Josef Albers

An accomplished artist in a variety of media—painting, printmaking, glass, and furniture—Josef Albers (1888–1976) was also a renowned teacher at such distinguished institutions as the Bauhaus, Black Mountain College, and Yale University. He was the first living artist to be honored with a retrospective exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His life work was the study of visual perception and color, especially how colors relate and interact as their position, saturation, and value change.

Albers was born in Bottrop, in the highly industrialized Ruhr district of Germany, the son of a house painter and decorator. As a teenager, he began his studies to be a teacher, and in 1908 received his teaching certificate. For the next five years he was an instructor in public schools in Bottrop and other nearby towns. From 1913 to 1915, recognizing his growing interest in art, he studied at the Royal Art School in Berlin, and in 1918–1919, he attended the Bavarian Art Academy in Munich. During this time he worked in stained glass and made prints similar to the work of the German Expressionists.

In 1920, Albers moved to Weimar, to study at the one-year-old Bauhaus, a school dedicated to unifying craft and art with industrial design. He took the preliminary course with Johannes Itten, a color theorist, and entered the glass workshop. Three years later, Walter Gropius, the director of the school, asked Albers to replace Itten. In 1925, Albers married a well-to-do student from Berlin, Anneliese Fleischmann. Still working with glass, and also furniture design, he was appointed a Bauhaus Master while Anni flourished in the weaving workshop. Together they moved to Dessau, and remained with the school under the leadership of Mies van der Rohe until the National Socialist Party closed the avant-garde institution in 1933. Josef Albers was affiliated with the Bauhaus longer than anyone else.

At the age of forty-five, Albers had no job and few prospects given the rise of the Nazis. When invited to teach at a new school near Asheville, North Carolina, Josef and Anni gladly accepted, despite their ignorance about its location, and his lack of English language skills. They were the first of many Bauhaus people to come to America. Black Mountain College was an experimental school, with the arts at its core. While it never gained accreditation, and only fifty-five students graduated during its twenty-four year existence, it nevertheless shaped the destiny of many American artists. Among its distinguished faculty and students were such avant-garde thinkers as John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Buckminster Fuller, Jacob Lawrence, and Robert Motherwell. The educational philosophy was holistic and methods emphasized demonstration and practice. A student of Albers, noted artist Robert Rauschenberg, described his teacher: “Albers was a beautiful teacher and an impossible person. … He wasn’t easy to talk to, and I found his criticism so excruciating and so devastating that I never asked for it. Years later, though, I’m still learning what he taught me, because what he taught me had to do with the entire visual world. … I consider Albers the most important teacher I’ve ever had, and I’m sure he considered me one of his poorest students.” [1]

Since there were no glass facilities at Black Mountain College, Albers turned to painting and began his explorations in visual perception, not only of color, but also two-dimensional designs that appear three-dimensional. In 1935, he and Anni made their first of many trips to Mexico. He wrote his former Bauhaus colleague Wassily Kandinsky: “Mexico is truly the promised land of abstract art.” [2] In the late 1940s, the college continued to suffer financially, and was beset by disagreements among faculty members. As a result, Albers resigned his position at the end of the decade. He held visiting-artist positions at the University of Mexico, Cincinnati Art Academy, and the Pratt Institute, New York, before accepting the chairmanship of the Department of Design at Yale University in 1950.

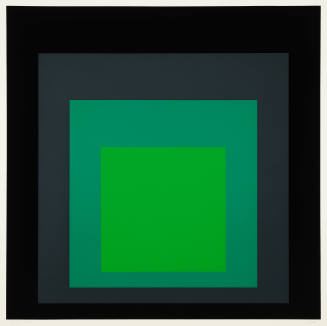

The previous year, Albers had begun his Homage to the Square series which ultimately would number one thousand variations in paintings and prints. Using four different formats of concentric squares, he systematically explored the behavior of color, first in oil, then lithography and screenprints. He explained his devotion to the subject: “I am interested particularly in the psychic effect—esthetic experience caused by the interaction of colors.” In 1963, using many of his students’ exercises as illustrations, Albers published the two-volume The Interaction of Color. A mammoth and complicated undertaking, the collaboration with Yale University Press required the services of three separate printers. Albers states in the introduction how he will emphasize practice over theory. Designed as a resource for teaching, the book is “a record of an experimental way of studying color and of teaching color. In visual perception a color is almost never seen as it really is—as it is physically. This fact makes color the most relative medium in art.” [3] He begins his text with a discussion of the color red, and how fifty different people have fifty different ideas about the color red.

Mandatory retirement from Yale University at the age of seventy in 1958 allowed Albers to disengage himself from the chores of academia, teach an occasional seminar, give lectures, and dedicate himself to his own art. In 1962, he was invited to be a visiting artist at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles, an experience that opened new avenues for his Homage to the Square series. Returning the next two years, he learned the technicalities of the medium, and simultaneously began to work with screenprints. He delighted in the greater variety and availability of printers’ inks, and in the idea that his work would become accessible to a broader audience.

Albers’s version of abstract art was personally detached and emphasized color, geometry, and clean lines; it was the antithesis to the major trend of the day, Abstract Expressionism. His influence on the next generation of artists—the minimalists and op artists—is inestimable, and his work on color perception has become the backbone of art education everywhere. Wishing to assure his legacy, in 1971 Albers established The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to further “the revelation and evocation of vision through art.” [4]

Notes:

[1] Interview with Jonathan Stix, May 8, 1972, Black Mountain College project papers, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, quoted in Mary Emma Harris, The Arts at Black Mountain College (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1987), 122.

[2] Albers to Kandinsky, August 22, 1936, quoted in Kandinsky-Albers: Une Correspondance des années trente (Paris: Musée d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1998), 79, quoted in Brenda Danilowitz, Josef Albers: A Catalogue Raisonné, 1915–1976 (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, 2001), 17.

[3] Albers quoted in George Heard Hamilton, Josef Albers—Paintings, Prints, Projects Exhibition catalogue. (New Haven, CT: Yale Art School, 1956), 36, quoted in Nicholas Fox Weber, et al. Josef Albers: A Retrospective (New York: Solomon Guggenheim Museum, 1988), 12, and Josef Albers, Interaction of Color (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, revised paperback edition, 1975), ix.

[4] The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, http://www.albersfoundation.org/Foundation.