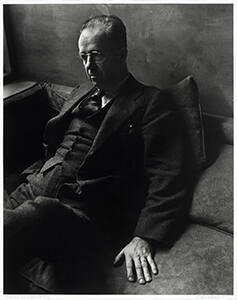

Charles Ephraim Burchfield

Not all artists fit neatly into the categories established by critics and used in textbooks on American art. Instead, some follow their own inner voices, which was the case with Charles E. Burchfield (1893–1967). While many of the paintings from his middle period, 1921–1943, might be labeled “American Scene” for their portrayals of small towns and industrial settings, they stand apart because of their underlying moodiness and expressive content. His depictions of nature, which frequently incorporate his carefully worked out symbols, hover between abstraction and realism. The artist himself chafed when people tried to pigeonhole him, and in 1938 he asserted: “I am not an Ohio, or western New York artist, but an American—or should I say an artist who happens to be born, living, painting in America.” [1]

A man who preferred to isolate himself, Burchfield lived most of his life in small towns in Ohio and upstate New York. He was born in Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio, and moved as a child to Salem, a modest town south of Youngstown. Growing up, he doodled, collected butterflies, and expected to become a naturalist. Later, he reflected on his childhood: “It seems to me I doodled all my life. I recall doodling on my mother’s Sunday tablecloth before I was of grade-school age. Perhaps I was born with a doodle pencil in my hand, the left one, in the same manner that a fortunate man is said to be born with a silver spoon in his mouth.” [2] Burchfield graduated from high school as the class valedictorian, and from 1912 to 1916 attended the Cleveland School of Art, where his concentration was in illustration. He was awarded a scholarship at the National Academy of Design, but left after one day, remaining in New York for a few weeks exploring museum collections, especially those of Oriental art. Burchfield then returned to Salem, supporting himself by odd jobs, and dedicated himself to his art.

In 1917, he created his Conventions for Abstract Thoughts, small, quick sketches or caricatures of thoughts and moods. He explained his inspiration: “Due to my ‘discovery’ of Chinese art, I determined to formulate a set of conventions, based on Nature, as other great artists had done, except that mine were to be completely my own.” [3] These invented symbols included such passions as fear, morbidness, insanity, imbecility, melancholy, nostalgia, dangerous brooding—many of the dark emotions Burchfield regularly felt. He later called 1917 his “Golden Year,” and produced more than two hundred paintings that served as the basis for themes he later developed. The curling and wavy lines of the Conventions became hallmarks of his style, bringing to life inanimate things like Victorian houses.

During a short stint in the United States army, Burchfield was assigned to the camouflage unit at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, one of the few times he ventured far from the shores of Lake Erie. Despite sporadic exhibitions and sales of his work, Burchfield worried about supporting himself, so in 1921 he took a position at M.H. Birge & Sons in Buffalo, where he designed wallpapers for the next eight years. He soon married and in 1925 purchased a house in Gardenville, a hamlet on the outskirts of Buffalo, which would remain his home until his death forty-two years later.

Whether painting townscapes or landscapes, Burchfield developed a distinctive style often based on his Conventions for Abstract Thoughts. His buildings and his insects look as if they have faces, and many paintings seem like visualizations of sounds. Burchfield enjoyed classical music and was particularly partial to compositions by Jean Sibelius. He was well read in American literature, preferring authors who shared his passion for nature and small towns: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Sherwood Anderson, and Sinclair Lewis. While he remained on good terms with his teachers from Cleveland, he had few links to the New York art world, with the exception of Edward Hopper. Burchfield and Hopper admired each other’s work, Hopper wrote an article on his friend, and they shared the same New York dealer, Frank Rehn.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Burchfield painted oils and watercolors of his surroundings in Buffalo, many featuring Gothic and Victorian architecture or desolate-looking factories. Browns and blacks dominated his palette during this period, and he frequently painted storms and snow scenes. Liberated by the reality that few people were buying art during World War II, about 1943 he began to focus almost exclusively on watercolor, and his work took a new direction in which nature was dominant. Long considering himself an agnostic and generally disdainful of organized religion, Burchfield was a virtual pantheist—although he disliked the term—in his approach to nature. Nevertheless, he joined the Lutheran church about this time, largely to please his wife.

From the age of sixteen until nine months before his death, he kept extensive journals—seventy-two volumes, ten thousand words—which often reflected his mood swings from the “blues” to exhilarated periods of great activity. He was also a profuse correspondent; in a 1945 letter to his dealer he confesses his self-doubt: “I have just gone through a period of about the worst blues in regard to my painting I have ever had. Absolutely sunk. I not only doubted the value of things I have been doing, but my worth as an artist, and wondered if I ever wanted to paint again.” [4]

Nostalgia often motivated Burchfield, as he stated in his journal: “Most terrible longings for my old life have assailed me tonight. I have unpacked some of my old sketches—the record of a burning stump, a brook falling over a pile of stones in a hollow, and huge buttonwoods lit up at sunset time.” Later, in the 1940s, these sketches became fodder for new paintings; he used them as the foundation of larger compositions to which he glued additional sheets of papers. This growing tendency toward enlargement, along with greater expressionism and freedom of brushwork, mirrors the aesthetic direction of the Abstract Expressionists during the late 1940s and 1950s. A comment in Burchfield’s journal in 1952 even suggests a kinship to their methods: “The subconscious mind seemed to be in complete control—and I did unpremeditated things which later turned out to be exactly right.” [5]

Notes:

[1] Burchfield to Frank Rehn, October 11,1938, as quoted in John I. H. Baur, The Inlander: Life and Work of Charles Burchfield, 1893–1967 (East Brunswick, NJ: Associated University Presses, Inc., and Cornwall Books, 1982), 168–169.

[2] Burchfield, “The Place of Drawing in an Artist’s Works,” in Edith H. Jones, ed., The Drawings of Charles Burchfield (New York: Frederick A. Praeger in association with the Drawing Society, 1968), quoted in Tullis Johnson, “A Seemingly Idle Diversion: The Doodles of Charles Burchfield,” in Cynthia Burlingham and Robert Gober, eds. Heat Wave in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield (Los Angeles, CA: Hammer Museum, University of California, and Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2099), 36.

[3] Burchfield, “Fifty Years as a Painter,” in Charles Burchfield: His Golden Year—A Retrospective Exhibition of Watercolors, Oils, and Graphics, organized by William Steadman (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1965), 15, quoted in Nancy Weekly, “Conventions for Abstract Thoughts,” in Burlingham and Gober, eds., Heat Wave in a Swamp, 22.

[4] Burchfield to Frank Rehn, July 3, 1945, quoted in Baur, The Inlander, 241.

[5] Burchfield, journal entry, February 15, 1922, quoted in Baur, The Inlander, 126, and journal entry, July 11, 1952, quoted in Burlingham and Gober, eds., Heat Wave in a Swamp, 92.