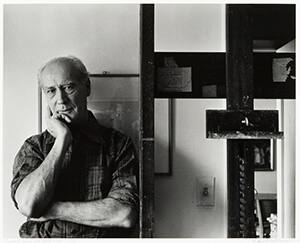

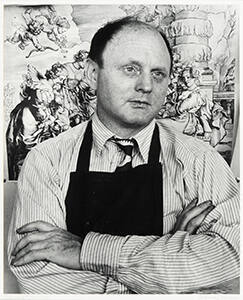

Skip to main contentBiographyIn the opening decades of the twentieth century, American sculpture was dominated by conventional classicism, especially in public monuments. A prime example of this trend is Daniel Chester French’s 1920 white marble statue of Abraham Lincoln for his memorial in Washington, D.C., an image as classical as the building in which it resides. In contrast, expatriate artist John Storrs (1885–1956) responded to the streamlined skyscrapers being erected in the country’s largest cities and developed a reputation for architectonic abstractions.

A native of Chicago, Storrs experienced firsthand the upsurge of modern urban architecture, particularly since his father was a successful architect and developer. At first, Storrs was educated at home by his mother, a watercolorist, and later in life he remembered visits to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition as an eight-year-old. He attended the John Dewey Experimental School for Progressive Education at the University of Chicago, and looking back he claimed it was there that he first learned how to see. His secondary education took place at the Chicago Manual Training School, well known for its interdisciplinary approach to the arts.

Storrs’s art education as an adult was wide-ranging: studies with Arthur Bock for six months in Hamburg, Germany, in 1905, followed by classes with Lorado Taft at the Art Institute of Chicago, Bela Pratt at the Boston Museum School, and Charles Grafly at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Enjoying financial support from his family, he spent a wanderjahre in 1907, traveling to Paris, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, Spain, and Greece. In 1912, he returned to Paris where he enrolled at the Académie Julian and then became a student and protégé of Auguste Rodin. Storrs assisted with the installation of the museum dedicated to the great French master, who encouraged the young American with this advice: “Now young man you can do anything you like, all you have to do is to go right ahead.” [1] After Rodin’s death in 1917, Storrs struck out on his own stylistically—creating sleekly modern and architectonic abstractions of metal, which earned him the sobriquet “Machine Age Modernist.”

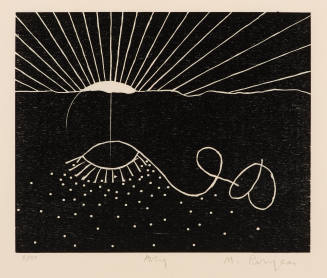

Married to a French woman, author and journalist Marguerite Chabrol, Storrs spent World War I in Paris working in a hospital. In 1917, he undertook a series of seventeen very stylized woodcuts to illustrate a deluxe edition of Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself. Storrs preferred living in France, even after the 1920 death of his father, who stipulated in his will that to retain his inheritance his son was to spend eight months each year in the United States. Frustrated by these restrictions, Storrs told an American reporter: “My work, at least in the immediate future, lies over there. It is there my inspiration lies. Paris is at the art center of the world and I refuse to jeopardize my career for any legal technicalities.” [2] Curiously, much of Storrs’s inspiration came from American architecture and Native American art, and for a while his art was more warmly received in the States than it was abroad.

To help fulfill the requirements of his father’s will, Storrs sought commissions in America, and succeeded with an impressive one for the Chicago Board of Trade in the late 1920s. The three-story figure of Ceres—the ancient goddess of agriculture—stands atop the noted Holabird & Root building, which reigned as the city’s tallest structure for thirty-five years. Storrs’s elegant Art Deco aluminum statue complements the building; the vertical folds of Ceres’s gown mirror the fluting of the building below her and achieve, according to Storrs, “architectural harmony with the building on which it was to stand.” [3]

Storrs’s first one-man exhibition in 1920 at the Folsom Gallery in New York challenged the tastes of his countrymen. He averred: “In America there is too much of the classic, and not enough of the Gothic. Too much of the horizontal, and not enough of the vertical. Too much of the cube and not enough of the pyramid. Too much of the box and not enough of the mountain peak.” [4] Ultimately, he determined to forfeit his inheritance and in 1930 purchased a fifteenth-century complex, the Chateau de Chantecaille, in the Loire Valley south of Orléans. When the Depression hit in the 1930s, Storrs turned to painting, which he continued in the early years of World War II when metals were both expensive and hard to procure. The Nazis imprisoned him for six months, an experience that severely impacted him both mentally and physically. He made his last visit to America in 1939, then retired to his chateau where he died seventeen years later.

Notes:

[1] Storrs quoted in http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/Exhibition-Catalogs-John-Storrs-Exhibitions--306331

[2] Storrs quoted in Debra Bricker Balken, John Storrs: Machine-Age Modernist (Boston, MA: The Boston Athenaeum, distributed by University Press of New England, 2010), 13.

[3] Storrs quoted in Philip Hampson, “Ancient Goddess in Modern Form to Command City,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, May 4, 1930, quoted in Jessica Wright, “Ceres and the Grain Trade from Sicily and North Africa to Chicago,” Classicizing Chicago http://www.classicizingchicago.northwestern.edu/node/1767.

[4] Storrs quoted in Balken, John Storrs, 33.

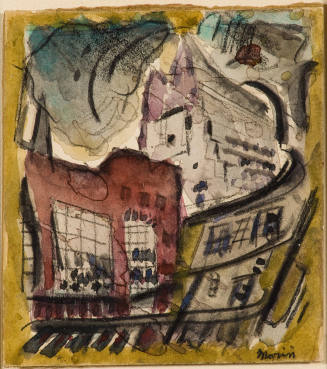

Image Not Available

for John Storrs

John Storrs

1885 - 1956

A native of Chicago, Storrs experienced firsthand the upsurge of modern urban architecture, particularly since his father was a successful architect and developer. At first, Storrs was educated at home by his mother, a watercolorist, and later in life he remembered visits to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition as an eight-year-old. He attended the John Dewey Experimental School for Progressive Education at the University of Chicago, and looking back he claimed it was there that he first learned how to see. His secondary education took place at the Chicago Manual Training School, well known for its interdisciplinary approach to the arts.

Storrs’s art education as an adult was wide-ranging: studies with Arthur Bock for six months in Hamburg, Germany, in 1905, followed by classes with Lorado Taft at the Art Institute of Chicago, Bela Pratt at the Boston Museum School, and Charles Grafly at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Enjoying financial support from his family, he spent a wanderjahre in 1907, traveling to Paris, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, Spain, and Greece. In 1912, he returned to Paris where he enrolled at the Académie Julian and then became a student and protégé of Auguste Rodin. Storrs assisted with the installation of the museum dedicated to the great French master, who encouraged the young American with this advice: “Now young man you can do anything you like, all you have to do is to go right ahead.” [1] After Rodin’s death in 1917, Storrs struck out on his own stylistically—creating sleekly modern and architectonic abstractions of metal, which earned him the sobriquet “Machine Age Modernist.”

Married to a French woman, author and journalist Marguerite Chabrol, Storrs spent World War I in Paris working in a hospital. In 1917, he undertook a series of seventeen very stylized woodcuts to illustrate a deluxe edition of Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself. Storrs preferred living in France, even after the 1920 death of his father, who stipulated in his will that to retain his inheritance his son was to spend eight months each year in the United States. Frustrated by these restrictions, Storrs told an American reporter: “My work, at least in the immediate future, lies over there. It is there my inspiration lies. Paris is at the art center of the world and I refuse to jeopardize my career for any legal technicalities.” [2] Curiously, much of Storrs’s inspiration came from American architecture and Native American art, and for a while his art was more warmly received in the States than it was abroad.

To help fulfill the requirements of his father’s will, Storrs sought commissions in America, and succeeded with an impressive one for the Chicago Board of Trade in the late 1920s. The three-story figure of Ceres—the ancient goddess of agriculture—stands atop the noted Holabird & Root building, which reigned as the city’s tallest structure for thirty-five years. Storrs’s elegant Art Deco aluminum statue complements the building; the vertical folds of Ceres’s gown mirror the fluting of the building below her and achieve, according to Storrs, “architectural harmony with the building on which it was to stand.” [3]

Storrs’s first one-man exhibition in 1920 at the Folsom Gallery in New York challenged the tastes of his countrymen. He averred: “In America there is too much of the classic, and not enough of the Gothic. Too much of the horizontal, and not enough of the vertical. Too much of the cube and not enough of the pyramid. Too much of the box and not enough of the mountain peak.” [4] Ultimately, he determined to forfeit his inheritance and in 1930 purchased a fifteenth-century complex, the Chateau de Chantecaille, in the Loire Valley south of Orléans. When the Depression hit in the 1930s, Storrs turned to painting, which he continued in the early years of World War II when metals were both expensive and hard to procure. The Nazis imprisoned him for six months, an experience that severely impacted him both mentally and physically. He made his last visit to America in 1939, then retired to his chateau where he died seventeen years later.

Notes:

[1] Storrs quoted in http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/Exhibition-Catalogs-John-Storrs-Exhibitions--306331

[2] Storrs quoted in Debra Bricker Balken, John Storrs: Machine-Age Modernist (Boston, MA: The Boston Athenaeum, distributed by University Press of New England, 2010), 13.

[3] Storrs quoted in Philip Hampson, “Ancient Goddess in Modern Form to Command City,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, May 4, 1930, quoted in Jessica Wright, “Ceres and the Grain Trade from Sicily and North Africa to Chicago,” Classicizing Chicago http://www.classicizingchicago.northwestern.edu/node/1767.

[4] Storrs quoted in Balken, John Storrs, 33.

Person TypeIndividual