John Sloan

John Sloan (1871–1951) is perhaps best remembered today as one of the most significant and prolific members of the Ashcan School, the group of artists who embraced the vitality of early twentieth-century urban life and depicted it in vivid, gritty glory. Rejected by the National Academy of Design for their bold, painterly styles and contemporary, unsentimental subjects, the group, which included William Glackens, Robert Henri, George Luks, and Everett Shinn, mounted a groundbreaking exhibition in 1908 at Macbeth Galleries. The exhibition launched Sloan as a painter, but it was in the medium of etching that Sloan began his artistic career and by which he supported himself for many years while he struggled to find success.

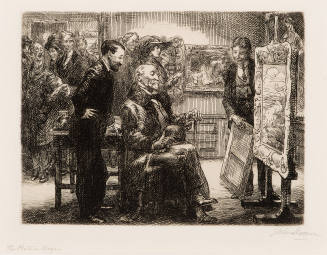

Sloan was born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, but moved to Philadelphia with his family when he was a boy. [1] He attended two years of high school, where his classmates included Glackens and future art collector Albert C. Barnes, but his family’s financial difficulties forced him to withdraw from school at the age of sixteen to earn money. One of his first jobs was in a bookstore that had a collection of prints, and the proprietor encouraged him to try his hand at etching. His first efforts, copies after Rembrandt, proved successful enough that Sloan acquired his own plate and needle. After a failed attempt to set himself up as a freelance illustrator, Sloan took a position at the Philadelphia Inquirer, later moving to the Philadelphia Press. He also studied some at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, but disagreements with his instructor, Thomas Anshutz, led him to withdraw.

In 1892, Sloan met Robert Henri, who would prove to be a significant influence on his life. Henri, already an accomplished artist, had just returned from three years in Europe, where he had found inspiration in such Old Masters as Frans Hals and Diego Velazquez. Henri advocated for the “subordination of so-called ‘finish’ to broad effects, simplicity of planes, purity and strength of color, and particularly the preservation of that impression which first delighted the sense of beauty and caused the subject to be chosen.” [2] Sloan, who had been frustrated by the stilted academic instruction at the Academy, embraced Henri’s bold, avant-garde approach.

In the late 1890s, many of Sloan’s friends in Philadelphia decamped for New York, attracted by more plentiful newspaper, book illustration, and exhibition opportunities. Sloan was hesitant to follow, in part because he had begun an affair with a troubled and fragile woman named Anna “Dolly” Wall, and he was fearful that a move would upset her. In 1904, however, the couple married and moved to New York, settling in Chelsea. The neighborhood had a shabby bohemian quality that appealed to them. Sloan undertook illustration work for such popular magazines as Century, Collier’s, Saturday Evening Post, McClure’s, and Scribner’s.

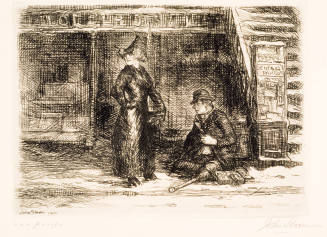

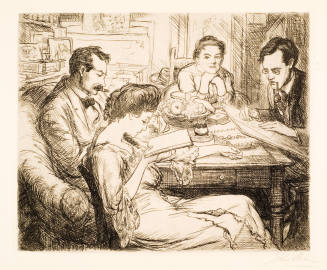

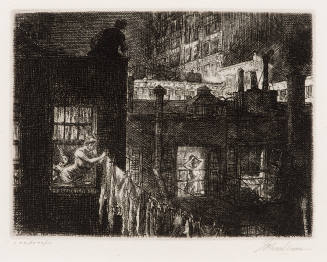

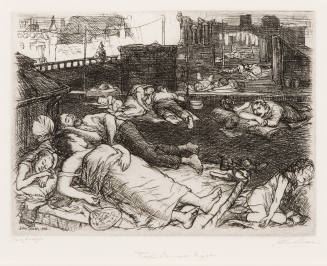

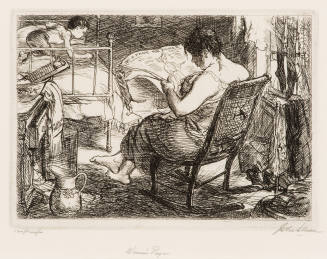

At this time, Sloan was also involved in a project to illustrate a deluxe edition of fifty novels by the French author Paul de Kock. The project was not only a good source of income; it proved beneficial in another way as well, as it inspired Sloan to embrace etching more fully. In 1905, he began the New York City Life series, which documented the scenes that he had observed in his new neighborhood: amusing and poignant, public and private. He completed ten etchings between 1905 and 1906 and added three more in 1910–1911.

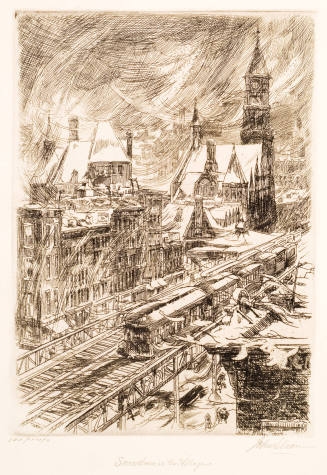

His experiments with this different subject matter breathed renewed life into his painting as well. Examples of his work from Philadelphia, Walnut Street Theater, Independence Square, and Philadelphia Stock Exchange, had focused more on buildings and their architectural features rather than people. Now, with the success—artistic, if not commercial—of the New York City Life series, Sloan began to feature people more prominently. The period from 1907 to 1912 was especially prolific, during which Sloan produced some of his most innovative and memorable images. Like his earlier Philadelphia work, these paintings often depicted urban scenes, for instance, Hairdresser’s Window, 1907; Election Night, 1907; Movies, Five Cents, 1907; and Picture Shop Window, 1907–1908. Later paintings such as South Beach Bathers, 1907–1908; Chinese Restaurant, 1909; Three A.M., 1909; Red Kimono on the Roof, 1912; and The Carmine Street Theater, 1912 featured the lives and interactions of people both outdoors and in. All of these paintings demonstrate Sloan’s signature style: active and vigorous brushwork and a penchant for dark tones enlivened by periodic strokes of brilliant color.

For the exhibition at Macbeth Galleries in 1908, Sloan chose only works from the preceding year; in addition to the 1907 works mentioned above, he included Easter Eve, Sixth Avenue and Thirtieth Street, The Cot, Nursemaids, and Madison Square. Many critics attacked what they perceived as the vulgarity of Sloan’s subject matter and painting style, but others praised the freshness of his vision and the vitality of his subjects. [3] The artists who participated in the exhibition at Macbeth Galleries, dubbed the Eight, achieved a marked degree of notoriety, but, with the arrival of modern art in the form of the 1913 Armory Show, they were no longer the cause célèbre.

Sloan’s interests over the next several decades were varied. Politically radical, he joined the Socialist party and served on the editorial board of the Socialist periodical The Masses. In addition, he and his wife Dolly campaigned for women’s suffrage. Artistically, he experimented with a new color system designed by artist Hardesty Maratta, introduced to him by Henri. Sloan also rendered the nude as a frequent subject, attempting to improve his understanding of anatomy, which was never strong due to his limited formal training. His treatment of the city changed as well, as he painted more and more from a bird’s-eye perspective, showing the city’s skyline from a high elevation. He taught at the Art Students League and wrote a book of instruction entitled The Gist of Art: Principles and Practice Expounded in the Classroom and Studio, 1939. He and Dolly traveled, spending summers in Gloucester, Massachusetts, or in New Mexico. After Dolly’s death, Sloan married a former student, Helen Farr, who, after he passed away in 1951, became his champion, preserving and advancing his reputation as a keen chronicler of modern city life. Intellectual, unconventional, bohemian and radical, moody, funny, and sociable, Sloan is revered today for his dynamic and amusing investigations of social relationships and the urban environment.

Notes:

[1] See John Loughery, John Sloan: Painter and Rebel (New York: H. Holt, 1995).

[2] Robert Henri, quoted in Loughery, John Sloan, 26.

[3] Heather Campbell Coyle and Joyce K. Schiller, John Sloan’s New York (Wilmington, DE: Delaware Art Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2007), 49.