Skip to main contentBiographyPainting at the end of the nineteenth century, the artist Thomas Hovenden (1840–1895) created well-composed scenes with strongly sentimental narratives. Compared to the work of more progressive contemporaries such as James McNeill Whistler, who was experimenting with form and color, and Mary Cassatt, whose approach to subject matter and perspective was influenced by the French Impressionists, Hovenden’s genre scenes seem old-fashioned. Even Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer, who also created figurative scenes and to whom Hovenden was often compared, may be seen as modernists in that they eschewed the type of sentimentality and moralizing that Hovenden embraced. Still, his work was popular and well received during his lifetime, and his drafting and compositional skills distinguish his paintings even today.

Born in Dunmanway, County Cork, Ireland, Hovenden was orphaned at an early age. He was apprenticed as a youth to a gilder and frame-maker who recognized his potential and supported his first artistic training at the Cork School of Design. [1] In 1863, Hovenden immigrated to America, settling in New York and supporting himself as a frame-maker. He enrolled in classes at the National Academy of Design, refining his drafting skills and studying in the life class. He exhibited his work at the Academy and he also took up lithography. In 1868, he moved to Baltimore, where he opened a studio and showed paintings at the Maryland Academy of Art.

Hovenden’s first oil paintings are romantic figure studies of women walking in the woods, tending flowers in a garden, or gazing pensively into space while seated in a comfortable parlor. They are skillfully done but lacking in spirit and vitality. No doubt seeking new inspiration, Hovenden traveled to France in 1874, on the advice of the Baltimore art patron William T. Walters, whose collection later formed the core of the Walters Art Museum, and was supported financially by John McCoy. In Paris, Hovenden studied with the academic artists Jules Breton and Alexandre Cabanel, under whose direction he further refined his drawing and painting skills. The more important influence on his work, however, proved to be the region of Brittany and the colony of expatriate American artists that he found there. Settling in Brittany in 1875, Hovenden took as his subject the local peasants, their picturesque dress, and rustic cottages.

The history of the Breton peasants inspired Hovenden’s most significant paintings to date. Captivated by the romantic story of the local Vendées, who nearly a century earlier had resisted the republican forces of the French Revolution in the name of piety and loyalty to the king, Hovenden painted several imagined versions of their story. A Breton Interior in 1793, 1878, private collection, shows an older man inspecting his sword before he hands it off to his son, who is armed with a musket. The young man’s wife regards them stoically, her arm draped over their baby’s crib, while a girl and an old woman form bullets for the coming battle. In Hoc Signo Vinces (In This Sign Shalt Thou Conquer), 1880, Detroit Institute of Arts, shows a wife piously pinning the emblem of the Brotherhood of the Sacred Heart onto her husband’s chest before he departs for the conflict. Both paintings are enlivened by domestic details such as carved wooden furniture, crockery, tapestries, and devotional statues.

These paintings were the first of several by the artist in which he imagined romantic scenes of the past. The legends of King Arthur inspired his Death of Elaine, 1882, Westmoreland Museum of American Art, a large-scale, multiple-figure rendering of the death of Elaine, who perished because of her unrequited love for Sir Lancelot. In the painting, Hovenden’s most ambitious thus far, Elaine lies on a bed, her fair hair and pale face drawing the viewer’s eye, while the richly dressed mourners surround her. Hovenden made several preparatory drawings and oil sketches for the painting, an indication of the importance he placed on the composition.

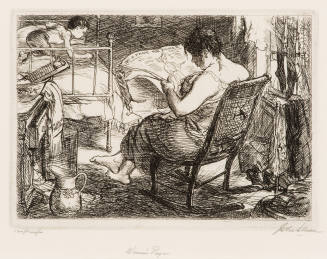

After Hovenden returned to the United States in 1880, he married Helen Corson, a fellow artist whom he had met in France, and settled in her hometown of Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania. The romantic and noble subjects that had occupied him in France must have seemed very remote, because almost immediately he began painting quiet genre scenes of one or two figures in humble domestic interiors. The connection between these two periods in his work, however, is not as tenuous as it might first appear. Paintings such as The Old Version (Sunday Afternoon), 1881, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and The Puzzled Voter, 1880, private collection, share with his Breton peasant paintings the lively attention to homey details and with his paintings of the Vendées and King Arthur’s court an intense interest in narrative.

Hovenden’s new home in Plymouth Meeting likely inspired the subjects that occupied him over the next several years: the lives of the African Americans who lived in the town, which had served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. The 1880s were a particularly difficult time for African Americans in the United States, as art historian Anne Terhune points out: “Within two months of Hovenden’s return to the United States, the presidential election of 1880 marked a turning point—both political party platforms abandoned the cause of Southern blacks, and Southern home rule triumphed. In 1883, the Supreme Court voided the 1875 Civil Rights Act that provided equal access to public places and public transportation. By the later 1880s and in the 1890s, many people in both the North and the South began to believe … that emancipation was a failure.” [2] Terhune summarizes the attitudes of many white writers at the time, who believed that the childlike nature of African Americans made them unfit for productive lives without the paternalistic influence of white slave-owners.

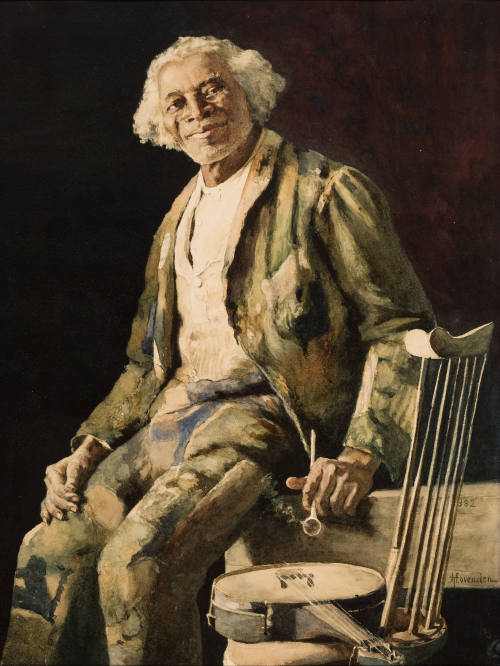

In this troubled context, Hovenden created some of his best-known paintings. Many, including Dat Possum Smell Pow’ful Good, 1881, Robert Hull Fleming Museum, University of Vermont, Sunday Morning, 1881, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and Chloe and Sam, 1882, Amon Carter Museum, feature a local laborer named Samuel Jones as a model. While departing radically from blatantly racist images of African Americans created by some of the artist’s contemporaries, such as cartoonist Thomas Nast, Hovenden’s paintings of African Americans are still jarring to modern viewers. Hovenden’s images of Jones reveal his subject’s humanity and humor, but the artist’s patronizing use of what he perceived as a black vernacular for the titles emphasizes Jones’s lack of education. Further, the frequent inclusion of musical instruments places Jones in a subservient “performer” role, while his smiling countenance belies the difficulties African Americans faced in the 1880s. In paintings such as Their Pride, 1888, the Union League Club of New York, in which a middle-aged couple regard their daughter as she models a new hat, Hovenden more successfully conveys the dignity of post-emancipation African American life. His painting The Last Moments of John Brown, 1884, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, depicts a tender and poignant moment as the fiery abolitionist stops to kiss a black baby on the way to his execution. Painting in the Quaker enclave of Plymouth Meeting, in a building which had once been used as a meeting place for abolitionists, Hovenden created images of blacks that revealed a great deal of his own, perhaps unconscious, ambivalence about their status in the late nineteenth century.

The most successful painting of Hovenden’s career, Breaking Home Ties, 1890, Philadelphia Museum of Art, does not feature African Americans. The painting depicts a young man taking leave of his family, presumably departing for more opportunity in the city. In the center of the composition, a middle-aged mother places her hands on her son’s shoulders and gazes sadly into his face. He does not meet her eye, staring resolutely forward and perhaps willing himself not to cry. They are surrounded by other family members—sisters, a grandmother, the family dog—and by the comforting homey details that mark Hovenden’s domestic interiors. At right, a man, probably the boy’s father, carries a valise out the door, perhaps to a waiting coach. The painting was a sensation at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, drawing thousands of visitors who responded emotionally to the painting’s recognizable story of familial love and loss.

In later years, Hovenden taught at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts after Thomas Eakins’s dismissal; Robert Henri and Alexander Calder numbered among his students. [3] In 1895, Hovenden died tragically at the age of fifty-five when he was struck by a train; Terhune, an authority on the artist, discounts stories that he died heroically trying to save a little girl who was crossing the railroad tracks; both the artist and the little girl perished in the accident. [4] Having reached the pinnacle of his career with the strong public reaction to Breaking Home Ties in 1893, Hovenden died before he could witness the diminished attention garnered by his sentimental style of genre painting. It was replaced by a new cosmopolitan aesthetic championed by American artists who looked to Europe, particularly to French Impressionism, for inspiration.

Notes:

[1] Anne Gregory Terhune, Thomas Hovenden: His Life and Art (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 2.

[2] Terhune, Thomas Hovenden: His Life and Art, 96.

[3] Anne Gregory Terhune, Sylvia Yount, Naurice Frank Woods, Jr., Thomas Hovenden (1840–1895): American Painter of Hearth and Homeland (Philadelphia, PA: The Woodmere Art Museum, 1995), 83.

[4] Terhune, Thomas Hovenden: His Life and Art, 185.

Thomas Hovenden

1840 - 1895

Born in Dunmanway, County Cork, Ireland, Hovenden was orphaned at an early age. He was apprenticed as a youth to a gilder and frame-maker who recognized his potential and supported his first artistic training at the Cork School of Design. [1] In 1863, Hovenden immigrated to America, settling in New York and supporting himself as a frame-maker. He enrolled in classes at the National Academy of Design, refining his drafting skills and studying in the life class. He exhibited his work at the Academy and he also took up lithography. In 1868, he moved to Baltimore, where he opened a studio and showed paintings at the Maryland Academy of Art.

Hovenden’s first oil paintings are romantic figure studies of women walking in the woods, tending flowers in a garden, or gazing pensively into space while seated in a comfortable parlor. They are skillfully done but lacking in spirit and vitality. No doubt seeking new inspiration, Hovenden traveled to France in 1874, on the advice of the Baltimore art patron William T. Walters, whose collection later formed the core of the Walters Art Museum, and was supported financially by John McCoy. In Paris, Hovenden studied with the academic artists Jules Breton and Alexandre Cabanel, under whose direction he further refined his drawing and painting skills. The more important influence on his work, however, proved to be the region of Brittany and the colony of expatriate American artists that he found there. Settling in Brittany in 1875, Hovenden took as his subject the local peasants, their picturesque dress, and rustic cottages.

The history of the Breton peasants inspired Hovenden’s most significant paintings to date. Captivated by the romantic story of the local Vendées, who nearly a century earlier had resisted the republican forces of the French Revolution in the name of piety and loyalty to the king, Hovenden painted several imagined versions of their story. A Breton Interior in 1793, 1878, private collection, shows an older man inspecting his sword before he hands it off to his son, who is armed with a musket. The young man’s wife regards them stoically, her arm draped over their baby’s crib, while a girl and an old woman form bullets for the coming battle. In Hoc Signo Vinces (In This Sign Shalt Thou Conquer), 1880, Detroit Institute of Arts, shows a wife piously pinning the emblem of the Brotherhood of the Sacred Heart onto her husband’s chest before he departs for the conflict. Both paintings are enlivened by domestic details such as carved wooden furniture, crockery, tapestries, and devotional statues.

These paintings were the first of several by the artist in which he imagined romantic scenes of the past. The legends of King Arthur inspired his Death of Elaine, 1882, Westmoreland Museum of American Art, a large-scale, multiple-figure rendering of the death of Elaine, who perished because of her unrequited love for Sir Lancelot. In the painting, Hovenden’s most ambitious thus far, Elaine lies on a bed, her fair hair and pale face drawing the viewer’s eye, while the richly dressed mourners surround her. Hovenden made several preparatory drawings and oil sketches for the painting, an indication of the importance he placed on the composition.

After Hovenden returned to the United States in 1880, he married Helen Corson, a fellow artist whom he had met in France, and settled in her hometown of Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania. The romantic and noble subjects that had occupied him in France must have seemed very remote, because almost immediately he began painting quiet genre scenes of one or two figures in humble domestic interiors. The connection between these two periods in his work, however, is not as tenuous as it might first appear. Paintings such as The Old Version (Sunday Afternoon), 1881, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and The Puzzled Voter, 1880, private collection, share with his Breton peasant paintings the lively attention to homey details and with his paintings of the Vendées and King Arthur’s court an intense interest in narrative.

Hovenden’s new home in Plymouth Meeting likely inspired the subjects that occupied him over the next several years: the lives of the African Americans who lived in the town, which had served as a stop on the Underground Railroad. The 1880s were a particularly difficult time for African Americans in the United States, as art historian Anne Terhune points out: “Within two months of Hovenden’s return to the United States, the presidential election of 1880 marked a turning point—both political party platforms abandoned the cause of Southern blacks, and Southern home rule triumphed. In 1883, the Supreme Court voided the 1875 Civil Rights Act that provided equal access to public places and public transportation. By the later 1880s and in the 1890s, many people in both the North and the South began to believe … that emancipation was a failure.” [2] Terhune summarizes the attitudes of many white writers at the time, who believed that the childlike nature of African Americans made them unfit for productive lives without the paternalistic influence of white slave-owners.

In this troubled context, Hovenden created some of his best-known paintings. Many, including Dat Possum Smell Pow’ful Good, 1881, Robert Hull Fleming Museum, University of Vermont, Sunday Morning, 1881, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and Chloe and Sam, 1882, Amon Carter Museum, feature a local laborer named Samuel Jones as a model. While departing radically from blatantly racist images of African Americans created by some of the artist’s contemporaries, such as cartoonist Thomas Nast, Hovenden’s paintings of African Americans are still jarring to modern viewers. Hovenden’s images of Jones reveal his subject’s humanity and humor, but the artist’s patronizing use of what he perceived as a black vernacular for the titles emphasizes Jones’s lack of education. Further, the frequent inclusion of musical instruments places Jones in a subservient “performer” role, while his smiling countenance belies the difficulties African Americans faced in the 1880s. In paintings such as Their Pride, 1888, the Union League Club of New York, in which a middle-aged couple regard their daughter as she models a new hat, Hovenden more successfully conveys the dignity of post-emancipation African American life. His painting The Last Moments of John Brown, 1884, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, depicts a tender and poignant moment as the fiery abolitionist stops to kiss a black baby on the way to his execution. Painting in the Quaker enclave of Plymouth Meeting, in a building which had once been used as a meeting place for abolitionists, Hovenden created images of blacks that revealed a great deal of his own, perhaps unconscious, ambivalence about their status in the late nineteenth century.

The most successful painting of Hovenden’s career, Breaking Home Ties, 1890, Philadelphia Museum of Art, does not feature African Americans. The painting depicts a young man taking leave of his family, presumably departing for more opportunity in the city. In the center of the composition, a middle-aged mother places her hands on her son’s shoulders and gazes sadly into his face. He does not meet her eye, staring resolutely forward and perhaps willing himself not to cry. They are surrounded by other family members—sisters, a grandmother, the family dog—and by the comforting homey details that mark Hovenden’s domestic interiors. At right, a man, probably the boy’s father, carries a valise out the door, perhaps to a waiting coach. The painting was a sensation at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, drawing thousands of visitors who responded emotionally to the painting’s recognizable story of familial love and loss.

In later years, Hovenden taught at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts after Thomas Eakins’s dismissal; Robert Henri and Alexander Calder numbered among his students. [3] In 1895, Hovenden died tragically at the age of fifty-five when he was struck by a train; Terhune, an authority on the artist, discounts stories that he died heroically trying to save a little girl who was crossing the railroad tracks; both the artist and the little girl perished in the accident. [4] Having reached the pinnacle of his career with the strong public reaction to Breaking Home Ties in 1893, Hovenden died before he could witness the diminished attention garnered by his sentimental style of genre painting. It was replaced by a new cosmopolitan aesthetic championed by American artists who looked to Europe, particularly to French Impressionism, for inspiration.

Notes:

[1] Anne Gregory Terhune, Thomas Hovenden: His Life and Art (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 2.

[2] Terhune, Thomas Hovenden: His Life and Art, 96.

[3] Anne Gregory Terhune, Sylvia Yount, Naurice Frank Woods, Jr., Thomas Hovenden (1840–1895): American Painter of Hearth and Homeland (Philadelphia, PA: The Woodmere Art Museum, 1995), 83.

[4] Terhune, Thomas Hovenden: His Life and Art, 185.

Person TypeIndividual