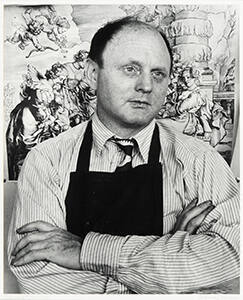

Reginald Marsh

Many artists of the early twentieth century turned to urban life as their primary subject matter. Like the Ashcan School artists a generation earlier, Reginald Marsh (1898–1954) drew inspiration from the energetic city life around him and reportedly said, “Well-bred people are no fun to paint.” [1] Marsh made a career of depicting the working girls, bums, and drunks in his Greenwich Village neighborhood; movie theaters and dance marathons; the rowdy crowds at Coney Island; and the striptease dancers and chorus girls in burlesque halls. “I felt fortunate indeed to be a citizen of New York, the greatest and most magnificent of all cities in a new and vital country whose history had scarcely been recorded in art. … New York City was in a period of rapid growth, its skyscrapers thrilling by growing higher and higher. There was a wonderful waterfront with tugs and ships of all kinds and steam locomotives on the Jersey shore. In and around were dumps, docks and slums, all wonderful to paint and in the city, subways, people, and burlesque shows.” [2]

Marsh was born in Paris, the son of two American artists. His father, Fred Dana Marsh, was an academic painter in the style of John Singer Sargent and a member of the National Academy of Design. When Marsh was a child, the family returned to the United States, settling in Nutley, New Jersey, a town popular with artists and writers. The family was supported in part by the fortune Marsh’s grandfather had made in the stockyards of Chicago, and the artist grew up enjoying seaside vacations, private schools, and, later, a comfortable inheritance. He attended Yale University, studying art but finding his most fulfilling creative outlet illustration work for The Yale Record. [3]

After graduating in 1920, Marsh moved to New York, working first as an illustrator for the New York Daily News and eventually for the fledgling publication The New Yorker. He also took classes at the Art Students League, studying with John Sloan and Kenneth Hayes Miller. The latter was particularly influential for the young artist; years later, Marsh would claim that he still showed Miller everything that he painted. [4]

In 1923, Marsh married Betty Burroughs, the daughter of a former curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The couple relocated to the Burroughs’s family home in Flushing, New York; with the move, Marsh solidified his place as part of an elite artistic community. [5] Two years later, he returned to Europe for the first time since childhood, traveling to Paris and reveling in the paintings of the old masters. His interest in classical anatomy grew more intense as a result of his travels and study.

When Marsh returned to New York, he took up painting in earnest for the first time and returned to his studies with Kenneth Hayes Miller. He was never comfortable in oil, declaring his work in the medium an “incoherent pasty mess.” His discovery of egg-based tempera paint in 1929, he later said, opened up a whole new world for him. [6] A gifted draftsman who reportedly drew constantly, filling hundreds of notebooks with sketches, Marsh also began making prints in the mid-1920s, both etchings and lithographs.

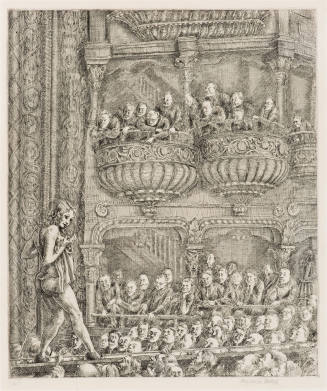

Marsh’s main subject matter had always been the characters that inhabited the city around him. When, in 1929, he began renting studio space on 14th Street, along with Miller, Isabel Bishop, Raphael Soyer, and others, he immersed himself in the vibrant and sometimes sordid life of Greenwich Village. His crowded images reflect the environment of the city itself, teeming with people and rife with details—signs, lampposts, buildings, hats, and dresses. Sent by Frank Crowninshield to sketch Coney Island for Vanity Fair, Marsh discovered for the first time the rich visual potential of the beach and the amusement park, and he returned to the place over and over again during the course of his career. [7] Burlesque halls were another frequent haunt; according to art historian Kathleen Spies, Marsh devoted over a third of his oeuvre to the subject. [8] He depicted all aspects of the dance halls—the dancers, alone or in groups; the leering audiences; the profusion of architectural details of the halls themselves. Although his style might generally be described as realism, he exaggerated the thighs, hips, buttocks, and breasts of his figures in a hyperrealist, near-Mannerist vein.

By 1930, Marsh had secured permanent gallery representation with the Frank K.M. Rehn Gallery and was beginning to achieve marked success in the art world. His work was well received by the critics; the Whitney Museum of Art was one of the first to acquire his paintings. In the mid-1930s, he began to teach at the Art Students League, accepting a semi-permanent post on the faculty by 1942. He was selected in 1935 by the U.S. Treasury Department to paint two murals in the Post Office Building in Washington, DC, depicting the activities of the postal workers and, in 1937, to create a series of murals in the rotunda of the United States Customs House in New York representing the various stages of a ship arriving in the port of New York. In 1937, he was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design, and a full Academician by 1943. His book Anatomy for Artists was published in 1945.

Marsh’s first marriage ended in divorce in 1933; less than a year later he married Felicia Meyer, a fellow artist, and began spending weekends and summers at her family home in Dorset, Vermont. Throughout the course of his career, he continued to travel and to experiment with different media: tempera, watercolor, etching, lithography, pen-and-ink, Chinese wash, and even a return to oil paint. Known by his friends for his competitive and active nature, Marsh died suddenly in Dorset of a heart attack in 1954.

Notes:

[1] Marsh, quoted in Ellen Wiley Todd, The “New Woman” Revised: Painting and Gender Politics on Fourteenth Street (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993), 180.

[2] Lloyd Goodrich, Reginald Marsh (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1972), 34.

[3] Goodrich, Reginald Marsh, 20.

[4] Goodrich, Reginald Marsh, 30.

[5] Todd, The “New Woman” Revised, 51.

[6] Goodrich, Reginald Marsh, 30 and 33.

[7] Todd, The “New Woman” Revised, 49.

[8] Kathleen Spies, “Girls and Gags: Sexual Display and Humor in Reginald Marsh’s Burlesque Images,” American Art (18, no. 2, Summer 2004), 34.