisse and other Fauvists were abundantly exhibited. While in Paris he met photographer and modern art promoter Alfred Stieglitz, who would remain a lifelong friend. In early 1910, Stieglitz mounted an exhibition of Marin’s watercolors, pastels, and etchings at his gallery 291, where he exhibited work by European and American avant-garde artists.

In fall 1910, Marin returned to the United States, living at times in Brooklyn and New Jersey. During summers, he sought out cooler destinations, and in 1914 he began to spend time along the coast of Maine, which would become his summer retreat later in life. With Stieglitz’s backing, Marin gained wide support and patronage for his paintings, which he produced in prodigious numbers. In addition to etchings, he was a prolific and proficient watercolorist. Ten of his watercolors were included in the famous Armory Show of 1913, considered a watershed exhibition that introduced American audiences to European Modernism. Marin also worked in oil, often designing his own frames, or painting frames within frames, for both his watercolors and oils.

In 1929, Mabel Dodge Luhan invited Marin to Taos, New Mexico, which had already been discovered by Stuart Davis, Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and others. They were equally enthralled with the landscape and culture of the Southwest. Marin spent two summers there, producing over one hundred watercolors. In 1936, he was the first artist to receive a retrospective in all media at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and in 1948, Look magazine named him “America’s number one artist.” This stature was affirmed by Clement Greenberg, the noted critic and champion of the Abstract Expressionists, who stated: “John Marin has the reputation, earned over the course of forty years, of being the greatest living American painter. He is certainly one of the best artists who ever handled a brush in this country.” [2] Marin’s tremendous facility with paint is often remarked upon and relates to his phenomenal productivity. Late in his career he rationalized his compulsion to paint:

I have to paint pictures—Oh yes I have to—Some cuss inside me forces me to paint—those things they call pictures—The thing to do is paint the perfect picture then you are through—you don’t have to paint—more—

One would be a damn fool to do so—

The startling things that can occur on a canvas

—the adventures— [3]

His writing style, both in his notes and correspondence, verged on poetry, fluid with stream of consciousness, not unlike the flowing nature of his art.

Notes:

[1] Marin, “Notes (Autobiographical),”Manuscripts 2 (March 1922), 5, quoted in Ruth E. Fine, John Marin (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1990), 76.

[2] Greenberg, quoted in James Cuno, foreword, John Marin’s Watercolors: A Medium for Modernism (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2010), 7.

[3] Marin to Charles Duncan, late September/early October 1948, John Marin archives, quoted in Cleve Gray, ed., John Marin by John Marin (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1977), 167.

John Marin

1870 - 1953

A native of New Jersey, Marin was a late starter as an artist; he pursued mechanical drawing for a semester at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, and worked in architects’ offices until his late twenties. From 1899 to 1901, he studied with Thomas Anshutz and Hugh Breckenridge at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, followed by two years at the Art Students League in New York. In 1905, he moved to Paris where he remained for the next five years, traveling extensively in Europe and returning only once to America for a short interval. He dedicated himself to etching, producing over his lifetime approximately 180 prints, almost all carefully inked by Marin himself. In notes for an autobiography, Marin recalled his years in Paris:

4 years abroad

played some billiards

incidentally knocked out some

batches of etchings which people

rave over everywhere [1]

In addition to playing billiards, Marin regularly visited museums and exhibitions, but did not frequent Gertrude Stein’s soirées. He interacted with other expatriate American artists and was selected for inclusion in two prestigious exhibitions, the Salon d’Automne of 1907, which featured a retrospective of Paul Cézanne, and the Salon d’Automne of 1908, where paintings by Henri Matisse and other Fauvists were abundantly exhibited. While in Paris he met photographer and modern art promoter Alfred Stieglitz, who would remain a lifelong friend. In early 1910, Stieglitz mounted an exhibition of Marin’s watercolors, pastels, and etchings at his gallery 291, where he exhibited work by European and American avant-garde artists.

In fall 1910, Marin returned to the United States, living at times in Brooklyn and New Jersey. During summers, he sought out cooler destinations, and in 1914 he began to spend time along the coast of Maine, which would become his summer retreat later in life. With Stieglitz’s backing, Marin gained wide support and patronage for his paintings, which he produced in prodigious numbers. In addition to etchings, he was a prolific and proficient watercolorist. Ten of his watercolors were included in the famous Armory Show of 1913, considered a watershed exhibition that introduced American audiences to European Modernism. Marin also worked in oil, often designing his own frames, or painting frames within frames, for both his watercolors and oils.

In 1929, Mabel Dodge Luhan invited Marin to Taos, New Mexico, which had already been discovered by Stuart Davis, Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and others. They were equally enthralled with the landscape and culture of the Southwest. Marin spent two summers there, producing over one hundred watercolors. In 1936, he was the first artist to receive a retrospective in all media at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and in 1948, Look magazine named him “America’s number one artist.” This stature was affirmed by Clement Greenberg, the noted critic and champion of the Abstract Expressionists, who stated: “John Marin has the reputation, earned over the course of forty years, of being the greatest living American painter. He is certainly one of the best artists who ever handled a brush in this country.” [2] Marin’s tremendous facility with paint is often remarked upon and relates to his phenomenal productivity. Late in his career he rationalized his compulsion to paint:

I have to paint pictures—Oh yes I have to—Some cuss inside me forces me to paint—those things they call pictures—The thing to do is paint the perfect picture then you are through—you don’t have to paint—more—

One would be a damn fool to do so—

The startling things that can occur on a canvas

—the adventures— [3]

His writing style, both in his notes and correspondence, verged on poetry, fluid with stream of consciousness, not unlike the flowing nature of his art.

Notes:

[1] Marin, “Notes (Autobiographical),”Manuscripts 2 (March 1922), 5, quoted in Ruth E. Fine, John Marin (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1990), 76.

[2] Greenberg, quoted in James Cuno, foreword, John Marin’s Watercolors: A Medium for Modernism (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2010), 7.

[3] Marin to Charles Duncan, late September/early October 1948, John Marin archives, quoted in Cleve Gray, ed., John Marin by John Marin (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1977), 167.

Person TypeIndividual