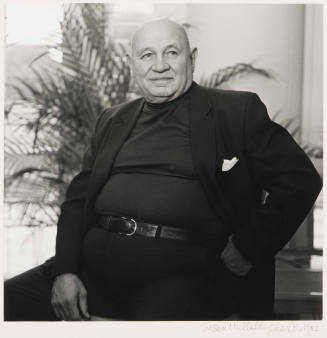

Skip to main contentBiographyRobert Gwathmey (1903–1988) was an artist associated with Social Realism, a movement within American Scene painting that first emerged during the 1930s. Social Realism was distinct from its contemporary, Regionalism, in that it was urban-based and progressive, while the latter was agrarian and reactionary. An eighth-generation Virginian, Gwathmey was born in Richmond eight months after his father, an engineer, was tragically killed while working on a locomotive. Following high school, Gwathmey studied briefly at North Carolina State University and then spent a year at the Maryland Institute School of Art and Design in Baltimore. During the summer of 1925, he worked his way to Europe on a freighter. Between 1926 and 1930, he studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and was awarded two Cresson scholarships for summer travel in Europe.

By the 1930s, Gwathmey was an active member in the leftist Artists’ Union, which promoted art and social change. Upon his return to the South after his first year in Philadelphia he saw with intense clarity the inherent racism of the region and the adverse situation of African Americans. In 1938, he moved to Pittsburgh for a teaching job at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. He achieved his first major artistic success in 1939 when he won a national competition from the federal government to paint a mural for the post office in Eutaw, Alabama. He also received a Rosenwald Foundation grant, which he used during the summer of 1944 to live with a sharecropper’s family in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. For many years Gwathmey returned to Norfolk, Virginia, during the summers to draw and study laborers there.

Gwathmey’s wife Rosalie had studied photography at the Photo League in New York and, in the 1940s, her photographs were an important resource for her husband’s paintings. She gave up photography in 1951, however, and by 1955 had disposed of her equipment, destroyed her negatives, and given away her prints—all because of unbearable pressure from the Federal Bureau of Investigation; a mole had reported that the Photo League was leftist and un-American. Well into the 1970s, Gwathmey himself remained under observation by the FBI for his socialist sympathies.

An admirer of the nineteenth-century French artist Honoré Daumier, Gwathmey chose from the start of his career to depict African-American sharecroppers and to focus on themes of social injustice. In addition, he was influenced by Pablo Picasso, and aspects of Gwathmey’s style, especially the flattened planes and segmented forms, suggest the impact of Synthetic Cubism. Gwathmey was also aware of the French artist Georges Rouault, whose paintings resemble Gothic stained glass windows in their use of heavy outlines surrounding areas of intense color. However, unlike Rouault, Gwathmey was not deeply religious.

Gwathmey did not mind being called the “white Jacob Lawrence,” as he was a friend of the artist; they were both represented initially by the ACA Gallery and then Terry Dintenfass Inc., both in New York City. Gwathmey was friendly with fellow Social Realists Jack Levine, Ben Shahn, and, especially, Philip Evergood. From 1942 until 1968, Gwathmey taught evening and Saturday classes at the Cooper Union School of Art in New York. He was a National Academician at the National Academy of Design and a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters. By the late 1960s, Gwathmey was no longer making trips to North Carolina and Virginia, and when he moved to Amagansett, Long Island, his work became less politically charged, although still symbolic, and with a heightened interest in still life and nature. Gwathmey died in 1988, in the home and studio that his son Charles, a distinguished modernist architect, had designed twenty years earlier.

In 1951, Gwathmey filled out a questionnaire from the Whitney Museum of American Art, and, when asked to describe his philosophy of art wrote, “I think of the artist as the rounded man, working free of compromise and constantly seeking the meaning of his work and his society. … Cultural movements have been forces of good, or order, of aspirations and they have on occasion been throttled and distorted by reactionary movements. Art in its affirmation, its criticism, has helped point the way, and goes beyond merely reflecting society. … I like to tell a story and I want it to be understood. … No work of art can possibly exist without the exploration of the formal and aesthetic qualities. It is the fusion of this with the subject matter that gives an art totality.” [1]

Notes:

[1] Gwathmey, response to Whitney Museum of American Art questionnaire, March 27, 1951, copy, Reynolda House Museum of American Art files.

Robert Gwathmey

1903 - 1988

By the 1930s, Gwathmey was an active member in the leftist Artists’ Union, which promoted art and social change. Upon his return to the South after his first year in Philadelphia he saw with intense clarity the inherent racism of the region and the adverse situation of African Americans. In 1938, he moved to Pittsburgh for a teaching job at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. He achieved his first major artistic success in 1939 when he won a national competition from the federal government to paint a mural for the post office in Eutaw, Alabama. He also received a Rosenwald Foundation grant, which he used during the summer of 1944 to live with a sharecropper’s family in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. For many years Gwathmey returned to Norfolk, Virginia, during the summers to draw and study laborers there.

Gwathmey’s wife Rosalie had studied photography at the Photo League in New York and, in the 1940s, her photographs were an important resource for her husband’s paintings. She gave up photography in 1951, however, and by 1955 had disposed of her equipment, destroyed her negatives, and given away her prints—all because of unbearable pressure from the Federal Bureau of Investigation; a mole had reported that the Photo League was leftist and un-American. Well into the 1970s, Gwathmey himself remained under observation by the FBI for his socialist sympathies.

An admirer of the nineteenth-century French artist Honoré Daumier, Gwathmey chose from the start of his career to depict African-American sharecroppers and to focus on themes of social injustice. In addition, he was influenced by Pablo Picasso, and aspects of Gwathmey’s style, especially the flattened planes and segmented forms, suggest the impact of Synthetic Cubism. Gwathmey was also aware of the French artist Georges Rouault, whose paintings resemble Gothic stained glass windows in their use of heavy outlines surrounding areas of intense color. However, unlike Rouault, Gwathmey was not deeply religious.

Gwathmey did not mind being called the “white Jacob Lawrence,” as he was a friend of the artist; they were both represented initially by the ACA Gallery and then Terry Dintenfass Inc., both in New York City. Gwathmey was friendly with fellow Social Realists Jack Levine, Ben Shahn, and, especially, Philip Evergood. From 1942 until 1968, Gwathmey taught evening and Saturday classes at the Cooper Union School of Art in New York. He was a National Academician at the National Academy of Design and a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters. By the late 1960s, Gwathmey was no longer making trips to North Carolina and Virginia, and when he moved to Amagansett, Long Island, his work became less politically charged, although still symbolic, and with a heightened interest in still life and nature. Gwathmey died in 1988, in the home and studio that his son Charles, a distinguished modernist architect, had designed twenty years earlier.

In 1951, Gwathmey filled out a questionnaire from the Whitney Museum of American Art, and, when asked to describe his philosophy of art wrote, “I think of the artist as the rounded man, working free of compromise and constantly seeking the meaning of his work and his society. … Cultural movements have been forces of good, or order, of aspirations and they have on occasion been throttled and distorted by reactionary movements. Art in its affirmation, its criticism, has helped point the way, and goes beyond merely reflecting society. … I like to tell a story and I want it to be understood. … No work of art can possibly exist without the exploration of the formal and aesthetic qualities. It is the fusion of this with the subject matter that gives an art totality.” [1]

Notes:

[1] Gwathmey, response to Whitney Museum of American Art questionnaire, March 27, 1951, copy, Reynolda House Museum of American Art files.

Person TypeIndividual