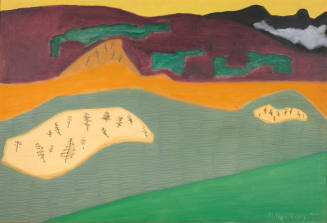

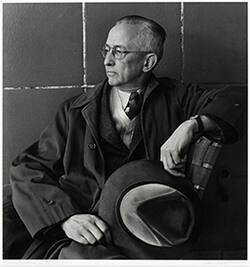

Skip to main contentBiographyAbstraction in America was fostered by such luminaries as Duncan Phillips and Alfred Stieglitz, and spearheaded by artists like Arthur Wesley Dow and Arthur Garfield Dove (1880–1946). Dove was consistently inspired by nature and developed symbols—or, as he termed them, extractions—which expressed nature’s essence rather than its recognizable form. His style is sometimes called biomorphic abstraction. In 1910 Dove created six paintings he called Abstraction which are recognized as the first nonrepresentational paintings produced in the United States, around the time that the Russian artist Wassily Kandinsky was doing the same thing in Germany. Dove belonged to the circle of artists befriended and promoted by artist and dealer Stieglitz; another important supporter and patron was Phillips, the art collector and museum founder. The Phillips Collection has the largest and most comprehensive collection of the artist’s works.

Born to a successful brick manufacturer and his wife in Canandaigua in the Finger Lakes region in upstate New York, Dove was raised in nearby Geneva. He attended Hobart University in his hometown for two years but finished his degree at Cornell University, where he undertook a pre-law course of study and also took art classes. After his 1903 graduation, Dove moved to New York City and was employed as an illustrator, working for Harper’s and Century, among other magazines. In 1904 he married a Geneva neighbor, Florence Dorsey. Dove’s father supported their eighteen-month trip in 1907 to Europe; later he would prove unsympathetic and disinherited his son when the latter chose to become an artist. While abroad, Dove painted mostly in southern France in an Impressionist style. He met the American artists Patrick Henry Bruce, Max Weber, and Alfred Maurer, with whom he became good friends. In 1909 he returned to the United States and took up illustration work again. With the birth of his only son, William, the following year, Dove decided to try farming in Westport, Connecticut, but he still pursued his art.

In 1910 he met Maurer’s dealer, the fine art photographer and art impresario Stieglitz, who included an oil painting by Dove in a group exhibition. Two years later Stieglitz gave the thirty-two year old Dove his first solo exhibition at the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, or “291,” as it became known, because of its location at 291 Fifth Avenue, New York. Stieglitz represented Dove for the rest of the dealer’s life. In 1934 Dove wrote about his mentor:

When asked what Stieglitz means to me as an artist, I answer: everything.

Because I value his opinion as one who has always known.

I do not think I could have existed as a painter without that super-encouragement and the battle he has fought day by day for twenty-five years.

He is without a doubt the one who has done the most for art in America. [2]

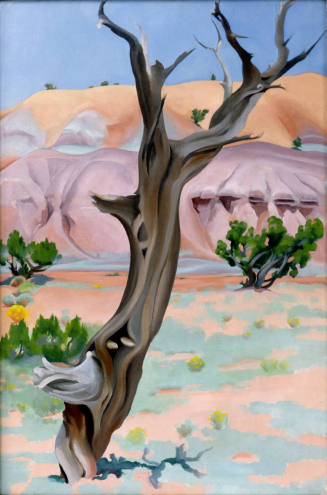

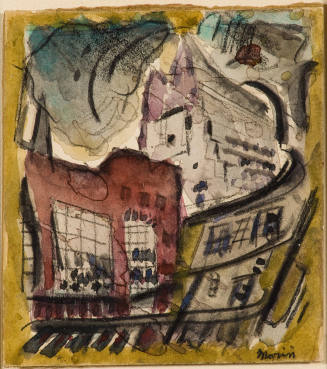

Stieglitz’s wife, the artist Georgia O’Keeffe, and Dove each admired and collected the other’s work and were often compared by contemporary critics. Dove and O’Keeffe, along with other young artists at the turn of the century, were greatly influenced by the ideas of art educator Arthur Wesley Dow and his influential work Composition, first published in 1899. Dow believed chiefly that art need not attempt to be an imitation of nature but rather that it develops from formal, abstract relationships. He also felt that visual art should be equivalent in expression to the pure, formal properties of music. Dove, along with Stieglitz, was deeply interested in the concept of synaesthesia, the direct and simultaneous association of specific colors in visual art to distinct musical sounds. Dove explained: “The line is the result of reducing dimension from the solid to the plane then to the point. A moving point could follow a waterfall and dance. We have the scientific proof that the eye sees everything best at one point. I should like to take wind and water and sand as a motif and work with them, but it has to be simplified in most cases to color and force lines and substances, just as music has done with sound.” [1]

By 1921, the Doves had separated, and he was in a relationship with the artist Helen Torr Weed, known as “Reds.” They acquired a forty-two foot yawl, the Mona, and lived and worked aboard this houseboat for seven years. This began a prolonged period of extreme privation for the couple but Reds shared Dove’s dedication to art. Limited by space and lack of funds for art supplies, Dove nevertheless produced drawings, pastels, watercolor and oil paintings as well as assemblages for annual exhibitions beginning in 1926 at Stieglitz’s Intimate Gallery and, after 1930, An American Place. Dove did not sell a painting until 1926; the buyer was Phillips. In 1930, Phillips began giving Dove a monthly stipend of fifty dollars for the right of first choice from his annual exhibition, an arrangement which annoyed Stieglitz, but for many years it was often the artist’s only predictable income.

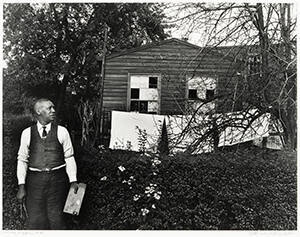

Like others in the Stieglitz circle, Dove chose not to work on the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration. The Doves left the Ketewomoke Yacht Club in Halesite, Long Island, where Dove had been caretaker from 1929 to 1933 in exchange for rent, and relocated to Geneva. There the couple would live first in one, then another farmhouse, living off the land, fixing up the houses to try to sell, eventually moving into the top floor of the Dove Block, a commercial building belonging to his family, located in the center of downtown Geneva. In the works produced during these five years, Dove’s art reflected his surroundings—the lakes, the farm and its livestock, even some of the industry, but not in a representational vein. By 1938, however, the Doves moved again, into a former post office in Centerport, Long Island. Dove’s health had been significantly weakened over the years by physical and psychological stress. He developed pneumonia and in January 1939, suffered a heart attack and was discovered to have Bright’s disease, a serious kidney disorder. In November 1946, he had another heart attack, which paralyzed half of his body. He died in a hospital in Huntington, Long Island, just four months after the death of his patron Stieglitz.

Notes:

[1] Dove, “A Different One,” America and Alfred Stieglitz: A Collective Portrait (New York: The Literary Guild, 1934), 245.

[2] Debra Bricker Balken, “Continuities and Digressions in the Work of Arthur Dove from 1907 to 1933,” in Arthur Dove: A Retrospective (Amherst, MA: Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA, and the MIT Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with the Phillips Collection, Washington DC, 1997), 33.

Arthur Dove

1880 - 1946

Born to a successful brick manufacturer and his wife in Canandaigua in the Finger Lakes region in upstate New York, Dove was raised in nearby Geneva. He attended Hobart University in his hometown for two years but finished his degree at Cornell University, where he undertook a pre-law course of study and also took art classes. After his 1903 graduation, Dove moved to New York City and was employed as an illustrator, working for Harper’s and Century, among other magazines. In 1904 he married a Geneva neighbor, Florence Dorsey. Dove’s father supported their eighteen-month trip in 1907 to Europe; later he would prove unsympathetic and disinherited his son when the latter chose to become an artist. While abroad, Dove painted mostly in southern France in an Impressionist style. He met the American artists Patrick Henry Bruce, Max Weber, and Alfred Maurer, with whom he became good friends. In 1909 he returned to the United States and took up illustration work again. With the birth of his only son, William, the following year, Dove decided to try farming in Westport, Connecticut, but he still pursued his art.

In 1910 he met Maurer’s dealer, the fine art photographer and art impresario Stieglitz, who included an oil painting by Dove in a group exhibition. Two years later Stieglitz gave the thirty-two year old Dove his first solo exhibition at the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, or “291,” as it became known, because of its location at 291 Fifth Avenue, New York. Stieglitz represented Dove for the rest of the dealer’s life. In 1934 Dove wrote about his mentor:

When asked what Stieglitz means to me as an artist, I answer: everything.

Because I value his opinion as one who has always known.

I do not think I could have existed as a painter without that super-encouragement and the battle he has fought day by day for twenty-five years.

He is without a doubt the one who has done the most for art in America. [2]

Stieglitz’s wife, the artist Georgia O’Keeffe, and Dove each admired and collected the other’s work and were often compared by contemporary critics. Dove and O’Keeffe, along with other young artists at the turn of the century, were greatly influenced by the ideas of art educator Arthur Wesley Dow and his influential work Composition, first published in 1899. Dow believed chiefly that art need not attempt to be an imitation of nature but rather that it develops from formal, abstract relationships. He also felt that visual art should be equivalent in expression to the pure, formal properties of music. Dove, along with Stieglitz, was deeply interested in the concept of synaesthesia, the direct and simultaneous association of specific colors in visual art to distinct musical sounds. Dove explained: “The line is the result of reducing dimension from the solid to the plane then to the point. A moving point could follow a waterfall and dance. We have the scientific proof that the eye sees everything best at one point. I should like to take wind and water and sand as a motif and work with them, but it has to be simplified in most cases to color and force lines and substances, just as music has done with sound.” [1]

By 1921, the Doves had separated, and he was in a relationship with the artist Helen Torr Weed, known as “Reds.” They acquired a forty-two foot yawl, the Mona, and lived and worked aboard this houseboat for seven years. This began a prolonged period of extreme privation for the couple but Reds shared Dove’s dedication to art. Limited by space and lack of funds for art supplies, Dove nevertheless produced drawings, pastels, watercolor and oil paintings as well as assemblages for annual exhibitions beginning in 1926 at Stieglitz’s Intimate Gallery and, after 1930, An American Place. Dove did not sell a painting until 1926; the buyer was Phillips. In 1930, Phillips began giving Dove a monthly stipend of fifty dollars for the right of first choice from his annual exhibition, an arrangement which annoyed Stieglitz, but for many years it was often the artist’s only predictable income.

Like others in the Stieglitz circle, Dove chose not to work on the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration. The Doves left the Ketewomoke Yacht Club in Halesite, Long Island, where Dove had been caretaker from 1929 to 1933 in exchange for rent, and relocated to Geneva. There the couple would live first in one, then another farmhouse, living off the land, fixing up the houses to try to sell, eventually moving into the top floor of the Dove Block, a commercial building belonging to his family, located in the center of downtown Geneva. In the works produced during these five years, Dove’s art reflected his surroundings—the lakes, the farm and its livestock, even some of the industry, but not in a representational vein. By 1938, however, the Doves moved again, into a former post office in Centerport, Long Island. Dove’s health had been significantly weakened over the years by physical and psychological stress. He developed pneumonia and in January 1939, suffered a heart attack and was discovered to have Bright’s disease, a serious kidney disorder. In November 1946, he had another heart attack, which paralyzed half of his body. He died in a hospital in Huntington, Long Island, just four months after the death of his patron Stieglitz.

Notes:

[1] Dove, “A Different One,” America and Alfred Stieglitz: A Collective Portrait (New York: The Literary Guild, 1934), 245.

[2] Debra Bricker Balken, “Continuities and Digressions in the Work of Arthur Dove from 1907 to 1933,” in Arthur Dove: A Retrospective (Amherst, MA: Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA, and the MIT Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with the Phillips Collection, Washington DC, 1997), 33.

Person TypeIndividual