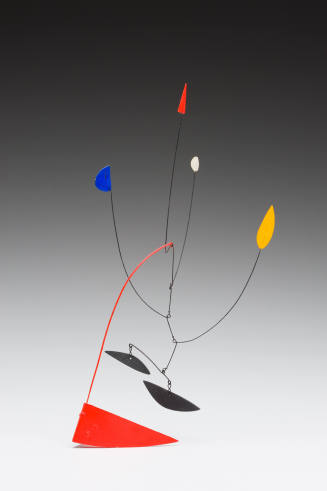

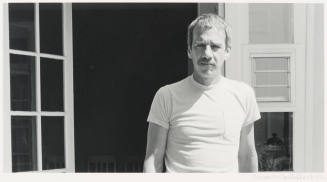

Skip to main contentBiographyInternationally regarded by artists and critics for his minimal sculptures and poems, Carl Andre (born 1935) has often been controversial. A 1972 exhibition in London created an uproar, as members of the public questioned the expenditure of public funds and vandalized his Equivalent VIII, an installation of 120 bricks arranged in a rectangle. His major contribution, however, has been to redefine the making of sculpture, moving it away from carving and casting toward the arrangement and placement of raw materials such as wood, bricks, and metal plates.

Andre was born in Quincy, Massachusetts, where his father was a marine draughtsman. They lived close to the naval yard, which likely instigated the artist’s fascination with steel plates. On scholarship at the prestigious Phillips Academy in nearby Andover from 1951 to 1953, he received his only formal art education. He enrolled at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, but left shortly afterward to travel in France and England. From 1955 to 1957 he served in the United States Army in North Carolina as part of an intelligence division. He then settled in New York and shared a studio with minimalist artist and former classmate Frank Stella. Stella was working on his black paintings at the time and introduced Andre to the work of Constantin Brancusi, the recently deceased European artist known for his sensitivity to materials and abstract sculptures.

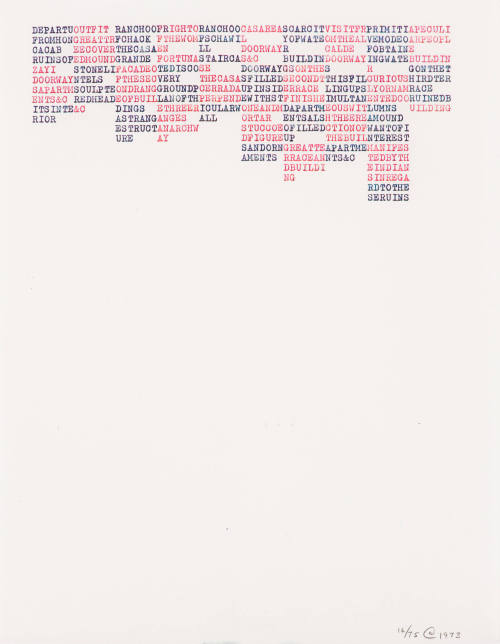

Reflecting on the start of his career, Andre recalled: “In the years when I was trying to get my work shown and accepted and so forth, I went to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad and that was my formal art school. You can learn a hell of a lot about sculpture, working in a railroad. The thing about getting a job outside of art is the fact that you can find out whole areas of materials. I don’t mean new ones. I mean old ones like scrap iron. A railroad is essentially a big collection of scrap iron, and that’s why it’s great.” [1] Inspired by the world around him, Andre began to make minimalist sculpture and write poems in the tradition of Concrete Poetry, which emphasizes the layout and look of a poem as much as the words. Not unhappy to be considered a minimalist, he also described himself more as a “matterist” because of his use of simple, often prefabricated materials. These he carefully arranges, insisting that he be directly involved with the initial installation out of concern for their relationship to their environment. He is most recognized for his floor compositions: square metal plates which are often overlooked by museum visitors.

In 1985, Andre’s life changed with the sudden death of his wife, Cuban artist Ana Mendienta, who fell from a window on the thirty-fourth floor of their apartment building. While Andre told police he was not in the room at the time, others claimed the couple had been arguing and he pushed her. After a highly publicized trial three years later, Andre was acquitted of murder.

At the Chinati Foundation—widely recognized as the “shrine to minimal art” established by fellow sculptor Donald Judd in rural Marfa, Texas—Andre is represented by a large installation of thirteen rows of steel plates. He denies any specific connection to his experience working on the railroad, or to the tracks running through town. Like his art, Andre is a man of few words who sets clear limits on himself and his work. “I have found set of solutions to a set of problems in sculpture, and I work within those parameters. But it is limits that give us possibilities. Without limits nothing really good can be accomplished. I feel I have been liberated by them.” [2]

Notes:

[1] Andre, quoted in Peggy Gale, ed., Artists Talks 1969–1977 (Nova Scotia, Canada: The Press N.S.C.A.D, 2004), 27.

[2] Randy Kennedy, “For Carl Andre, Less is Still Less,” New York Times, July 14, 2011.

Carl Andre

1935 - 2024

Andre was born in Quincy, Massachusetts, where his father was a marine draughtsman. They lived close to the naval yard, which likely instigated the artist’s fascination with steel plates. On scholarship at the prestigious Phillips Academy in nearby Andover from 1951 to 1953, he received his only formal art education. He enrolled at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, but left shortly afterward to travel in France and England. From 1955 to 1957 he served in the United States Army in North Carolina as part of an intelligence division. He then settled in New York and shared a studio with minimalist artist and former classmate Frank Stella. Stella was working on his black paintings at the time and introduced Andre to the work of Constantin Brancusi, the recently deceased European artist known for his sensitivity to materials and abstract sculptures.

Reflecting on the start of his career, Andre recalled: “In the years when I was trying to get my work shown and accepted and so forth, I went to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad and that was my formal art school. You can learn a hell of a lot about sculpture, working in a railroad. The thing about getting a job outside of art is the fact that you can find out whole areas of materials. I don’t mean new ones. I mean old ones like scrap iron. A railroad is essentially a big collection of scrap iron, and that’s why it’s great.” [1] Inspired by the world around him, Andre began to make minimalist sculpture and write poems in the tradition of Concrete Poetry, which emphasizes the layout and look of a poem as much as the words. Not unhappy to be considered a minimalist, he also described himself more as a “matterist” because of his use of simple, often prefabricated materials. These he carefully arranges, insisting that he be directly involved with the initial installation out of concern for their relationship to their environment. He is most recognized for his floor compositions: square metal plates which are often overlooked by museum visitors.

In 1985, Andre’s life changed with the sudden death of his wife, Cuban artist Ana Mendienta, who fell from a window on the thirty-fourth floor of their apartment building. While Andre told police he was not in the room at the time, others claimed the couple had been arguing and he pushed her. After a highly publicized trial three years later, Andre was acquitted of murder.

At the Chinati Foundation—widely recognized as the “shrine to minimal art” established by fellow sculptor Donald Judd in rural Marfa, Texas—Andre is represented by a large installation of thirteen rows of steel plates. He denies any specific connection to his experience working on the railroad, or to the tracks running through town. Like his art, Andre is a man of few words who sets clear limits on himself and his work. “I have found set of solutions to a set of problems in sculpture, and I work within those parameters. But it is limits that give us possibilities. Without limits nothing really good can be accomplished. I feel I have been liberated by them.” [2]

Notes:

[1] Andre, quoted in Peggy Gale, ed., Artists Talks 1969–1977 (Nova Scotia, Canada: The Press N.S.C.A.D, 2004), 27.

[2] Randy Kennedy, “For Carl Andre, Less is Still Less,” New York Times, July 14, 2011.

Person TypeIndividual