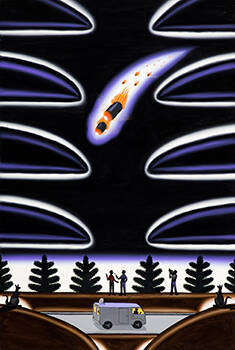

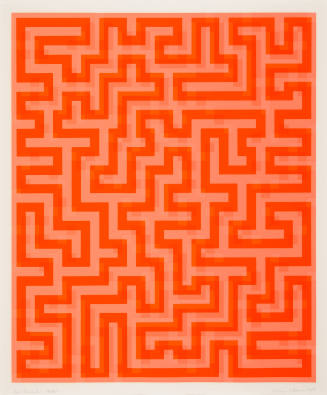

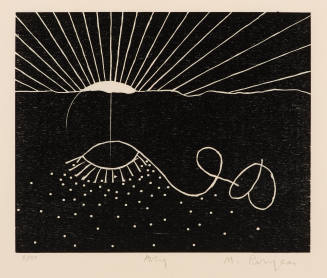

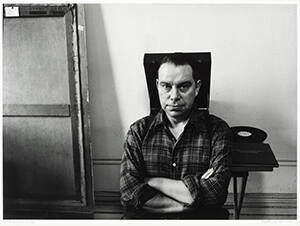

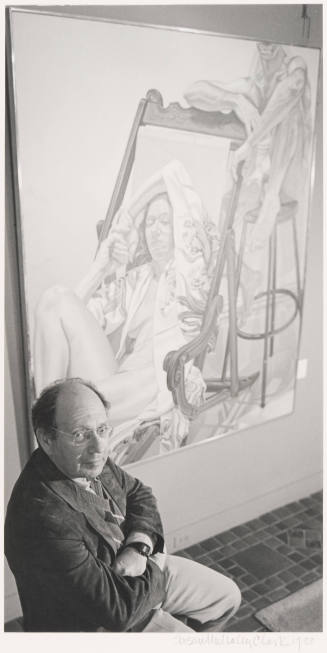

Skip to main contentBiographyAmerican art history is dominated by “schools”—Hudson River, Ashcan—and by movements—Impressionism, Regionalism, and Abstract Expressionism. Some artists work outside these trends, pursuing their own distinctive paths. Such is the case with Philip Evergood (1901–1973), who is often grouped with the social realists, probably because he was a realist painter who embraced socialism, and because he frequently commented on social issues. But his art is frequently fantastic and imaginary, with exaggerated colors and, sometimes, grotesque figures.

Evergood was born Philip Blashki in New York City in 1901; he attended the Ethical Culture School as a child. Early on, he displayed an interest in music and art, perhaps because his father was a landscape painter. His mother was English, and, for that reason, in 1909 he was sent to boarding schools in Sussex and Essex where he studied classics, religion, and geometry. After taking his mother’s name, from 1915 to 1919, he studied at Eton College, followed by a year at Trinity Hall College at Cambridge University. Later he declared, “I felt I ought to leave Cambridge and go in for art, that art was the only thing I had in my veins, inherited from my father.” [1]

Upon his decision to become an artist, in 1921 Evergood enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art in London and graduated two years later with a teaching certificate. He returned to New York, took classes at the Art Students League, then left for Paris where he studied briefly with Jean Paul Laurens. The next several years were divided between Paris, New York, and travels abroad. He finally settled in New York in 1931.

Evergood was befriended by the noted Ashcan School artist John Sloan, who introduced him to the administrators of the Public Works of Art Project, one of the New Deal programs, which he joined in 1933. Subsequently he was assigned to the mural division and completed a commission for the Richmond Hill Public Library in Queens, which created some controversy due to its scantily clad female figures. In 1937, Evergood served as president of the American Artists Union, an organization with socialist leanings. The following year, he was appointed managing supervisor of the easel division of the New York WPA Art Project. In the early forties, he was an artist-in-residence at Kalamazoo College in Michigan; he also taught at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, for one year.

John Sloan furthered Evergood’s career by offering advice; in addition, he purchased Evergood’s The Old Wharf, 1934, and donated it to the Brooklyn Museum. In appreciation, Evergood wrote flatteringly to his mentor: “To be represented in the permanent collection of so important a museum is honor enough, but the fact that so great an artist as you, whose work I have looked up to as being at the top art of our age, whose judgments in matters of art I have the deepest respect for, and whose advice and sympathetic criticism helped me to paint better and inspired me to go on, should be the instrument of the first acquisition of my work by an important museum, makes the honor doubly important to me, and doubly significant to me as a milestone in my career.” [2]

In the late 1930s, Evergood’s other great benefactor emerged: Joseph Hirshhorn, the eccentric financier and collector who gave his collection to the nation in 1966. Hirshhorn encountered Evergood trying to make ends meet by working in a frame shop. The painter recalled their first meeting: “After a short conversation, Hirshhorn called me away into the next room, and he said, ‘Evergood, I’ve seen your work at the Whitney annuals. I think you are a good painter. You shouldn’t be giving your energies to this sort of thing.’” [3] Hirshhorn then invited him to his apartment, telling him to bring ten canvases. On that occasion he purchased seven and eventually acquired more than sixty more for his collection. Even though they were at odds politically—Hirshhorn the capitalist, Evergood, the socialist—they still became friends, and Hirshhorn offered investment advice from which the artist benefited.

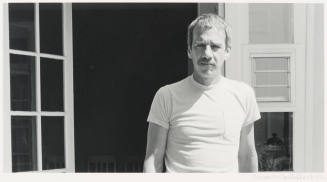

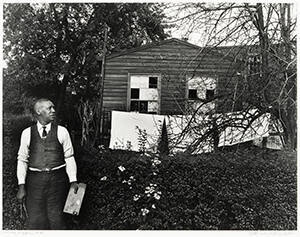

Evergood enjoyed a modicum of success, with regular showings at such well-known galleries as Montross, ACA, Dintenfass, Hammer, and Kennedy. In 1960, John I. H. Baur mounted a retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. According to Abram Lerner, the first director of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Evergood was reclusive and “did have a propensity for calamity, illnesses, and accidents that plagued him all his adult life. But he was by nature, at least outwardly, cheerful and optimistic.”[4]

As inspiration for his work, Evergood looked to Amedeo Modigliani and Jules Pascin for their handling of figures, and also the German Expressionist Max Beckmann, with whom he shared a fondness for dark outlines. Often the target of critics, Evergood responded by saying: “In discussing a ‘primitive’ and ‘folksy’ and ‘naïve’ quality in my paintings, they are quick to judge me by what they have read about my history. I’ve been called ‘the most sophisticated innocent in the world.’ Some have gone so far as to suggest that I am putting on some kind of ‘act,’ some sort of deception on the innocent public—all because I really am simple, direct, and natural in my approach to people and my life.” [5]

Notes:

[1] Evergood interview with John I.H. Baur, Philip Evergood (New York: Abrams, 1978), 21.

[2] Evergood to Sloan, undated draft, Evergood Papers, Archives of American Art, quoted in Kendall Taylor, Philip Evergood: Never Separate from the Heart (London and Toronto: Bucknell University Press and Associated University Presses, 1986), 84.

[3] Evergood interview with Forrest Selvig, December 3, 1968, Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-philip-evergood-12410.

[4] Lerner to Linda T. Long, December 23, 1986, Reynolda House Museum of American Art archives.

[5] Evergood interview with Lucy Lippard, The Graphic Work of Philip Evergood: Selected Drawings and Complete Prints (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1966).

Philip Evergood

1901 - 1973

Evergood was born Philip Blashki in New York City in 1901; he attended the Ethical Culture School as a child. Early on, he displayed an interest in music and art, perhaps because his father was a landscape painter. His mother was English, and, for that reason, in 1909 he was sent to boarding schools in Sussex and Essex where he studied classics, religion, and geometry. After taking his mother’s name, from 1915 to 1919, he studied at Eton College, followed by a year at Trinity Hall College at Cambridge University. Later he declared, “I felt I ought to leave Cambridge and go in for art, that art was the only thing I had in my veins, inherited from my father.” [1]

Upon his decision to become an artist, in 1921 Evergood enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art in London and graduated two years later with a teaching certificate. He returned to New York, took classes at the Art Students League, then left for Paris where he studied briefly with Jean Paul Laurens. The next several years were divided between Paris, New York, and travels abroad. He finally settled in New York in 1931.

Evergood was befriended by the noted Ashcan School artist John Sloan, who introduced him to the administrators of the Public Works of Art Project, one of the New Deal programs, which he joined in 1933. Subsequently he was assigned to the mural division and completed a commission for the Richmond Hill Public Library in Queens, which created some controversy due to its scantily clad female figures. In 1937, Evergood served as president of the American Artists Union, an organization with socialist leanings. The following year, he was appointed managing supervisor of the easel division of the New York WPA Art Project. In the early forties, he was an artist-in-residence at Kalamazoo College in Michigan; he also taught at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania, for one year.

John Sloan furthered Evergood’s career by offering advice; in addition, he purchased Evergood’s The Old Wharf, 1934, and donated it to the Brooklyn Museum. In appreciation, Evergood wrote flatteringly to his mentor: “To be represented in the permanent collection of so important a museum is honor enough, but the fact that so great an artist as you, whose work I have looked up to as being at the top art of our age, whose judgments in matters of art I have the deepest respect for, and whose advice and sympathetic criticism helped me to paint better and inspired me to go on, should be the instrument of the first acquisition of my work by an important museum, makes the honor doubly important to me, and doubly significant to me as a milestone in my career.” [2]

In the late 1930s, Evergood’s other great benefactor emerged: Joseph Hirshhorn, the eccentric financier and collector who gave his collection to the nation in 1966. Hirshhorn encountered Evergood trying to make ends meet by working in a frame shop. The painter recalled their first meeting: “After a short conversation, Hirshhorn called me away into the next room, and he said, ‘Evergood, I’ve seen your work at the Whitney annuals. I think you are a good painter. You shouldn’t be giving your energies to this sort of thing.’” [3] Hirshhorn then invited him to his apartment, telling him to bring ten canvases. On that occasion he purchased seven and eventually acquired more than sixty more for his collection. Even though they were at odds politically—Hirshhorn the capitalist, Evergood, the socialist—they still became friends, and Hirshhorn offered investment advice from which the artist benefited.

Evergood enjoyed a modicum of success, with regular showings at such well-known galleries as Montross, ACA, Dintenfass, Hammer, and Kennedy. In 1960, John I. H. Baur mounted a retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. According to Abram Lerner, the first director of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Evergood was reclusive and “did have a propensity for calamity, illnesses, and accidents that plagued him all his adult life. But he was by nature, at least outwardly, cheerful and optimistic.”[4]

As inspiration for his work, Evergood looked to Amedeo Modigliani and Jules Pascin for their handling of figures, and also the German Expressionist Max Beckmann, with whom he shared a fondness for dark outlines. Often the target of critics, Evergood responded by saying: “In discussing a ‘primitive’ and ‘folksy’ and ‘naïve’ quality in my paintings, they are quick to judge me by what they have read about my history. I’ve been called ‘the most sophisticated innocent in the world.’ Some have gone so far as to suggest that I am putting on some kind of ‘act,’ some sort of deception on the innocent public—all because I really am simple, direct, and natural in my approach to people and my life.” [5]

Notes:

[1] Evergood interview with John I.H. Baur, Philip Evergood (New York: Abrams, 1978), 21.

[2] Evergood to Sloan, undated draft, Evergood Papers, Archives of American Art, quoted in Kendall Taylor, Philip Evergood: Never Separate from the Heart (London and Toronto: Bucknell University Press and Associated University Presses, 1986), 84.

[3] Evergood interview with Forrest Selvig, December 3, 1968, Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-philip-evergood-12410.

[4] Lerner to Linda T. Long, December 23, 1986, Reynolda House Museum of American Art archives.

[5] Evergood interview with Lucy Lippard, The Graphic Work of Philip Evergood: Selected Drawings and Complete Prints (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1966).

Person TypeIndividual