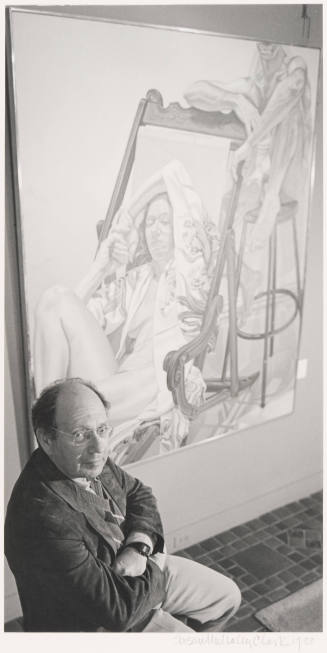

Skip to main contentBiographySince the development of photography in the nineteenth century, artists have used photographs in various ways to aid in the creation of paintings. In the 1970s, however, a group of artists began basing their work very deliberately on photographs, painstakingly recreating in paint the minute details captured in photographs. One of the original Photorealist painters of the 1970s, Ben Schonzeit creates still life paintings of astonishing illusionistic skill. The artist says, “I don’t paint pictures of things. I build things in paintings. I’m seriously attracted to the communication of visual experience, and that means reality.” [1]

Schonzeit, a native New Yorker, still lives and works in the city. He was born in Brooklyn in 1942. In 1960, he entered the Cooper Union, intending to study architecture, but his focus soon shifted to painting. When he graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1964, he was working in an abstract style, but within a few years felt the impact of Pop art. The artist described this influence on the development of Phototrealism: “Somewhere around 1970, the early 1970s, Lou Meisel came up with the word Photorealism. And at that time there were a lot of people working with photographs. I think the impetus for the work was Post-Pop. [James] Rosenquist, Andy Warhol, [Robert] Rauschenberg were all using photographs in their work. The next generation of painters started taking photographs seriously as source materials and painting paintings that looked very much like photographs. The movement started in 1970 or 1972. There were artists in New York and a lot of people in California. In New York, there was me, Chuck Close, Malcolm Morley, Robert Cottingham, Tom Blackwell, Ron Kleeman, Don Eddy.” [2] Audrey Flack, Robert Bechtle, Ralph Goings, and Richard Estes were also considered part of the Photorealist movement.

Pop art, with its cool, detached observations on popular culture, was seen as a reaction to the emotional spontaneity of Abstract Expressionism. Pop also reintroduced representation into art. The Photorealists took the emotional distance of the Pop artists one step further. By basing their paintings on photographs, they completely removed the possibility of spontaneous expression. The artist knew from the outset what the painting would look like. Critics of Photorealism dismiss it as mere imitation, suggesting that the artists are technical virtuosos with little depth or imagination.

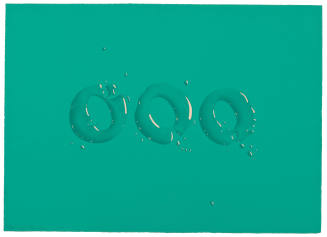

Many Photorealist painters take the photographs on which they base their paintings; some select random images from magazines or newspapers. In his Photorealist work, Schonzeit takes the photographs himself. He says, “The reason I use my own photographs is that my photographs are different from anyone else’s photographs. I take pictures looking for certain spatial qualities, certain colors.” [3] Using a projector he magnifies the image onto a canvas and recreates it in paint. He is a skilled manipulator of acrylic paint and the airbrush gun, and his paintings have a smooth, almost glass-like surface.

With Cottingham and Morley, Schonzeit was invited in 1972 to participate in the Dokumenta 5 exhibition in Kassel, Germany, that introduced Photorealism to the world. His work in the 1970s often centered around enlarged, radically cropped images of food: tangerines, painted with shiny white highlights and an exacting attention to detail; heads of cauliflower wrapped in plastic, ready for supermarket sale; rhubarb; crab legs; salads; cabbages; cupcakes. His Mackerel from 1973, in the collection of the Art Appreciation Association, recalls seventeenth-century Dutch still lifes of bountiful meals. The artist also paints trinkets, plastic figurines, paintbrushes, pens, shoes, keys, and tools. In some of his most original paintings, objects such as fruit seem to float across the surface of the canvas, rendered in sharp focus, while unrelated objects, such as a tray of watercolors, appear out of focus in the background.

Schonzeit’s loss of his left eye in a childhood accident affects both the square shape of his paintings and his unorthodox approaches to focus and perspective. He says, “My eye shapes my work. I have one eye, I lost my eye when I was five years old fooling around with a very sharp object. I perceive depth differently from other people. I also have a narrower peripheral vision than other people, so I tend to see squares. Partially how I determine where things are in space has to do with focus. If I look at you, what’s behind you goes out of focus because [my] brain doesn’t accept it. I’ve used that element, it’s become part of my work, because that’s how I see. I’m fascinated with how things appear.” [4]

Since the 1970s, Schonzeit has branched out from Photorealism, experimenting with composite, or, as he calls them, “layered” images. His recent brightly-hued floral still lifes have a fantastic, surreal quality to them. For a 2012 show entitled Edibles at Jonathan Novak gallery in Los Angeles, Schonzeit returned to the closely observed images of fruits and vegetables that characterized his Photorealist work. He has participated in significant solo and group shows at galleries and museums, and his work is represented in the collection of institutions such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Denver Art Museum, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, and the Basel Kunstmuseum. A major exhibition at the Guggenheim in Berlin in 2009 entitled Picturing America: Photorealism from the 1970s featured his painting Cauliflower, from the collection of Toni and Martin Sosnoff.

Notes:

[1] Charles A. Riley, “Color Magic,” WeMedia 4, no. 6 (November–December 2000), 74.

[2] Schonzeit interview, CP On Air Network Classic Talk with Bing and Dennis: Ben Schonzeit, October 14, 2011 http://www.cpli.com/cponair/cpli_4217.html#.

[3] Schonzeit interview.

[4] Schonzeit interview.

Ben Schonzeit

born 1942

Schonzeit, a native New Yorker, still lives and works in the city. He was born in Brooklyn in 1942. In 1960, he entered the Cooper Union, intending to study architecture, but his focus soon shifted to painting. When he graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1964, he was working in an abstract style, but within a few years felt the impact of Pop art. The artist described this influence on the development of Phototrealism: “Somewhere around 1970, the early 1970s, Lou Meisel came up with the word Photorealism. And at that time there were a lot of people working with photographs. I think the impetus for the work was Post-Pop. [James] Rosenquist, Andy Warhol, [Robert] Rauschenberg were all using photographs in their work. The next generation of painters started taking photographs seriously as source materials and painting paintings that looked very much like photographs. The movement started in 1970 or 1972. There were artists in New York and a lot of people in California. In New York, there was me, Chuck Close, Malcolm Morley, Robert Cottingham, Tom Blackwell, Ron Kleeman, Don Eddy.” [2] Audrey Flack, Robert Bechtle, Ralph Goings, and Richard Estes were also considered part of the Photorealist movement.

Pop art, with its cool, detached observations on popular culture, was seen as a reaction to the emotional spontaneity of Abstract Expressionism. Pop also reintroduced representation into art. The Photorealists took the emotional distance of the Pop artists one step further. By basing their paintings on photographs, they completely removed the possibility of spontaneous expression. The artist knew from the outset what the painting would look like. Critics of Photorealism dismiss it as mere imitation, suggesting that the artists are technical virtuosos with little depth or imagination.

Many Photorealist painters take the photographs on which they base their paintings; some select random images from magazines or newspapers. In his Photorealist work, Schonzeit takes the photographs himself. He says, “The reason I use my own photographs is that my photographs are different from anyone else’s photographs. I take pictures looking for certain spatial qualities, certain colors.” [3] Using a projector he magnifies the image onto a canvas and recreates it in paint. He is a skilled manipulator of acrylic paint and the airbrush gun, and his paintings have a smooth, almost glass-like surface.

With Cottingham and Morley, Schonzeit was invited in 1972 to participate in the Dokumenta 5 exhibition in Kassel, Germany, that introduced Photorealism to the world. His work in the 1970s often centered around enlarged, radically cropped images of food: tangerines, painted with shiny white highlights and an exacting attention to detail; heads of cauliflower wrapped in plastic, ready for supermarket sale; rhubarb; crab legs; salads; cabbages; cupcakes. His Mackerel from 1973, in the collection of the Art Appreciation Association, recalls seventeenth-century Dutch still lifes of bountiful meals. The artist also paints trinkets, plastic figurines, paintbrushes, pens, shoes, keys, and tools. In some of his most original paintings, objects such as fruit seem to float across the surface of the canvas, rendered in sharp focus, while unrelated objects, such as a tray of watercolors, appear out of focus in the background.

Schonzeit’s loss of his left eye in a childhood accident affects both the square shape of his paintings and his unorthodox approaches to focus and perspective. He says, “My eye shapes my work. I have one eye, I lost my eye when I was five years old fooling around with a very sharp object. I perceive depth differently from other people. I also have a narrower peripheral vision than other people, so I tend to see squares. Partially how I determine where things are in space has to do with focus. If I look at you, what’s behind you goes out of focus because [my] brain doesn’t accept it. I’ve used that element, it’s become part of my work, because that’s how I see. I’m fascinated with how things appear.” [4]

Since the 1970s, Schonzeit has branched out from Photorealism, experimenting with composite, or, as he calls them, “layered” images. His recent brightly-hued floral still lifes have a fantastic, surreal quality to them. For a 2012 show entitled Edibles at Jonathan Novak gallery in Los Angeles, Schonzeit returned to the closely observed images of fruits and vegetables that characterized his Photorealist work. He has participated in significant solo and group shows at galleries and museums, and his work is represented in the collection of institutions such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Denver Art Museum, the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, and the Basel Kunstmuseum. A major exhibition at the Guggenheim in Berlin in 2009 entitled Picturing America: Photorealism from the 1970s featured his painting Cauliflower, from the collection of Toni and Martin Sosnoff.

Notes:

[1] Charles A. Riley, “Color Magic,” WeMedia 4, no. 6 (November–December 2000), 74.

[2] Schonzeit interview, CP On Air Network Classic Talk with Bing and Dennis: Ben Schonzeit, October 14, 2011 http://www.cpli.com/cponair/cpli_4217.html#.

[3] Schonzeit interview.

[4] Schonzeit interview.

Person TypeIndividual