Skip to main contentBiographyWith the rise of the women’s movement in the 1960s, many artists joined the effort to gain greater recognition and improve conditions for women in general. Joining the fray, May Stevens—a feminist artist, writer, teacher, editor, and social activist—believes art can be used as a tool for social change. In her art, Stevens “examines specific women’s lives in relation to the patriarchal structuring of class and privilege, and the polarities of abnormal/normal, silent/vocal, acceptance/resistance.” [1]

In 1924, May Stevens was born in Quincy, Massachusetts, to a working class family; her father, a pipefitter, was employed at the shipyard and her mother was a housewife. Stevens was the first in her family to graduate from college. She studied at the Massachusetts College of Art, receiving her bachelor of fine arts degree in 1948 and, five years later, her master of fine arts. She attended the Art Students League in New York, where she met Rudolf Baranik, whom she married in 1948. They moved to Paris on Baranik’s G. I. Bill, where they studied at the Académie Julian and began to exhibit their work. After three years abroad they returned to the United States. Stevens finished her graduate degree and, from 1953 to 1957, taught at the High School of Music and Art in New York City, then the Parsons School of Design from 1957 to 1961, and, beginning in 1963, at the School of Visual Art.

As a committed socialist, whose body of work embodies the feminist adage, “the personal is political,” Stevens gained considerable critical attention for her Big Daddy series. In it, she adapted an image of her father to critique the military and patriarchal power structure of the 1960s. She explained: “The portrait of my father, undershirted, before a blank TV screen turned eventually into a symbol of American complicity in the war in Southeast Asia. I named the figure Big Daddy. It became, through painting after painting, a monster (smiling, congenial) of my own making and finally had little to do with the man it was based on.” [2]

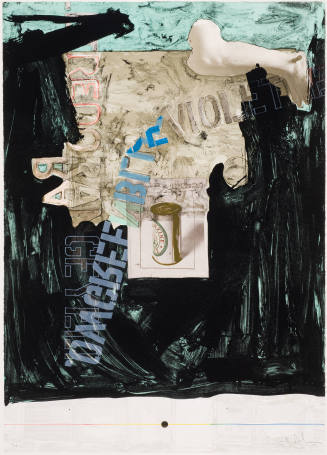

Stevens became increasingly involved in the women’s movement and continued her participation into the 1980s. She was active in forming the feminist collective Heresies in 1976, which published a scholarly journal, and she was influenced by feminist thought, such as the writings of Adrienne Rich and others. After the Big Daddy series, she explored representations of her mother. Stevens said of the specific images of her parents that prompted her work, “they were…terrible to see, revealing of what life had done to these people I loved, and of what they had done to each other. The photograph of my mother was too terrible for me to deal with. I started to paint my father.” [3] She began what may be her best-known series in 1976, entitled Ordinary/Extraordinary, which juxtaposed her mother with Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish-German revolutionary and political activist. According to one critic, Stevens “layered her own memories and feelings with the personal and public images of two women, one of whom lived her life entirely within the confines of family and work, the other of one who played a public historical role. Stevens exposed the false dichotomy between the public and the private in art and in history. Employing paintings, collages and the artist’s book, she revealed the human side of Luxemburg and made public the silent life of her own working-class mother, whose personal suffering represents the political oppression of all disadvantaged women for whom collective action is impossible without knowledge of history.” [4]

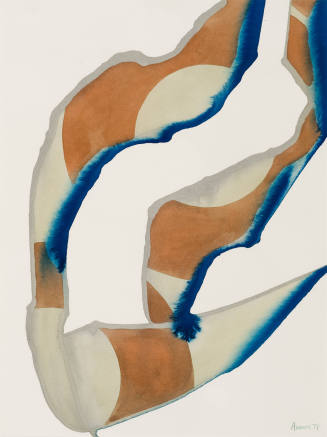

Later in her career, Stevens shifted her focus to landscape, particularly water, and the use of text passages as visual form.

Notes:

[1] Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art, and Society (London: Thames & Hudson, 1996), 361.

[2] May Stevens, “My Work and My Working-Class Father,” in Working It Out: 23 Women Writers, Artists, Scientists, and Scholars Talk about their Lives and Work, ed. Pamela Ruddick, Sara Ruddick, and Pamela Daniels (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977), 113.

[3] Stevens, “My Work,” 112.

[4] Chadwick, Women, Art, and Society, 361–362.

May Stevens

born 1924

In 1924, May Stevens was born in Quincy, Massachusetts, to a working class family; her father, a pipefitter, was employed at the shipyard and her mother was a housewife. Stevens was the first in her family to graduate from college. She studied at the Massachusetts College of Art, receiving her bachelor of fine arts degree in 1948 and, five years later, her master of fine arts. She attended the Art Students League in New York, where she met Rudolf Baranik, whom she married in 1948. They moved to Paris on Baranik’s G. I. Bill, where they studied at the Académie Julian and began to exhibit their work. After three years abroad they returned to the United States. Stevens finished her graduate degree and, from 1953 to 1957, taught at the High School of Music and Art in New York City, then the Parsons School of Design from 1957 to 1961, and, beginning in 1963, at the School of Visual Art.

As a committed socialist, whose body of work embodies the feminist adage, “the personal is political,” Stevens gained considerable critical attention for her Big Daddy series. In it, she adapted an image of her father to critique the military and patriarchal power structure of the 1960s. She explained: “The portrait of my father, undershirted, before a blank TV screen turned eventually into a symbol of American complicity in the war in Southeast Asia. I named the figure Big Daddy. It became, through painting after painting, a monster (smiling, congenial) of my own making and finally had little to do with the man it was based on.” [2]

Stevens became increasingly involved in the women’s movement and continued her participation into the 1980s. She was active in forming the feminist collective Heresies in 1976, which published a scholarly journal, and she was influenced by feminist thought, such as the writings of Adrienne Rich and others. After the Big Daddy series, she explored representations of her mother. Stevens said of the specific images of her parents that prompted her work, “they were…terrible to see, revealing of what life had done to these people I loved, and of what they had done to each other. The photograph of my mother was too terrible for me to deal with. I started to paint my father.” [3] She began what may be her best-known series in 1976, entitled Ordinary/Extraordinary, which juxtaposed her mother with Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish-German revolutionary and political activist. According to one critic, Stevens “layered her own memories and feelings with the personal and public images of two women, one of whom lived her life entirely within the confines of family and work, the other of one who played a public historical role. Stevens exposed the false dichotomy between the public and the private in art and in history. Employing paintings, collages and the artist’s book, she revealed the human side of Luxemburg and made public the silent life of her own working-class mother, whose personal suffering represents the political oppression of all disadvantaged women for whom collective action is impossible without knowledge of history.” [4]

Later in her career, Stevens shifted her focus to landscape, particularly water, and the use of text passages as visual form.

Notes:

[1] Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art, and Society (London: Thames & Hudson, 1996), 361.

[2] May Stevens, “My Work and My Working-Class Father,” in Working It Out: 23 Women Writers, Artists, Scientists, and Scholars Talk about their Lives and Work, ed. Pamela Ruddick, Sara Ruddick, and Pamela Daniels (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977), 113.

[3] Stevens, “My Work,” 112.

[4] Chadwick, Women, Art, and Society, 361–362.

Person TypeIndividual