Anni Albers

The Bauhaus, founded in 1919, revolutionized instruction in art, architecture, and design. Located first in Weimar, Germany, then Dessau, it sought to utilize modern materials and streamline the appearance of all manner of things, from buildings to coffee cups. Its visionary leaders included Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Josef Albers.

Annelise Fleischmann Albers (1899–1994) arrived at the avant-garde school as a student in 1922. She had been raised in a well-to-do Berlin household, and had hoped to continue to study painting, but that path was closed to her because of her gender. She took the preliminary courses, one of which was taught by the great color theorist Johannes Itten, and then entered the weaving workshop, reluctantly, as she recalled: “My beginning was far from what I had hoped for: fate put into my hands limp threads! Threads to build a future? But distrust turned into belief and I was on my way.” [1] Later, Klee was one of the instructors in the weaving workshop, and he became her mentor.

In 1925, she married Josef Albers who had started as a student in the glass workshop, and had been promoted to junior Bauhaus Master. That same year they moved with the school to Dessau into a modernistic home designed by Gropius. Through her textiles, Anni Albers advocated for change: “The traditional way of living is an outmoded machine that makes a woman into a slave of the home. Poor arrangement of rooms and furnishings (seat cushions, curtains) take her freedom away and thereby create nervousness and limited possibilities of development.” [2] In various commissions, she excelled at problem solving, for instance, replacing velvet with a new cellophane-like material that had the same ability to absorb sound.

With its funding undermined and its position threatened by the National Socialist Party, the Bauhaus closed in 1933, and the Alberses were without jobs in an environment hostile to artists. Anni was additionally at risk because of her Jewish heritage. When an invitation prompted by Philip Johnson came to join the faculty of Black Mountain College outside of Asheville, North Carolina, they accepted. An experimental school not unlike the Bauhaus, Black Mountain attracted many notable mid-century artists including Elaine and Willem de Kooning as faculty, and Kenneth Noland and Robert Rauschenberg as students. Anni was appointed Assistant Professor of Art and established a curriculum in textiles. She also made innovative jewelry from hairpins, paper clips, and curtain rings.

After sixteen years in western North Carolina, Josef and Anni Albers moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where he became chairman of the design department at Yale University. She taught a few seminars for architectural students and worked on commissions such as the bedspreads and partitions for the Gropius-designed dormitories at the Harvard Law School. Other architects came to admire her work, including Buckminster Fuller who stated, “Anni Albers, more than any other weaver, has succeeded in exciting mass realization of the complex structure of fabrics. She has brought the artist’s intuitive sculpturing faculties and the agelong weaver’s art into [a] historical successful marriage.” [3]

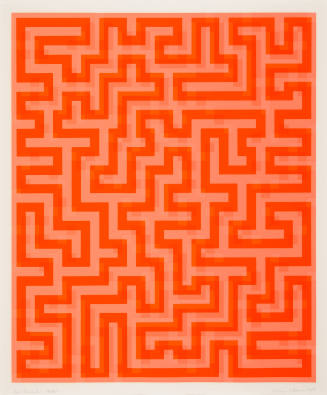

In 1963, Anni Albers turned to printmaking, and by 1970 had given up textiles in favor of prints. She explained, “I could not stand the idea anymore of all the yarns and looms. It took too long and it always produced just one piece. … I just outgrew it in some way. It annoyed me and I can’t do it anymore.” [4] In 1971, her husband established The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation for which she purchased woodland acreage in Bethany, Connecticut, with funds acquired by the restitution of family property in the former East Berlin. The mission of the foundation is to insure that their legacy and aesthetic vision endure.

Notes:

[1] Anni Albers, interview by Sigrid Wortmann Weltge, February 21, 1987, Orange, CT, transcript, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation archives, quoted in Nicholas Fox Weber and Pandora Tabatabai Asbaghi, Anni Albers (New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1999), 156.

[2] Anneliese Fleischmann, “Wohnoekonomie,” Neue Frauenkleidung und Frauenkultur, Karlsruhe, 1924, quoted in Nicholas Fox Weber and Martin Filler, Josef + Anni Albers: Designs for Living (London: Merrell Publishers, Limited, in association with Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, 2004), 153.

[3] Fuller, in book jacket for Anni Albers, On Designing (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1962), quoted in Weber, Josef + Anni Albers, 25.

[4] Anni Albers, interview with Maximillian Schell, December 16, 1978, Orange, CT, transcript, The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation archives, quoted in Asbaghi, Anni Albers, 177.