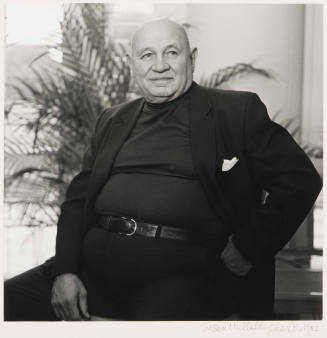

Romare Bearden

The celebrated African American modernist and collage artist Romare Bearden (1911–1988) took great inspiration from music. He often made musicians the subject of his art, but music inspired his form and style as well. He said, “I listened for hours to recordings of Earl Hines at the piano. Finally, I was able to concentrate on the silences between the notes. I found this was very helpful to me in the transmutation of sound into colors and in the placement of objects in my paintings and collages. I could have studied this integration and spacing in Greek vase painting … but with Earl Hines I ingested it within my own background. Jazz has shown me the ways of achieving artistic structures that are personal to me, but it also provides me continuing finger-snapping, head-shaking enjoyment.” [1]

Bearden was born in Charlotte, North Carolina, but moved with his family to New York as a young child. [2] The family settled in Harlem. His parents were both college-educated, and they became prominent members of the African American community in Harlem. His mother eventually became the editor of the Chicago Defender, an African American newspaper. Bearden grew up surrounded by noted members of the Harlem Renaissance: musician Duke Ellington, poet Langston Hughes, and sculptor Augusta Savage. Although New York remained his home for the rest of his life, Bearden frequently traveled during his childhood to visit grandparents in Pittsburgh and back to rural North Carolina to see relatives.

The artist recounts that a childhood friend in Pittsburgh first taught him how to draw. In college, he took classes in art and applied his drawing skills to producing political cartoons. He also began painting, taking night classes with the painter and graphic artist George Grosz at the Art Students League. He graduated from New York University in 1935 with a degree in education and became a caseworker for the New York City Department of Social Services. He supported himself in this position off and on, sometimes full-time, until 1969.

Bearden served in the military during World War II and was posted to several different locations across the United States. He continued painting; he had his first solo exhibition at a Harlem gallery in 1940 and subsequent shows in a gallery in Washington, D.C. In 1945, he began exhibiting with the Samuel Kootz Gallery in Manhattan. His work at the time depicted African American life in a decidedly modernist, Cubist-inspired style, evident in The Family, 1941, collection of Earle Hyman. In 1950, he went to Paris on the G.I. Bill, and studied at the Sorbonne and traveled to Italy. He painted little in France, but he visited museums enthusiastically and frequented cafés with other American expatriate artists and writers. He recalled seeing Henri Matisse pass by one day and expressed his pleasure when the waiters and customers greeted the aged artist with wild applause.

The 1950s was a troubled time for the artist; he was briefly hospitalized in 1956. In an attempt to earn money to return to Paris, he temporarily abandoned painting to try his hand at composing music. In remarks that he made at Reynolda House in 1982, he recalled, “When I came back [from Paris], I had a studio that used to be a rehearsal hall for the Apollo Theater. It had a piano, and I wanted to get back to Paris, so I said, ‘I’ll sit down and write a hit song, like Irving Berlin or Cole Porter.’ Of course, I didn’t know how to play the piano. But if you don’t think this way, there’s no use being an artist!” [3] He actually penned a hit, “Sea Breeze,” which was recorded by Dizzy Gillespie and Billy Eckstine. But the urge to paint was too strong to resist, and he returned to art with new enthusiasm, experimenting with abstraction and making his first collages.

In 1963, Bearden and several other African American artists formed a group called Spiral to discuss ways they as artists could engage with the Civil Rights movement. Bearden suggested that they collaborate on a collective collage. The idea led him to explore the medium more extensively in his own work, taking images from magazines and newspapers and combining them with paper and paint to create dynamic depictions of contemporary African American life. He also began making black and white Photostat enlargements of his collages, and he exhibited these, called Projections, at Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in 1964. The Street, 1964, Estate of Romare Bearden, is one of these works. The exhibition was well reviewed, representing the first serious critical attention Bearden received.

From the mid-1960s on, collage became Bearden’s primary medium. He created gritty, rhythmic compositions depicting the lives of African Americans as he observed them in New York City; Spring Way, 1964, Smithsonian American Art Museum, is a good example. He also returned to North Carolina and drew on the lives of rural African Americans in their small houses and on the farm, evident in Watching the Good Trains Go By, 1964, Columbus Museum of Art. Recurring motifs in his collages include huge staring eyes, large hands, trains, suns and moons, “conjur” or healing women, music and musicians, and animals of all kinds. He often drew on sources from history, literature, religion, and the art of the Renaissance and Baroque. His collages combine images from popular magazines with colored paper and paint; occasionally, as in his 1977 series based on Homer’s Odyssey, he eschewed the magazine cut-outs in favor of figures and images created just from intricately cut paper. He also experimented with other media as well, creating watercolors and prints, which were sometimes based on earlier collages, a process he compared to the “call-and-response” form of the Negro spiritual.

Bearden was passionately committed to advancing African American causes. His experiments with the Photostat process, which produced a negative version of an image, inspired him to begin turning white figures black, as he did with all of the Homeric characters in his Odyssey series. He also took Old Master paintings and re-imagined them with black figures instead of white, asking his viewers to affirm the universality of both art and human existence. With his friend Harry Henderson, he wrote A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present.

In 1973, Bearden and his wife Nanette built a home on the island of Saint Martin, where her family originated. They divided their time between their Caribbean home and New York, where his work continued to draw accolades. He was the subject of large retrospective exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in 1971, at the Mint Museum in Charlotte in 1980, and at the North Carolina Museum of Art in 1988. In 1987, he received the National Medal of the Arts. He died in 1988; fifteen years later, a large-scale retrospective at the National Gallery of Art helped to cement his reputation as one of the most important twentieth-century American modernists.

Notes:

[1] Bearden, quoted in “The Art of Romare Bearden: A Resource for Teachers,” http://www.nga.gov/education/classroom/bearden/musac3.shtm

[2] See Ruth Fine, et al The Art of Romare Bearden. Exhibition catalogue, (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2003).

[3] Transcript of videotaped remarks made by Bearden at Reynolda House in October 1982. Archives, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.