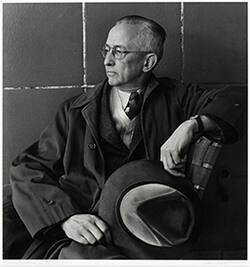

Skip to main contentBiography“Visionary” and “pioneer” are terms that apply to early American modernists and to one of their greatest supporters, Alfred Stieglitz. At his revolutionary gallery known as 291 for its address on Fifth Avenue, the photographer and gallerist showed the avant-garde work of Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin, and Pablo Picasso as well as that of their American counterparts John Marin, Alfred Maurer, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Marsden Hartley (1877–1943). Hartley’s affiliation with Stieglitz was one of the longest, lasting twenty-eight years from 1909 until 1936, and, in addition to serving as the painter’s dealer, Stieglitz provided financial and emotional sustenance in a relationship often filled with tension.

Hartley was born in Lewiston, Maine, a gritty mill town, where his early childhood was dispirited. His mother died when he was eight years old, which led to his living with an older sister in nearby Auburn. At sixteen the youth joined his father and stepmother in Cleveland, Ohio, where he took some art lessons from a local painter, John Semon. In 1898 he enrolled at the Cleveland School of Art with a full scholarship, but left after a year to study in New York at the William Chase School. In 1900 he transferred to the National Academy of Design, where he studied for four more years.

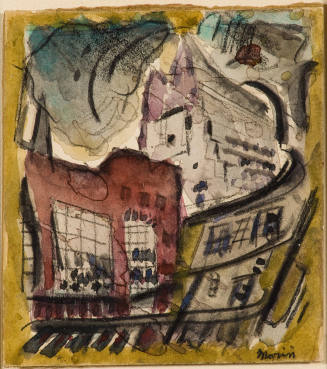

Throughout his life, Hartley was peripatetic, rarely remaining in one place for more than a ten-month period, sometimes in almost total isolation and at others immersing himself in cosmopolitan society. Similarly, his paintings embrace a broad range of styles and themes from synthetic cubism and poetic still lifes to impressionistic and expressionist landscapes. Part of Hartley’s restlessness may be attributed to his homosexuality, which led to his admiration for the poet Walt Whitman and deep attachments to artist Charles Demuth, a young German army officer named Karl von Freyburg, and athletic young fishermen in Nova Scotia.

In spring 1912 Hartley traveled abroad for the first time. In Paris he quickly became part of the artistic community, frequently visiting the salons hosted by Gertrude Stein and gaining her patronage. The following year he went to Berlin and Munich where he met Wassily Kandinsky. In a letter to fellow painter Rockwell Kent, he explained: “Personally, while I do not altogether dislike the French I turn to the Germans with more alacrity for they are more sturdy like ourselves.” [1] Hartley was largely based in Berlin until 1915, although he occasionally crossed the Atlantic to manage his affairs and to organize exhibitions. The body of work associated with this period is among his best known and includes many colorful, cubist-inspired, and symbol laden canvases, many of which celebrated his devotion to von Freyburg.

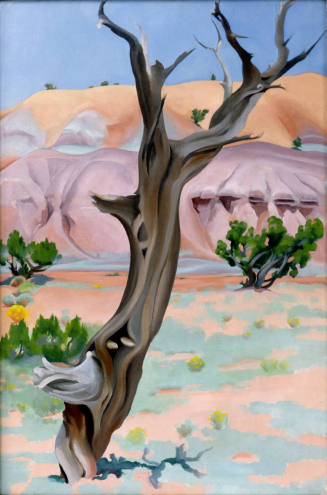

Under the influence of the German interest in the primitive, Hartley painted a series that employed Native American motifs, such as teepees, bowls, baskets, canoes and campfires. Describing his passion he wrote to Stieglitz: “I find myself wanting to be an Indian—to paint my face with the symbols of that race I adore, to go to the West and face the sun forever—that would seem the true expression of human dignity.” [2] Hoping to maximize this interest, in 1918 Hartley went to Santa Fe and Taos, but was disillusioned by the modern lifestyle of the Native Americans who were driving cars rather than paddling canoes. He turned instead to the landscape and completed a series of lyrical pastels; later he painted the terrain from memory.

In 1921, Hartley intended to move to Germany permanently, but became disenchanted. This led to a period of itinerancy, which included time spent in New York, Vence and Aix-en-Provence, Hamburg, Dresden, Paris, and a year in Mexico on a Guggenheim fellowship. While in southern France he painted a series of Mont-Ste-Victoire, the mountain immortalized by Paul Cézanne, which looked back to Hartley’s views of New Mexico and forward to his paintings of Mount Katahdin in Maine. In these paintings he tended to emphasize the strong profiles of the mountains and hills and diminished the foregrounds.

Hartley frequently suffered dry spells when he could not paint for emotional and financial reasons. During these he often turned to writing, both poetry and art criticism, although he declared “A true art needs no speech—it speaks itself.” [3] In addition to writing for prestigious journals such as Stieglitz’s Camera Work, Dial, and Nation, in1921 he published Adventures in Art, which consisted of seventeen essays. He maintained that neither journalists nor art historians made fit critics. Prompted by Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, he began his own autobiography, Somehow a Past in 1933, put it aside for a while, and finally returned to it in 1938.

Like many artists, Hartley often lived in meager, if not dire, circumstances, and as a result his health was compromised. For short intervals he participated in the easel program of the Public Works of Art Project. Despite bleak memories of his early years, Hartley made Maine his home for the last years of his life. Not wanting to be labeled an “expatriate” and aspiring to join the rising tide of regionalism, he worked assiduously on paintings of New England. Several compelling series—coastal landscapes, views of Katahdin and figurative paintings of fishermen—finally brought him some recognition and a little security. His dealer from 1938 to 1940, Hudson Walker, purchased twenty-three paintings for $5,000; many of these are at the Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota.

Toward the end of his life, Hartley wrote prophetically, “I am not a ‘book of the month’ artist and do not paint pretty pictures; but when I am no longer here my name will register forever in the history of American art and so that’s something too.” [4] For many decades, Hartley’s reputation was eclipsed, but in the 1980s serious scholarship was undertaken and has continued as interest in gender studies and “local” artists has advanced.

Notes:

[1] Hartley to Kent, August 12, 1912, Rockwell Kent papers, Archives of American Art, quoted in Barbara Haskell, Marsden Hartley (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with New York University Press, 1980), 26.

[2] Hartley to Stieglitz, November 13, 1914, Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe Archive, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, quoted in Wanda M. Corn, “Marsden Hartley’s Native Amerika,” in Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, Marsden Hartley (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, CT: 2002), 69.

[3] Hartley to Stieglitz, June 13, 1913, Stieglitz/O’Keeffe Archive, quoted in Jonathan Weinberg, “Marsden Hartley: Writing on Paintings,” in Kornhauser, Marsden Hartley, 121.

[4] Hartley to Norma Berger, quoted in Bruce Robertson, Marsden Hartley (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1995), 9.

Marsden Hartley

1877 - 1943

Hartley was born in Lewiston, Maine, a gritty mill town, where his early childhood was dispirited. His mother died when he was eight years old, which led to his living with an older sister in nearby Auburn. At sixteen the youth joined his father and stepmother in Cleveland, Ohio, where he took some art lessons from a local painter, John Semon. In 1898 he enrolled at the Cleveland School of Art with a full scholarship, but left after a year to study in New York at the William Chase School. In 1900 he transferred to the National Academy of Design, where he studied for four more years.

Throughout his life, Hartley was peripatetic, rarely remaining in one place for more than a ten-month period, sometimes in almost total isolation and at others immersing himself in cosmopolitan society. Similarly, his paintings embrace a broad range of styles and themes from synthetic cubism and poetic still lifes to impressionistic and expressionist landscapes. Part of Hartley’s restlessness may be attributed to his homosexuality, which led to his admiration for the poet Walt Whitman and deep attachments to artist Charles Demuth, a young German army officer named Karl von Freyburg, and athletic young fishermen in Nova Scotia.

In spring 1912 Hartley traveled abroad for the first time. In Paris he quickly became part of the artistic community, frequently visiting the salons hosted by Gertrude Stein and gaining her patronage. The following year he went to Berlin and Munich where he met Wassily Kandinsky. In a letter to fellow painter Rockwell Kent, he explained: “Personally, while I do not altogether dislike the French I turn to the Germans with more alacrity for they are more sturdy like ourselves.” [1] Hartley was largely based in Berlin until 1915, although he occasionally crossed the Atlantic to manage his affairs and to organize exhibitions. The body of work associated with this period is among his best known and includes many colorful, cubist-inspired, and symbol laden canvases, many of which celebrated his devotion to von Freyburg.

Under the influence of the German interest in the primitive, Hartley painted a series that employed Native American motifs, such as teepees, bowls, baskets, canoes and campfires. Describing his passion he wrote to Stieglitz: “I find myself wanting to be an Indian—to paint my face with the symbols of that race I adore, to go to the West and face the sun forever—that would seem the true expression of human dignity.” [2] Hoping to maximize this interest, in 1918 Hartley went to Santa Fe and Taos, but was disillusioned by the modern lifestyle of the Native Americans who were driving cars rather than paddling canoes. He turned instead to the landscape and completed a series of lyrical pastels; later he painted the terrain from memory.

In 1921, Hartley intended to move to Germany permanently, but became disenchanted. This led to a period of itinerancy, which included time spent in New York, Vence and Aix-en-Provence, Hamburg, Dresden, Paris, and a year in Mexico on a Guggenheim fellowship. While in southern France he painted a series of Mont-Ste-Victoire, the mountain immortalized by Paul Cézanne, which looked back to Hartley’s views of New Mexico and forward to his paintings of Mount Katahdin in Maine. In these paintings he tended to emphasize the strong profiles of the mountains and hills and diminished the foregrounds.

Hartley frequently suffered dry spells when he could not paint for emotional and financial reasons. During these he often turned to writing, both poetry and art criticism, although he declared “A true art needs no speech—it speaks itself.” [3] In addition to writing for prestigious journals such as Stieglitz’s Camera Work, Dial, and Nation, in1921 he published Adventures in Art, which consisted of seventeen essays. He maintained that neither journalists nor art historians made fit critics. Prompted by Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, he began his own autobiography, Somehow a Past in 1933, put it aside for a while, and finally returned to it in 1938.

Like many artists, Hartley often lived in meager, if not dire, circumstances, and as a result his health was compromised. For short intervals he participated in the easel program of the Public Works of Art Project. Despite bleak memories of his early years, Hartley made Maine his home for the last years of his life. Not wanting to be labeled an “expatriate” and aspiring to join the rising tide of regionalism, he worked assiduously on paintings of New England. Several compelling series—coastal landscapes, views of Katahdin and figurative paintings of fishermen—finally brought him some recognition and a little security. His dealer from 1938 to 1940, Hudson Walker, purchased twenty-three paintings for $5,000; many of these are at the Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota.

Toward the end of his life, Hartley wrote prophetically, “I am not a ‘book of the month’ artist and do not paint pretty pictures; but when I am no longer here my name will register forever in the history of American art and so that’s something too.” [4] For many decades, Hartley’s reputation was eclipsed, but in the 1980s serious scholarship was undertaken and has continued as interest in gender studies and “local” artists has advanced.

Notes:

[1] Hartley to Kent, August 12, 1912, Rockwell Kent papers, Archives of American Art, quoted in Barbara Haskell, Marsden Hartley (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with New York University Press, 1980), 26.

[2] Hartley to Stieglitz, November 13, 1914, Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia O’Keeffe Archive, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, quoted in Wanda M. Corn, “Marsden Hartley’s Native Amerika,” in Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, Marsden Hartley (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, CT: 2002), 69.

[3] Hartley to Stieglitz, June 13, 1913, Stieglitz/O’Keeffe Archive, quoted in Jonathan Weinberg, “Marsden Hartley: Writing on Paintings,” in Kornhauser, Marsden Hartley, 121.

[4] Hartley to Norma Berger, quoted in Bruce Robertson, Marsden Hartley (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1995), 9.

Person TypeIndividual