Skip to main contentBiographyThe still life painter William Michael Harnett lived a relatively short life and rarely wrote about either his personal life or his art. Therefore, little documentation exists to construct an extensive biography. A few facts are known.

Harnett was born in Ireland in 1848, but moved with his family to Philadelphia as an infant. He was raised in Philadelphia and went to work as an engraver at the age of 17 in order to help support his family. In 1866, he began taking classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He moved to New York in 1869, continuing to work as an engraver, but also enrolling for classes at the National Academy of Design and the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art.

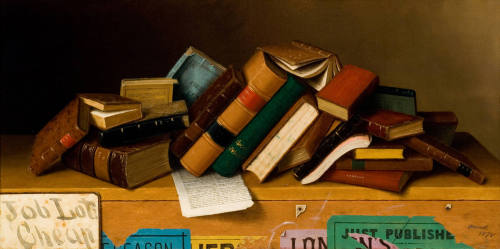

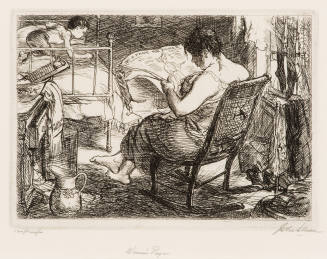

Harnett completed his first oil painting, entitled Paint Tube and Grapes, in 1874 at the age of 26. The next year, he began to exhibit his work, and he was able to give up engraving and devote himself fully to painting. In 1876, he returned to Philadelphia, enrolling again at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he met and befriended John Frederick Peto, another painter of illusionistic still lifes whose work would eventually be mistaken for Harnett’s. During the late 1870s, Harnett was occupied with study and with the exhibition of his work. His subjects at the time centered around fruit, books and newspapers, pipes and tobacco, currency and letters, quills and ink, and vanitas elements such as skulls, candlesticks, and hourglasses. The extraordinary illusionism of his work proved popular with art buyers; some of his most faithful patrons were wealthy dry goods merchants and department store owners. Critics, however, sometimes dismissed his work as simple imitation.

By 1880, Harnett had sold enough paintings to fund a trip to Europe. Between 1880 and 1886, he traveled, primarily in England, France, and Germany, settling for the longest period in Munich, a popular destination for American artists. In Munich, he continued to paint, exhibit, and sell his work. He produced his well-known series of paintings on the theme of the hunt during this period. The fact that his work, marked by extreme precision and detail, continued to find supporters in Europe is perhaps surprising considering the extraordinary attention the Impressionists were attracting at this time.

In 1886, Harnett returned to the United States and settled in New York. His subjects at the time often centered around music, focusing on instruments and sheet music. It was at this time, too, that Harnett’s extraordinary trompe-l’oeil talents proved troublesome. In 1886, Treasury agents seized one of Harnett’s remarkably realistic images of paper currency and accused him of counterfeiting bills. Following the advice of the judge who heard the case, Harnett abandoned currency as a subject of his painting.

The final years of Harnett’s life were marked by professional triumphs—the sale of one of his After the Hunt paintings for $4000, for example—but personal disappointments as well, mostly stemming from his poor health. The artist traveled for rest cures twice during this period, but he failed to see any significant improvement. He died in 1892 at the age of 44. An account of his life appeared just days later in the Dry Goods Economist, a testament to the faithfulness of his patrons in that field.

Harnett’s reputation faded over the next few decades, to be revived in the 1930s by the New York gallery owner Edith Halpert and the art critic Alfred Frankenstein. In 1939, Halpert held an exhibition entitled ‘Nature-Vivre’ by William M. Harnett in her Downtown Art Gallery, sparking new interest from critics, museums, and collectors in Harnett’s work.

William Michael Harnett

1848 - 1892

Harnett was born in Ireland in 1848, but moved with his family to Philadelphia as an infant. He was raised in Philadelphia and went to work as an engraver at the age of 17 in order to help support his family. In 1866, he began taking classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He moved to New York in 1869, continuing to work as an engraver, but also enrolling for classes at the National Academy of Design and the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art.

Harnett completed his first oil painting, entitled Paint Tube and Grapes, in 1874 at the age of 26. The next year, he began to exhibit his work, and he was able to give up engraving and devote himself fully to painting. In 1876, he returned to Philadelphia, enrolling again at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he met and befriended John Frederick Peto, another painter of illusionistic still lifes whose work would eventually be mistaken for Harnett’s. During the late 1870s, Harnett was occupied with study and with the exhibition of his work. His subjects at the time centered around fruit, books and newspapers, pipes and tobacco, currency and letters, quills and ink, and vanitas elements such as skulls, candlesticks, and hourglasses. The extraordinary illusionism of his work proved popular with art buyers; some of his most faithful patrons were wealthy dry goods merchants and department store owners. Critics, however, sometimes dismissed his work as simple imitation.

By 1880, Harnett had sold enough paintings to fund a trip to Europe. Between 1880 and 1886, he traveled, primarily in England, France, and Germany, settling for the longest period in Munich, a popular destination for American artists. In Munich, he continued to paint, exhibit, and sell his work. He produced his well-known series of paintings on the theme of the hunt during this period. The fact that his work, marked by extreme precision and detail, continued to find supporters in Europe is perhaps surprising considering the extraordinary attention the Impressionists were attracting at this time.

In 1886, Harnett returned to the United States and settled in New York. His subjects at the time often centered around music, focusing on instruments and sheet music. It was at this time, too, that Harnett’s extraordinary trompe-l’oeil talents proved troublesome. In 1886, Treasury agents seized one of Harnett’s remarkably realistic images of paper currency and accused him of counterfeiting bills. Following the advice of the judge who heard the case, Harnett abandoned currency as a subject of his painting.

The final years of Harnett’s life were marked by professional triumphs—the sale of one of his After the Hunt paintings for $4000, for example—but personal disappointments as well, mostly stemming from his poor health. The artist traveled for rest cures twice during this period, but he failed to see any significant improvement. He died in 1892 at the age of 44. An account of his life appeared just days later in the Dry Goods Economist, a testament to the faithfulness of his patrons in that field.

Harnett’s reputation faded over the next few decades, to be revived in the 1930s by the New York gallery owner Edith Halpert and the art critic Alfred Frankenstein. In 1939, Halpert held an exhibition entitled ‘Nature-Vivre’ by William M. Harnett in her Downtown Art Gallery, sparking new interest from critics, museums, and collectors in Harnett’s work.

Person TypeIndividual