Skip to main contentBiographyShusaku Arakawa (1936–2010) was a Japanese-born artist and architect whose work in several media reflected his interests in philosophy and Dada, the early twentieth-century movement that rejected the conventional appreciation of culture. Always something of an enigma, Arakawa could be simultaneously intellectual and impractical. When World War II began, seven-year-old Arakawa was sent with other children to live in a Buddhist monastery and there experienced deprivation so great that he became severely malnourished and almost blind. He suffered from terrible nightmares when he returned to his village after the war.

Arakawa studied medicine and mathematics at the University of Tokyo before attending the Musashino art school for three years. He held his first exhibition of art in Tokyo in 1958, and soon became involved with a group of Neo-Dadaists who scandalized the city with their socially critical installations. After Arakawa had taken part in a demonstration against the United States’ military presence in Japan, concerned friends thought that he should leave the country and gave him the necessary funds to emigrate to the United States in 1961. In New York City, he moved into Yoko Ono’s loft and met members of the avant-garde, most importantly the artist Marcel Duchamp and the composer John Cage. Arakawa became increasingly interested in the function of language. A series of paintings called Diagrams consisted of everyday objects such as tennis rackets, combs, and gloves. In other paintings, the artist began to experiment with text, moving away from the objects themselves, replacing the silhouettes with faint outlines, and labeling the drawings with the names of the objects. He also began experimenting with notions of representation and the unreliability of language by labeling an object with an incorrect word, then visibly “erasing” it and replacing it with the correct one. Arakawa’s wife, Madeline Gins, whom he met in 1963 and married in 1966, is a writer and long-time collaborator with Arakawa. They wrote ten books together, including The Mechanism of Meaning, 1971, which is also the title of an ambitious series of nearly one hundred paintings in which Arakawa and Gins investigated thought processes, symbols, and language.

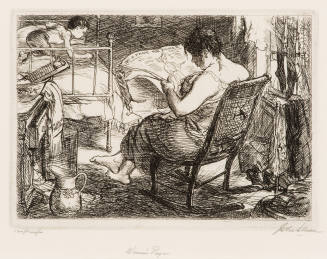

Arakawa’s experiences during the war and his familiarity with death and dead bodies may have fueled his interest, shared by Gins, in mortality. They wrote Reversible Destiny: We Have Decided Not To Die in 1997, and their last book, published in 2006, is called Making Dying Illegal. Arakawa and Gins’ work over the years increasingly focused on the creation of architecture that would promote their theory of reversible mortality. They designed buildings that were highly unorthodox in structure as well as design; they were meant to promote anti-ageing by stimulating and challenging residents out of their comfort zones. Arakawa’s prints and paintings can be appreciated solely for their subtle beauty and consummate mastery of technique, but the ultimate goal of these esoteric works may be to stimulate and challenge viewers into new ways of thinking and being.

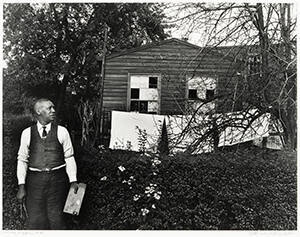

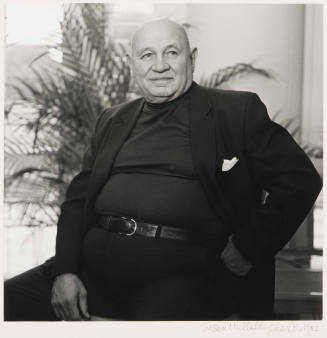

Shusaku Arakawa

1936 - 2010

Arakawa studied medicine and mathematics at the University of Tokyo before attending the Musashino art school for three years. He held his first exhibition of art in Tokyo in 1958, and soon became involved with a group of Neo-Dadaists who scandalized the city with their socially critical installations. After Arakawa had taken part in a demonstration against the United States’ military presence in Japan, concerned friends thought that he should leave the country and gave him the necessary funds to emigrate to the United States in 1961. In New York City, he moved into Yoko Ono’s loft and met members of the avant-garde, most importantly the artist Marcel Duchamp and the composer John Cage. Arakawa became increasingly interested in the function of language. A series of paintings called Diagrams consisted of everyday objects such as tennis rackets, combs, and gloves. In other paintings, the artist began to experiment with text, moving away from the objects themselves, replacing the silhouettes with faint outlines, and labeling the drawings with the names of the objects. He also began experimenting with notions of representation and the unreliability of language by labeling an object with an incorrect word, then visibly “erasing” it and replacing it with the correct one. Arakawa’s wife, Madeline Gins, whom he met in 1963 and married in 1966, is a writer and long-time collaborator with Arakawa. They wrote ten books together, including The Mechanism of Meaning, 1971, which is also the title of an ambitious series of nearly one hundred paintings in which Arakawa and Gins investigated thought processes, symbols, and language.

Arakawa’s experiences during the war and his familiarity with death and dead bodies may have fueled his interest, shared by Gins, in mortality. They wrote Reversible Destiny: We Have Decided Not To Die in 1997, and their last book, published in 2006, is called Making Dying Illegal. Arakawa and Gins’ work over the years increasingly focused on the creation of architecture that would promote their theory of reversible mortality. They designed buildings that were highly unorthodox in structure as well as design; they were meant to promote anti-ageing by stimulating and challenging residents out of their comfort zones. Arakawa’s prints and paintings can be appreciated solely for their subtle beauty and consummate mastery of technique, but the ultimate goal of these esoteric works may be to stimulate and challenge viewers into new ways of thinking and being.

Person TypeIndividual