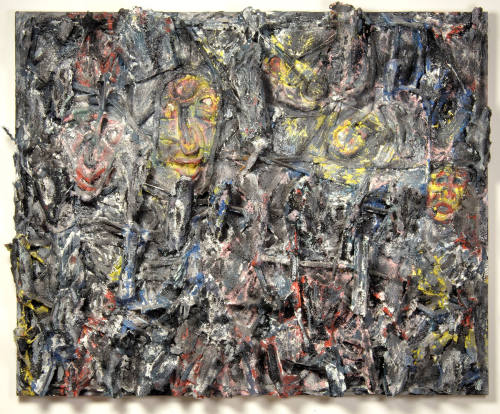

Skip to main contentBiographyIn the late twentieth century, artists working outside of the mainstream began to enjoy significant recognition. Instead of going to art schools, they mined their own heritage and surroundings to create distinctive works of art. In addition to their often-innovative techniques, these artists frequently conveyed special meanings through their work. As Thornton Dial (born 1928) declared: “You probably see many things in my art if you’re looking at it right.” [1]

Thornton Dial, Sr., is an important American artist who was born, raised, and lived in the Deep South his entire life. His birthplace was Emelle in Sumter County, Alabama, but he has resided and worked in Pipe Shop and Bessemer, on the outskirts of Birmingham, all his life. Dial was a “yard child,” in other words an illegitimate child, of white, Native American, and African ancestry. His teenage mother was unable and/or not inclined to raise him, so he was brought up first by his maternal great-grandmother in Emelle. Upon her death, he moved in with other relatives living in Bessemer, on the outskirts of Birmingham, then to Pipe Shop. As an adult, Dial built two houses for his wife and children in Pipe Shop.

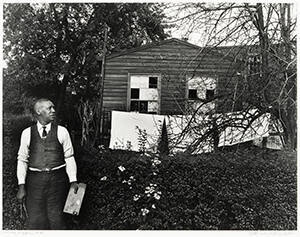

Throughout his life, Dial has been surrounded with multiple examples of the African American tradition of the “yard show” including his own, although before 1987 he kept much of what he created hidden. The yard show—the outdoor display of eclectic man and machine-made objects—would encompass areas considered sacred, whereas outside the yard would be considered “jungle.” [2]

Given the hurdles to attaining professional recognition as a fine artist—an impoverished African American in the segregated South, a limited formal education, blue collar occupation, not to mention a lack of access to art training and museums—Dial has leveraged his lower class roots to inform his compelling and unique voice in the contemporary art world. He has seen hard work and hard times. “I done most every kind of work a man can do. Cement work on the highways, pouring iron at Jones Foundry, loaded bricks at Harbison Walker brickyard, did some pipe fitting, worked down at the waterworks, did carpentry and house painting for different white contractors, metalwork—all kind of it—iron and steel at Pullman-Standard for about thirty years. I’m a working man.” [3] Dial expresses visually complex imagery and explores African American cultural practices in mixed media assemblages that offer a critique of contemporary society. He presents the viewer with uncomfortable evidence that violence and prejudices against African Americans, poor laborers, and women are very much a part of the world in which we all live and with which we are complicit.

Since the nineteenth century, African Americans who became expert steel mill workers got better wages than most of their counterparts in other industries, although they were paid less than whites and had the dirtiest and most dangerous duties in the factories. Thornton Dial worked for the Pullman-Standard Railcar Manufacturing Company for three decades, until the company shut down in the early 1980s. With his three sons, he then started the metal fabrication shop Dial Metal Patterns. The inventiveness and facility in working metal that Dial uses in his art was first honed on the factory floor, although he did not receive any acknowledgment from his employers. “I used to have all kinds of ideas for them that would help them be improving the plant. Had a lot of them. I drawed them out, how to do it, to explain it to them. Sometimes I turned them in, sometimes I told the supervisor my ideas. They always seemed to use my ideas—maybe three weeks, a month later—but they never said nothing to me about it. Not even, ‘Thank you, Dial.’” [4]

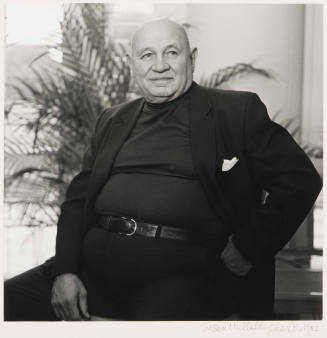

Dial has been an eyewitness to key developments in African American history, from the 1931 Scottsboro Case through the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, the AIDS epidemic, Rodney King and the Los Angeles riots, and Barack Obama’s election as the nation’s first president with African ancestry. Because of its ambitious scope and scale and variety of materials, Dial’s work defies easy categorization as folk, outsider, visionary, self-taught, or black Southern vernacular. However, it is clear that his success resulted from the patronage of William Arnett, a white businessman from Atlanta, Georgia, who was first introduced to Dial in 1987. Dial was reluctant to admit to being an artist, although he had been making pieces even before his departure from the factory. In addition to Dial, Arnett championed the women’s collective quilters of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. The problematic nature of what was seen as a quasi-paternalistic relationship between the younger white Arnett and the older African American Dial was the subject of a 1993 episode of Sixty Minutes. Morley Safer voiced skepticism about Dial’s meteoric rise in the art world and the resulting prices for his work, implying that Dial and other artists were mere pawns in Arnett’s scheme for fame and cash. The episode, which aired around the time of the opening of a one-man exhibition at the Museum of American Folk Art in New York, made Dial look as though he knew nothing of his own artistic and business affairs. Arnett, in contrast, was portrayed as a slick businessman. Dial was devastated, and other exhibitions planned by major museums were cancelled. Although in 1996 he had a one-man exhibition at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University, Atlanta, and he was included in an art exhibition for the Atlanta Olympics, both curated by Robert Hobbs, critical attention waned for more than a decade.

In the mid-1990s, William Arnett and others in his family started the Souls Grown Deep Foundation to ensure that the work of Dial and other Southern vernacular artists was preserved, documented, and exhibited. Throughout the period, Dial continued to make works in response to current events, shaped by his life experiences. In the second decade of the twenty-first century there seems to be a reevaluation and restoration of Dial’s reputation in the art world, led by the artist’s continued production of remarkable work and the sustained efforts of key critics and curators who recognize the strength of his aesthetic achievement. In 2011, the Indianapolis Museum of Art organized a travelling career retrospective, Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial, which has brought renewed attention to this American master.

As Dial himself claims, “I make art that ain’t speaking against nobody or for nobody either. Sometimes it be about what is wrong in life. I do that because I want the world to be right if people can see it and understand. It don’t make the world right just because I want it right. I hope that I can just make them study over it.” [5]

Notes:

[1] Dial quoted in Carol Kino, “Letting His Life’s Work Do the Talking,” The New York Times, February 17, 2011.

[2] Robert C. Hobbs in conversation with Kathleen F. G. Hutton, May 2008, notes in object file, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[3] Dial quoted in John Beardsley, “His Story/History,” in Thornton Dial in the Twentieth Century (Atlanta, GA: Tinwood Books in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2005), 281.

[4] Dial quoted in Beardsley, “His Story/History,” 282.

[5] Dial quoted in Lynda Hartigan, “Going Urban: American Folk Art and the Great Migration,” American Art 14, no. 2 (Summer 2000), 40.

Thornton Dial

American, 1928 - 2016

Thornton Dial, Sr., is an important American artist who was born, raised, and lived in the Deep South his entire life. His birthplace was Emelle in Sumter County, Alabama, but he has resided and worked in Pipe Shop and Bessemer, on the outskirts of Birmingham, all his life. Dial was a “yard child,” in other words an illegitimate child, of white, Native American, and African ancestry. His teenage mother was unable and/or not inclined to raise him, so he was brought up first by his maternal great-grandmother in Emelle. Upon her death, he moved in with other relatives living in Bessemer, on the outskirts of Birmingham, then to Pipe Shop. As an adult, Dial built two houses for his wife and children in Pipe Shop.

Throughout his life, Dial has been surrounded with multiple examples of the African American tradition of the “yard show” including his own, although before 1987 he kept much of what he created hidden. The yard show—the outdoor display of eclectic man and machine-made objects—would encompass areas considered sacred, whereas outside the yard would be considered “jungle.” [2]

Given the hurdles to attaining professional recognition as a fine artist—an impoverished African American in the segregated South, a limited formal education, blue collar occupation, not to mention a lack of access to art training and museums—Dial has leveraged his lower class roots to inform his compelling and unique voice in the contemporary art world. He has seen hard work and hard times. “I done most every kind of work a man can do. Cement work on the highways, pouring iron at Jones Foundry, loaded bricks at Harbison Walker brickyard, did some pipe fitting, worked down at the waterworks, did carpentry and house painting for different white contractors, metalwork—all kind of it—iron and steel at Pullman-Standard for about thirty years. I’m a working man.” [3] Dial expresses visually complex imagery and explores African American cultural practices in mixed media assemblages that offer a critique of contemporary society. He presents the viewer with uncomfortable evidence that violence and prejudices against African Americans, poor laborers, and women are very much a part of the world in which we all live and with which we are complicit.

Since the nineteenth century, African Americans who became expert steel mill workers got better wages than most of their counterparts in other industries, although they were paid less than whites and had the dirtiest and most dangerous duties in the factories. Thornton Dial worked for the Pullman-Standard Railcar Manufacturing Company for three decades, until the company shut down in the early 1980s. With his three sons, he then started the metal fabrication shop Dial Metal Patterns. The inventiveness and facility in working metal that Dial uses in his art was first honed on the factory floor, although he did not receive any acknowledgment from his employers. “I used to have all kinds of ideas for them that would help them be improving the plant. Had a lot of them. I drawed them out, how to do it, to explain it to them. Sometimes I turned them in, sometimes I told the supervisor my ideas. They always seemed to use my ideas—maybe three weeks, a month later—but they never said nothing to me about it. Not even, ‘Thank you, Dial.’” [4]

Dial has been an eyewitness to key developments in African American history, from the 1931 Scottsboro Case through the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, the AIDS epidemic, Rodney King and the Los Angeles riots, and Barack Obama’s election as the nation’s first president with African ancestry. Because of its ambitious scope and scale and variety of materials, Dial’s work defies easy categorization as folk, outsider, visionary, self-taught, or black Southern vernacular. However, it is clear that his success resulted from the patronage of William Arnett, a white businessman from Atlanta, Georgia, who was first introduced to Dial in 1987. Dial was reluctant to admit to being an artist, although he had been making pieces even before his departure from the factory. In addition to Dial, Arnett championed the women’s collective quilters of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. The problematic nature of what was seen as a quasi-paternalistic relationship between the younger white Arnett and the older African American Dial was the subject of a 1993 episode of Sixty Minutes. Morley Safer voiced skepticism about Dial’s meteoric rise in the art world and the resulting prices for his work, implying that Dial and other artists were mere pawns in Arnett’s scheme for fame and cash. The episode, which aired around the time of the opening of a one-man exhibition at the Museum of American Folk Art in New York, made Dial look as though he knew nothing of his own artistic and business affairs. Arnett, in contrast, was portrayed as a slick businessman. Dial was devastated, and other exhibitions planned by major museums were cancelled. Although in 1996 he had a one-man exhibition at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University, Atlanta, and he was included in an art exhibition for the Atlanta Olympics, both curated by Robert Hobbs, critical attention waned for more than a decade.

In the mid-1990s, William Arnett and others in his family started the Souls Grown Deep Foundation to ensure that the work of Dial and other Southern vernacular artists was preserved, documented, and exhibited. Throughout the period, Dial continued to make works in response to current events, shaped by his life experiences. In the second decade of the twenty-first century there seems to be a reevaluation and restoration of Dial’s reputation in the art world, led by the artist’s continued production of remarkable work and the sustained efforts of key critics and curators who recognize the strength of his aesthetic achievement. In 2011, the Indianapolis Museum of Art organized a travelling career retrospective, Hard Truths: The Art of Thornton Dial, which has brought renewed attention to this American master.

As Dial himself claims, “I make art that ain’t speaking against nobody or for nobody either. Sometimes it be about what is wrong in life. I do that because I want the world to be right if people can see it and understand. It don’t make the world right just because I want it right. I hope that I can just make them study over it.” [5]

Notes:

[1] Dial quoted in Carol Kino, “Letting His Life’s Work Do the Talking,” The New York Times, February 17, 2011.

[2] Robert C. Hobbs in conversation with Kathleen F. G. Hutton, May 2008, notes in object file, Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

[3] Dial quoted in John Beardsley, “His Story/History,” in Thornton Dial in the Twentieth Century (Atlanta, GA: Tinwood Books in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2005), 281.

[4] Dial quoted in Beardsley, “His Story/History,” 282.

[5] Dial quoted in Lynda Hartigan, “Going Urban: American Folk Art and the Great Migration,” American Art 14, no. 2 (Summer 2000), 40.

Person TypeIndividual