Skip to main contentBiographyPainter Edward Hicks (1780–1849) is an icon of American folk culture and Quaker ideology. His work is easily identifiable through its simple forms and vivid palette. Hicks’s canvases possess an innocence both in style and subject matter that could only be a byproduct of pre-Civil War America. His charming paintings appeal to a broad viewing public, and he has become a highly celebrated figure in American art.

Hicks was born in Attleborough, Pennsylvania. His mother died shortly after his birth, and his father, who had fallen into financial hardship, gave the infant to a Quaker family to be raised. As a young man Hicks was apprenticed to a Pennsylvania coach maker. During this period, he learned the skills of sign painting and carriage ornamentation through the use of popular stock images. This artisan background is apparent in Hicks’s paintings, which often incorporate text and have unassimilated compositions.

In 1801 Hicks began his own business as a coach and sign painter, but abandoned his shop when his strong Quaker beliefs drew him to the ministry. In 1812, Hicks became a Quaker preacher. During the early period of his ministry, Hicks resisted his urge to paint because Quaker ideologies viewed art as a frivolity. He tried but failed to support his family through farming, so he turned back to the craft he had learned as a boy. Hicks remained conflicted about his art and religion but in 1817 began to paint more seriously. He found ways to reconcile this internal struggle by identifying himself as a craftsman, not an artist, and using his images as didactic tools that celebrated Quaker doctrine. At the age of seventy, Hicks wrote in his memoir, “I should be a burthen[sic] on my family and friends were it not for my knowledge of painting, by which I am still enabled to minister.” [1] This passage reveals the importance of his work as a spiritual tool.

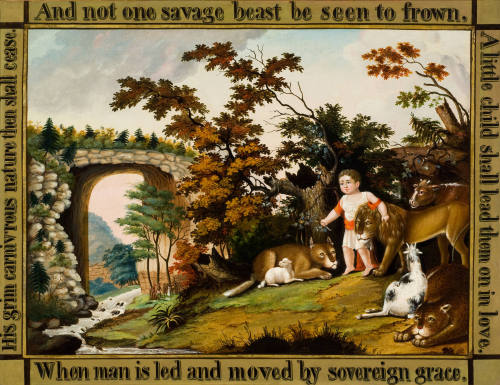

Hicks’s canvases sometimes portray American historic events such as Washington crossing the Delaware, but more often are informed by biblical text. The subject that dominates Hicks’s oeuvre is the peaceable kingdom; he is known to have painted sixty-two versions. The theme is drawn from the prophesy of Isaiah 11:6 and imagines a paradise in which the beasts of the world reside in peaceful unity with each other and mankind. The paintings always include a young child or children engaged with a menagerie of animals in an American landscape. This optimistic vision of God’s creatures coexisting in harmony is sweetened by Hicks’s simple, child-like rendering of figures, some of which can be identified as stock images used by American designers of the early nineteenth century. [2]

During his lifetime, Hicks’s imaginative canvases were overshadowed by the work of his more prominent contemporaries, such as Thomas Cole and William Sidney Mount. Hicks scholar David Tatham explains, “The peculiarities of his style (for it was not only masterly but also unconventional), the limited view he took of the function of the arts in society, and the self-effacing terms in which he spoke of himself as an artist all combined to exclude him from the art world of his day.” [3] Hicks’s conscious evasion of the American art establishment persisted throughout his lifetime.

It was long after his death that Hicks’s primitive style finally found acclaim. Early modernist collectors in New York embraced his work for its primitive purity; he was launched into the American consciousness by the 1932 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750–1900. Since the success of that show, Hicks has been considered more seriously by art historians. He is no longer lauded simply for his naiveté, but appreciated for the ingenuity of his work, which reveals both the cultural climate of early nineteenth-century America and the artist’s conservative Quaker ideologies.

Notes:

[1] Hicks, Memoirs of the Life and Religious Labors of Edward Hicks, Late of Newtown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA: Merrihew & Thompson Printers, 1851), 12.

[2] Carolyn J. Weekly and Laura Pass Barry, The Kingdoms of Edward Hicks (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1999), 90.

[3] David Tatham, “Edward Hicks, Elias Hicks and John Comly: Perspectives on the Peaceable Kingdom,” in American Art Journal 13, no. 2 (Spring 1981), 37.

Edward Hicks

1780 - 1849

Hicks was born in Attleborough, Pennsylvania. His mother died shortly after his birth, and his father, who had fallen into financial hardship, gave the infant to a Quaker family to be raised. As a young man Hicks was apprenticed to a Pennsylvania coach maker. During this period, he learned the skills of sign painting and carriage ornamentation through the use of popular stock images. This artisan background is apparent in Hicks’s paintings, which often incorporate text and have unassimilated compositions.

In 1801 Hicks began his own business as a coach and sign painter, but abandoned his shop when his strong Quaker beliefs drew him to the ministry. In 1812, Hicks became a Quaker preacher. During the early period of his ministry, Hicks resisted his urge to paint because Quaker ideologies viewed art as a frivolity. He tried but failed to support his family through farming, so he turned back to the craft he had learned as a boy. Hicks remained conflicted about his art and religion but in 1817 began to paint more seriously. He found ways to reconcile this internal struggle by identifying himself as a craftsman, not an artist, and using his images as didactic tools that celebrated Quaker doctrine. At the age of seventy, Hicks wrote in his memoir, “I should be a burthen[sic] on my family and friends were it not for my knowledge of painting, by which I am still enabled to minister.” [1] This passage reveals the importance of his work as a spiritual tool.

Hicks’s canvases sometimes portray American historic events such as Washington crossing the Delaware, but more often are informed by biblical text. The subject that dominates Hicks’s oeuvre is the peaceable kingdom; he is known to have painted sixty-two versions. The theme is drawn from the prophesy of Isaiah 11:6 and imagines a paradise in which the beasts of the world reside in peaceful unity with each other and mankind. The paintings always include a young child or children engaged with a menagerie of animals in an American landscape. This optimistic vision of God’s creatures coexisting in harmony is sweetened by Hicks’s simple, child-like rendering of figures, some of which can be identified as stock images used by American designers of the early nineteenth century. [2]

During his lifetime, Hicks’s imaginative canvases were overshadowed by the work of his more prominent contemporaries, such as Thomas Cole and William Sidney Mount. Hicks scholar David Tatham explains, “The peculiarities of his style (for it was not only masterly but also unconventional), the limited view he took of the function of the arts in society, and the self-effacing terms in which he spoke of himself as an artist all combined to exclude him from the art world of his day.” [3] Hicks’s conscious evasion of the American art establishment persisted throughout his lifetime.

It was long after his death that Hicks’s primitive style finally found acclaim. Early modernist collectors in New York embraced his work for its primitive purity; he was launched into the American consciousness by the 1932 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750–1900. Since the success of that show, Hicks has been considered more seriously by art historians. He is no longer lauded simply for his naiveté, but appreciated for the ingenuity of his work, which reveals both the cultural climate of early nineteenth-century America and the artist’s conservative Quaker ideologies.

Notes:

[1] Hicks, Memoirs of the Life and Religious Labors of Edward Hicks, Late of Newtown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA: Merrihew & Thompson Printers, 1851), 12.

[2] Carolyn J. Weekly and Laura Pass Barry, The Kingdoms of Edward Hicks (Williamsburg, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1999), 90.

[3] David Tatham, “Edward Hicks, Elias Hicks and John Comly: Perspectives on the Peaceable Kingdom,” in American Art Journal 13, no. 2 (Spring 1981), 37.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms