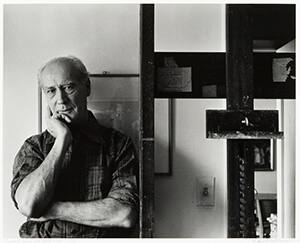

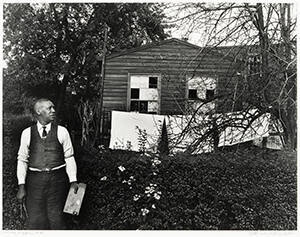

Skip to main contentBiographyMany twentieth-century artists were also political activists who embraced such issues as the environment, AIDS, and the rights of minorities. They made their art to catch the attention of the general public as well as politicians. One of the most outspoken of this ilk was German artist Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) whose practice included sculpture, installation, and performance art. Greatly influenced by the ideas of Rudolf Steiner, Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Schiller, James Joyce, and others, Beuys also taught art and art theory. He consistently promoted his concept of “Social Sculpture” in which all social activity is one great work of art that all can contribute to: “That is the idea of the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ in which EVERY HUMAN BEING IS AN ARTIST.” [1]

Beuys was born in Krefeld, Germany, raised in Kleve, and died in Düsseldorf. His early years coincided with the rise of Nazism; he was a member of the Hitler Youth and fought for Germany in World War II. As a young student Beuys had shown artistic promise in drawing, studied the piano and cello, and developed a strong interest in the natural sciences. One anecdote recounts that, in 1933, the teenage artist rescued a copy of Carl Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae when members of the Nazi Party had a book burning in the courtyard of his high school in Kleve. Whether or not this event actually took place, it establishes Beuys’s sense of himself as romantic, intellectual, and shamanistic, one with intense sensory recall, and one who rejected censorship and authoritarian regimes.

By the time he completed high school in spring 1941, Beuys had resolved to become a sculptor; however, he decided to join the Luftwaffe rather than being drafted. While training as an aircraft radio operator, he studied biology and zoology at the University of Poznan in Poland, which was then under German control. In 1942, Beuys was stationed in the Crimea as part of a dive-bomber unit, deploying as a rear gunner. In March 1944, he was gunned down and crashed. He was rescued, he later said, by “Tartars,” the nomadic Tatar tribesmen in the area. “I must have shot through the windscreen as it flew back at the same speed as the plane hit the ground and that saved me, though I had bad skull and jaw injuries. Then the tail flipped over and I was completely buried in the snow. That’s how the Tartars found me days later. I remember voices saying ‘Voda’ (water), then the felt of their tents, and the dense pungent smell of cheese, fat, and milk. They covered my body in fat to help it regenerate warmth, and wrapped it in felt as an insulator to keep warmth in.” [2] After recovering from his wounds he was sent back to the front in August. When Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, Beuys was sent to an internment camp in England, but by August he had returned to his parents’ home in Germany.

Following the war, Beuys resumed his art career; he studied at the Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts) between 1947 and 1953, studying with Ewald Mataré. He founded an artist society, the Donnerstag Gesellschaft (Thursday Group), with Hann Trier and other young artists in 1947 and they held exhibitions and programs through 1950. The 1950s were extremely difficult for Beuys, as he struggled with depression that, in retrospect, might have been post-traumatic stress disorder. Late in the decade he began to illustrate James Joyce’s Ulysses and this work, when completed in 1961, brought him critical attention. That same year he was given the position of Professor of Monumental Sculpture at his alma mater, the Kunstakademie, in Düsseldorf. Beuys was fired in 1972 because, among other things, he allowed anyone to attend his classes and had no requirements.

It was in Düsseldorf in 1962 that Beuys met the artist Nam June Paik, a member of the Fluxus movement comprised of avant-garde artists, musicians, and performance artists of different nationalities. As defined by its avowed leader, George Macunias, Fluxus productions “must appear to be complex, pretentious, profound, serious, intellectual, inspired, skillful, significant and theoretical.” [3] Through Paik, Beuys met the American musician and composer John Cage, for whom he had great admiration. Beuys was briefly associated with Fluxus but ultimately rejected their Dadaesque activities. He was more interested in negotiating societal change, blending his interests in science and spirituality, human creativity, and nature. He turned to installation and performance art to explore these interests.

Beuys represented Germany in the Venice Biennales of 1976 and 1980 and, in 1979, was given a one-man retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. A staunch pacifist and environmentalist, Beuys co-founded Germany’s Student Party in 1967, founded the Free International University in 1974, and was a co-founder of the Green Party in 1980. Beuys styled himself as an artist/shaman/educator/politician, and his cultural output encompassed performance pieces such as the seminal 1965 “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare,” the 1982 pop music video, “Sonne statt Reagan” (Sun, not Rain/Reagan), and “7000 Oaks: City Forestation Instead of City Administration” (1982–1987). For the first, Beuys smeared honey and gold leaf on his head and walked around his installation, murmuring indecipherably for three hours to the body of a dead hare he was holding. One of his last projects, “Oaks,” consisted of 7,000 four-foot tall black basalt markers paired with an equal number of oak trees planted throughout the city of Kassel, with the mission of encouraging individuals to effect eco-urbanization and environmental and social change on a global scale. Beuys died in Düsseldorf in January 1986, only a few years before the dismantling of the Berlin Wall, which the artist surely would have regarded as a quintessential Social Sculpture.

Notes:

[1] Beuys, “Artist’s statement,” in Zeitgest (New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1983), 82.

[2] Caroline Tisdall, Joseph Beuys (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1979), 16–17.

[3] Macunias quoted in Emmett Williams, My Life in Flux—and Vice Versa (London: Thames and Hudson, 1992), 41.

Joseph Beuys

1921 - 1986

Beuys was born in Krefeld, Germany, raised in Kleve, and died in Düsseldorf. His early years coincided with the rise of Nazism; he was a member of the Hitler Youth and fought for Germany in World War II. As a young student Beuys had shown artistic promise in drawing, studied the piano and cello, and developed a strong interest in the natural sciences. One anecdote recounts that, in 1933, the teenage artist rescued a copy of Carl Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae when members of the Nazi Party had a book burning in the courtyard of his high school in Kleve. Whether or not this event actually took place, it establishes Beuys’s sense of himself as romantic, intellectual, and shamanistic, one with intense sensory recall, and one who rejected censorship and authoritarian regimes.

By the time he completed high school in spring 1941, Beuys had resolved to become a sculptor; however, he decided to join the Luftwaffe rather than being drafted. While training as an aircraft radio operator, he studied biology and zoology at the University of Poznan in Poland, which was then under German control. In 1942, Beuys was stationed in the Crimea as part of a dive-bomber unit, deploying as a rear gunner. In March 1944, he was gunned down and crashed. He was rescued, he later said, by “Tartars,” the nomadic Tatar tribesmen in the area. “I must have shot through the windscreen as it flew back at the same speed as the plane hit the ground and that saved me, though I had bad skull and jaw injuries. Then the tail flipped over and I was completely buried in the snow. That’s how the Tartars found me days later. I remember voices saying ‘Voda’ (water), then the felt of their tents, and the dense pungent smell of cheese, fat, and milk. They covered my body in fat to help it regenerate warmth, and wrapped it in felt as an insulator to keep warmth in.” [2] After recovering from his wounds he was sent back to the front in August. When Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, Beuys was sent to an internment camp in England, but by August he had returned to his parents’ home in Germany.

Following the war, Beuys resumed his art career; he studied at the Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts) between 1947 and 1953, studying with Ewald Mataré. He founded an artist society, the Donnerstag Gesellschaft (Thursday Group), with Hann Trier and other young artists in 1947 and they held exhibitions and programs through 1950. The 1950s were extremely difficult for Beuys, as he struggled with depression that, in retrospect, might have been post-traumatic stress disorder. Late in the decade he began to illustrate James Joyce’s Ulysses and this work, when completed in 1961, brought him critical attention. That same year he was given the position of Professor of Monumental Sculpture at his alma mater, the Kunstakademie, in Düsseldorf. Beuys was fired in 1972 because, among other things, he allowed anyone to attend his classes and had no requirements.

It was in Düsseldorf in 1962 that Beuys met the artist Nam June Paik, a member of the Fluxus movement comprised of avant-garde artists, musicians, and performance artists of different nationalities. As defined by its avowed leader, George Macunias, Fluxus productions “must appear to be complex, pretentious, profound, serious, intellectual, inspired, skillful, significant and theoretical.” [3] Through Paik, Beuys met the American musician and composer John Cage, for whom he had great admiration. Beuys was briefly associated with Fluxus but ultimately rejected their Dadaesque activities. He was more interested in negotiating societal change, blending his interests in science and spirituality, human creativity, and nature. He turned to installation and performance art to explore these interests.

Beuys represented Germany in the Venice Biennales of 1976 and 1980 and, in 1979, was given a one-man retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. A staunch pacifist and environmentalist, Beuys co-founded Germany’s Student Party in 1967, founded the Free International University in 1974, and was a co-founder of the Green Party in 1980. Beuys styled himself as an artist/shaman/educator/politician, and his cultural output encompassed performance pieces such as the seminal 1965 “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare,” the 1982 pop music video, “Sonne statt Reagan” (Sun, not Rain/Reagan), and “7000 Oaks: City Forestation Instead of City Administration” (1982–1987). For the first, Beuys smeared honey and gold leaf on his head and walked around his installation, murmuring indecipherably for three hours to the body of a dead hare he was holding. One of his last projects, “Oaks,” consisted of 7,000 four-foot tall black basalt markers paired with an equal number of oak trees planted throughout the city of Kassel, with the mission of encouraging individuals to effect eco-urbanization and environmental and social change on a global scale. Beuys died in Düsseldorf in January 1986, only a few years before the dismantling of the Berlin Wall, which the artist surely would have regarded as a quintessential Social Sculpture.

Notes:

[1] Beuys, “Artist’s statement,” in Zeitgest (New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1983), 82.

[2] Caroline Tisdall, Joseph Beuys (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1979), 16–17.

[3] Macunias quoted in Emmett Williams, My Life in Flux—and Vice Versa (London: Thames and Hudson, 1992), 41.

Person TypeIndividual