Skip to main contentBiographySpouses of highly visible and notorious figures—whether in the arts or politics—face numerous challenges. When both husband and wife are accomplished in the same field, the potential for tension is even greater. Such was the case for Lee Krasner (1908–1984), who was married to the great and tumultuous Abstract Expressionist painter Jackson Pollock from 1945 until 1956. A skillful artist before their marriage and in her own right, Krasner also worked hard to promote Pollock’s career during his lifetime and afterward. Although she was the only woman member of the first generation of Abstract Expressionists, recognition came to her late, in part due to her gender and also because she was overshadowed by Pollock. She was adamant, however: “As an artist I never thought of myself as anything but LEE KRASNER. I’m always going to be Mrs. Pollock—that’s a matter of fact—but I’ve never used the name Pollock in connection with my work. I painted before Pollock, during Pollock, and after Pollock.” [1]

Krasner was raised in a traditional Orthodox Jewish household in Brooklyn, her birthplace. Declaring an interest in art, Krasner, after two attempts, gained acceptance to Washington Irving High School in Manhattan—the only public school where a girl could study art. From 1926 to 1928, she attended the Women’s Art School of The Cooper Union, followed by a short period at the Art Students League and two years at the National Academy of Design. A determined and often rebellious student, Krasner objected to certain policies, such as one that prevented women from going to the basement, the only place where fish could be studied for still lifes. Living in Greenwich Village with fellow artist Igor Pantuhoff, Krasner supported herself as an artist’s model and waitress and studied to be a teacher, although she never taught.

In early 1934, Krasner began to work for the Public Works of Art Project, and the following year she was assigned to the Mural Division of the Fine Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration. Like many artists during the Depression, she became involved in leftist politics; she saw Picasso’s Guernica at the Valentine Gallery as part of an exhibit to raise funds for Spanish refugees. For her, it was a powerful experience: “It knocked me right out of the room, I circled the block four or five times, and then went back and took another look at it. I’m sure I was not alone in that kind of reaction. … You’re overwhelmed in many directions when you’re congenially confronted with, let’s say, a painting like Guernica for the first time. It disturbs so many elements in one given second, you can’t say ‘I want to paint like that.’ It isn’t that simple.” [2]

In 1937, Krasner became a student of Hans Hofmann, a rigorous instructor who both challenged and encouraged her. She became acquainted with his “push-pull” theory of color—that some colors recede while others advance—and, under his guidance, she embarked on her first abstractions. Later, in the 1950s, she used many of the charcoal drawings of figures and still life from Hofmann’s classes in large-format collages. But most important for Krasner was his admiration of both Picasso and Matisse, an appreciation she would emulate in her work, balancing the cubist form of the former and the color of the latter.

Krasner’s circle of friends and colleagues was expansive, and included such critics as Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg and the painters Arshile Gorky and Willem deKooning. An admirer of Piet Mondrian, she shared with him a passion for jazz and dance, and recalled, “I was a fairly good dancer, that is to say, I can follow easily, but the complexity of Mondrian’s rhythm was not simple in any sense.” [3] She participated and exhibited with the American Abstract Artists, a leftist-leaning organization active in the 1940s, which advocated for the rights of artists. At a 1941 exhibition, she encountered Pollock, and their relationship soon evolved as they worked together on the War Services Project designing posters and displays. In 1945, they married and moved to Springs, a small, rural settlement on eastern Long Island, one hundred miles from Manhattan.

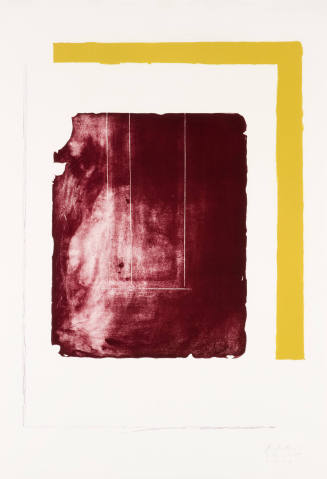

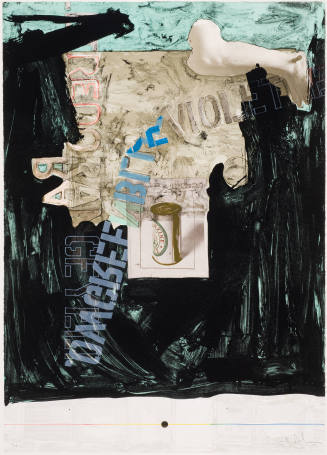

Despite some dry spells and time devoted to assisting Pollock with his career, Krasner continued her own painting, usually developing ideas in series. Her Little Images of the late 1940s are densely packed intimate works in which she clearly reveled in the viscosity of her medium. These were followed by more geometric compositions and a predilection for vertical canvases that have quasi-figurative elements. In the 1950s, she was captivated by collage, often using older, discarded work. She explained “I go back on myself, into my own work, destroy it in some way or reutilize it in some way and come up with a new thing. … I’m constantly going back to something I did earlier, doing something else with it and coming forth with another more clarified image.” [4]

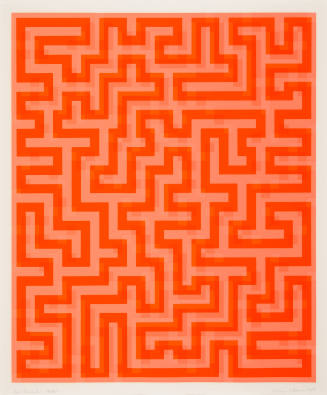

Reflecting her earlier work on murals as well as the large-scale paintings of her contemporaries, Krasner’s canvases were big, but never so large that she had to use a ladder. Her characteristic arcing organic shapes revert to previous drawings of the figure and reveal the broad gestures that she used to apply paint. She understood the sources and cycles of her work: “All my work keeps going like a pendulum; it seems to swing back to something I was involved in earlier, or it moves between horizontality and verticality, circularity, or a composite of them. For me, I suppose that change is the only constant.” [5]

Notes:

[1] Krasner quoted in David Bourdon, “Lee Krasner: I’m Embracing the Past,” Village Voice, March 7, 1977, 57, quoted in Robert Hobbs, Modern Masters: Lee Krasner (New York, Abbeville Press, 1993), 100.

[2] Krasner, interview with Barbara Rose, July 31, 1966, quoted in Gail Levin, Lee Krasner: A Biography (New York: Harper Collins, 2011), 135.

[3] Krasner quoted in Virginia Pitts Rembert, Mondrian in the USA (New York: Parkstone Press, Ltd, 2002), quoted in Levin, Lee Krasner, 181.

[4] Krasner, interview with Barbara Novak, Boston, October 1979, recorded for WBGH New TV workshop, quoted in Jeffrey D. Grove, Lee Krasner After Palingenesis (New York: Robert Miller Gallery, 2003), unpaginated.

[5] Krasner quoted in Marcia Tucker, Lee Krasner: Large Paintings (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1973), quoted in Barbara Rose, Lee Krasner: A Retrospective (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1983), 139.

Lee Krasner

1908 - 1984

Krasner was raised in a traditional Orthodox Jewish household in Brooklyn, her birthplace. Declaring an interest in art, Krasner, after two attempts, gained acceptance to Washington Irving High School in Manhattan—the only public school where a girl could study art. From 1926 to 1928, she attended the Women’s Art School of The Cooper Union, followed by a short period at the Art Students League and two years at the National Academy of Design. A determined and often rebellious student, Krasner objected to certain policies, such as one that prevented women from going to the basement, the only place where fish could be studied for still lifes. Living in Greenwich Village with fellow artist Igor Pantuhoff, Krasner supported herself as an artist’s model and waitress and studied to be a teacher, although she never taught.

In early 1934, Krasner began to work for the Public Works of Art Project, and the following year she was assigned to the Mural Division of the Fine Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration. Like many artists during the Depression, she became involved in leftist politics; she saw Picasso’s Guernica at the Valentine Gallery as part of an exhibit to raise funds for Spanish refugees. For her, it was a powerful experience: “It knocked me right out of the room, I circled the block four or five times, and then went back and took another look at it. I’m sure I was not alone in that kind of reaction. … You’re overwhelmed in many directions when you’re congenially confronted with, let’s say, a painting like Guernica for the first time. It disturbs so many elements in one given second, you can’t say ‘I want to paint like that.’ It isn’t that simple.” [2]

In 1937, Krasner became a student of Hans Hofmann, a rigorous instructor who both challenged and encouraged her. She became acquainted with his “push-pull” theory of color—that some colors recede while others advance—and, under his guidance, she embarked on her first abstractions. Later, in the 1950s, she used many of the charcoal drawings of figures and still life from Hofmann’s classes in large-format collages. But most important for Krasner was his admiration of both Picasso and Matisse, an appreciation she would emulate in her work, balancing the cubist form of the former and the color of the latter.

Krasner’s circle of friends and colleagues was expansive, and included such critics as Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg and the painters Arshile Gorky and Willem deKooning. An admirer of Piet Mondrian, she shared with him a passion for jazz and dance, and recalled, “I was a fairly good dancer, that is to say, I can follow easily, but the complexity of Mondrian’s rhythm was not simple in any sense.” [3] She participated and exhibited with the American Abstract Artists, a leftist-leaning organization active in the 1940s, which advocated for the rights of artists. At a 1941 exhibition, she encountered Pollock, and their relationship soon evolved as they worked together on the War Services Project designing posters and displays. In 1945, they married and moved to Springs, a small, rural settlement on eastern Long Island, one hundred miles from Manhattan.

Despite some dry spells and time devoted to assisting Pollock with his career, Krasner continued her own painting, usually developing ideas in series. Her Little Images of the late 1940s are densely packed intimate works in which she clearly reveled in the viscosity of her medium. These were followed by more geometric compositions and a predilection for vertical canvases that have quasi-figurative elements. In the 1950s, she was captivated by collage, often using older, discarded work. She explained “I go back on myself, into my own work, destroy it in some way or reutilize it in some way and come up with a new thing. … I’m constantly going back to something I did earlier, doing something else with it and coming forth with another more clarified image.” [4]

Reflecting her earlier work on murals as well as the large-scale paintings of her contemporaries, Krasner’s canvases were big, but never so large that she had to use a ladder. Her characteristic arcing organic shapes revert to previous drawings of the figure and reveal the broad gestures that she used to apply paint. She understood the sources and cycles of her work: “All my work keeps going like a pendulum; it seems to swing back to something I was involved in earlier, or it moves between horizontality and verticality, circularity, or a composite of them. For me, I suppose that change is the only constant.” [5]

Notes:

[1] Krasner quoted in David Bourdon, “Lee Krasner: I’m Embracing the Past,” Village Voice, March 7, 1977, 57, quoted in Robert Hobbs, Modern Masters: Lee Krasner (New York, Abbeville Press, 1993), 100.

[2] Krasner, interview with Barbara Rose, July 31, 1966, quoted in Gail Levin, Lee Krasner: A Biography (New York: Harper Collins, 2011), 135.

[3] Krasner quoted in Virginia Pitts Rembert, Mondrian in the USA (New York: Parkstone Press, Ltd, 2002), quoted in Levin, Lee Krasner, 181.

[4] Krasner, interview with Barbara Novak, Boston, October 1979, recorded for WBGH New TV workshop, quoted in Jeffrey D. Grove, Lee Krasner After Palingenesis (New York: Robert Miller Gallery, 2003), unpaginated.

[5] Krasner quoted in Marcia Tucker, Lee Krasner: Large Paintings (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1973), quoted in Barbara Rose, Lee Krasner: A Retrospective (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1983), 139.

Person TypeIndividual