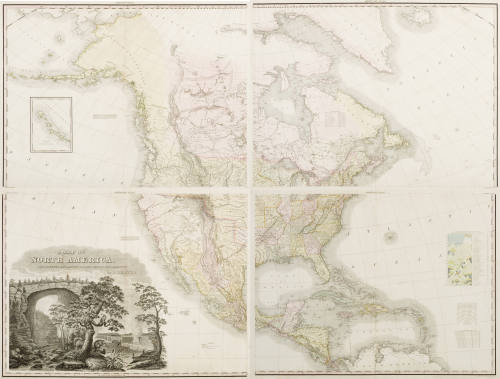

Skip to main contentBiographyThe opening decades of the nineteenth century are often called the “Golden Age of American Map Publishing” and reflect a thirst for knowledge about the New World on both sides of the Atlantic. Henry Schenk Tanner (1786–1858) was a dedicated cartographer who sought to fulfill that craving for information.

Tanner was born in New York City but lived most of his life in Philadelphia, the center of engraving and publishing at that time. He began his career working with John Melish, a Scotsman who had turned to map making and travel writing after a cotton import-export venture based in Glasgow and Savannah failed. Following Melish’s death in 1822, Tanner stepped in, creating maps of individual states, regions, and the entire country. In 1829 he produced, with assistance, his sixty-section, United States of America measuring fifty by sixty-four inches. Recognizing American mobility, in 1846 Tanner published The Traveller’s Guide or Map of the Roads, Canals and Rail Roads of the United States, a pocket map that a traveler might use en route. Branching beyond maps, in 1832 he issued A Geographical and Statistical Account of the Epidemic Cholera from its Commencement in India to its Entrance into the United States, which provided global, national, and local maps, as well as data tables showing the number of deaths in different localities by country. He was motivated to undertake this opus because he felt previous studies had been “given in such a loose and unconnected manner as to render a reference to them at once irksome and unprofitable.” [1]

More than just a mere mapmaker, Tanner was concerned about the design of his maps. In addition to statistical information he also included charming vignettes to fill in blank spaces. In an 1825 map of New England he devised a rocky island in a stormy sea, which conveniently bears the map’s title and his name. A small figure of a man with a telescope —perhaps a reference to himself—stands on top of the rocks and surveys a mountainous coastline. A tall-masted ship and a sailboat in distress add a narrative about the dangers of seafaring and allude to the importance of shipping to New England. Tanner’s various endeavors point to the significance of cartography for advancing trade on both land and sea and served to shape the boundaries of the country he so earnestly depicted.

Notes:

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Schenck_Tanner

Henry Tanner

1786 - 1858

Tanner was born in New York City but lived most of his life in Philadelphia, the center of engraving and publishing at that time. He began his career working with John Melish, a Scotsman who had turned to map making and travel writing after a cotton import-export venture based in Glasgow and Savannah failed. Following Melish’s death in 1822, Tanner stepped in, creating maps of individual states, regions, and the entire country. In 1829 he produced, with assistance, his sixty-section, United States of America measuring fifty by sixty-four inches. Recognizing American mobility, in 1846 Tanner published The Traveller’s Guide or Map of the Roads, Canals and Rail Roads of the United States, a pocket map that a traveler might use en route. Branching beyond maps, in 1832 he issued A Geographical and Statistical Account of the Epidemic Cholera from its Commencement in India to its Entrance into the United States, which provided global, national, and local maps, as well as data tables showing the number of deaths in different localities by country. He was motivated to undertake this opus because he felt previous studies had been “given in such a loose and unconnected manner as to render a reference to them at once irksome and unprofitable.” [1]

More than just a mere mapmaker, Tanner was concerned about the design of his maps. In addition to statistical information he also included charming vignettes to fill in blank spaces. In an 1825 map of New England he devised a rocky island in a stormy sea, which conveniently bears the map’s title and his name. A small figure of a man with a telescope —perhaps a reference to himself—stands on top of the rocks and surveys a mountainous coastline. A tall-masted ship and a sailboat in distress add a narrative about the dangers of seafaring and allude to the importance of shipping to New England. Tanner’s various endeavors point to the significance of cartography for advancing trade on both land and sea and served to shape the boundaries of the country he so earnestly depicted.

Notes:

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Schenck_Tanner

Person TypeIndividual