Skip to main contentBiographyMapping the human face is what portraitists do; they observe their subjects closely and use signature details to capture a likeness. This is the mode in which the artist Chuck Close (born 1940) works. At a time when realism was out of favor, Close emerged as one of the most highly regarded artists of the late twentieth century. Since 1967, Close’s subject matter has been limited to multiple variations of tightly cropped photographic headshots of family and art-world friends. Close’s artistic accomplishment is even more remarkable when one considers both his limited subject matter and his disabilities, both learning and physical. He suffers from prosopagnosia—face blindness—and is a quadriplegic. “He believes it [face blindness] has played a crucial role in driving his unique artistic vision. ‘I don’t know who anyone is and essentially have no memory at all for people in real space,’ he says. ‘But when I flatten them out in a photograph I can commit that to memory.’” [1] Since 1988, he has been confined to a wheelchair as a result of the “event” as he calls it—a collapsed spinal artery that left him paralyzed from the neck down.

Charles Thomas Close was born in Monroe, Washington, where his inventive father held a number of different handyman jobs, such as plumber and sheet metal worker, despite suffering from numerous health problems. The artist’s mother, Mildred Wagner Close, had trained as a classical pianist and gave music lessons. Despite their modest circumstances, both parents nurtured their son’s creativity and encouraged his interest in art. On his fifth birthday, Chuck Close got a paint set from the Sears catalogue, and, when he was eight, his neighbor gave him art lessons, including drawing from live models whom Close, in retrospect, suspects may have been prostitutes. His parents also helped their son perform magic acts and put on puppet shows for his peers, since a physical affliction made it impossible for him to run and play with them. His father died of a stroke when Close was eleven; that same year, his mother suffered from breast cancer and Close himself was confined to bed for many months with nephritis. Art became his escape and refuge. He remembered a painting by Jackson Pollock, which he had seen at the Seattle Art Museum; he had disliked it intensely but could not forget it, so he began to experiment with painting. His eighth-grade teacher strongly discouraged Close from pursuing college preparation courses in high school, mistaking his profound dyslexia for low academic potential. Nevertheless, Close attended Everett Community College, which had a strong art department, and then transferred to the University of Washington.

At the time, Close was painting in an Abstract Expressionist style, as well as creating work that was more political. He even cut up and reassembled an American flag, which caused an outcry from an American Legion Post. He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree magna cum laude from the University of Washington in 1962, having attended Yale University Summer School of Art and Music the summer before his senior year. He returned to Yale where he earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts with honors in 1963, and his Master of Fine Arts the following year. In New Haven, he joined an impressive group of graduate students, which included Nancy Graves, Richard Serra, Janet Fish, Brice Marden, and Robert Mangold. Upon graduation, Close, on a Fulbright scholarship, travelled with Graves and Serra to Europe, where he studied at the Akademie der Bildenden Kunste in Vienna. Returning to the United States, he taught for two years, 1965 through 1967, at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst before moving to New York City where he held a part-time position at the School of Visual Arts until 1971.

By 1966, he had developed his signature style, which involved taking photographs, drawing a grid on the print, and recreating the image greatly enlarged on a big canvas. Critical recognition came early to Close with his large-scale, black and white, airbrushed Big Self-Portrait of 1967–1968, purchased from the artist by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. This canvas was the first of his Photorealist series of eight “heads” of several friends who also would become famous, most notably Philip Glass and Richard Serra. Phil was purchased by the Whitney Museum of American Art in December 1969. In 1988, the Museum of Modern Art mounted a major retrospective. Close’s work is represented in major museum collections around the world.

In speaking of his decades of commitment to his chosen subject, Close said: “I’m surprised that I’m still painting heads after all these years. If somebody had told me thirty years ago that I would still be painting heads, I would have laughed hysterically. … What I wanted to do was alter my experience in the studio by changing the materials, changing the tools, changing the scale, changing the scale of the increment, using my body as a tool in the form of fingerprints, or spraying little stupid marks, or whatever the hell it was. And as each one of these things ran its course in terms of my own boredom and ease, then I would sort of naturally gravitate toward something else by altering other variables. I don’t mind being bored on one level … I try to make things that I think are important or valuable, and I am perfectly willing to put the time into them.” [2]

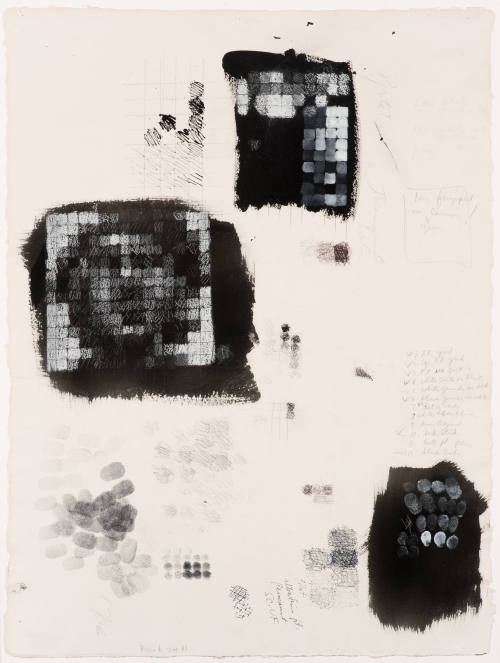

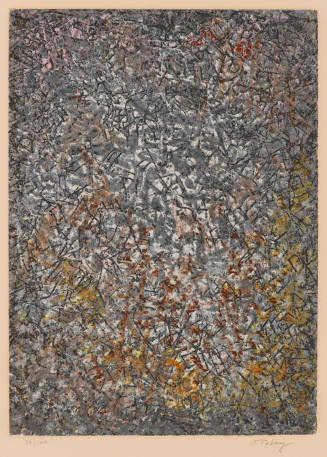

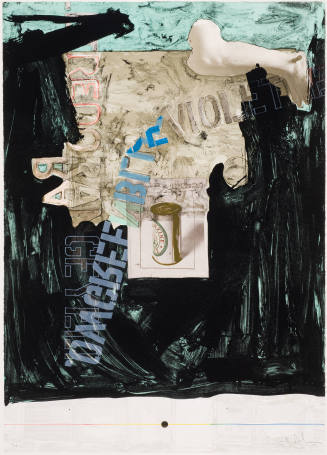

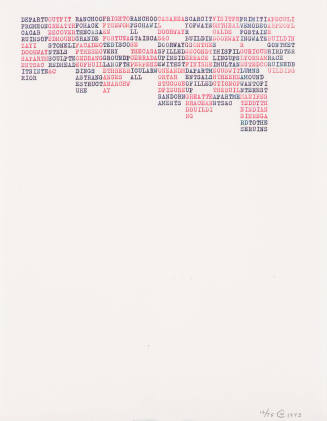

Close spent much of the seventies and eighties experimenting with different media, including various print processes, which he had first studied with renowned printmaker Gabor Peterdi at Yale, and which led in 1972 to working with master printmaker Kathan Brown at Crown Point Press to produce Keith/Mezzotint. This print was notable for its use of a historic and challenging technique, and was the first of Close’s works to leave visible the grid format that he has employed ever since. The artist continued with editions in other print media such as intaglio, silkscreen, linoleum, woodcut, and paper pulp. Between 1978 and 1985, Close made paintings and drawings using watercolor, pastel, ink, conté crayons, and even fingerprints. He has also explored various photographic processes; for example, during the 1980s he worked with large-format Polaroid cameras, first the 20-by-24 inch, then the 40-by-80 inch, and later, in the 1990s, with the nineteenth-century method of daguerreotype.

In spite of his disabilities, Close has accomplished a great deal; while he was still in the hospital undergoing rehabilitation, he managed with the greatest difficulty to paint a small head of artist Alex Katz. Over the years and with extensive physical therapy, he has regained partial use of his arms. Brushes are strapped to his hands and he moves his arms in order to paint, one grid square at a time. “All my work has been incremental from the very start. The various units were necessary for me to be able to isolate certain things to be dealt with. No matter how I’ve worked I’ve always pretty much finished an area before I’ve moved on. Make the decisions, try to figure out how to say it, do it.” In looking at the direction his work was taking in the late 1980s, his subsequent stylistic evolution since his paralysis seems to follow a natural continuum with his earlier work. It is very important to Close that his art be judged on its own merits and, as he says, “I don’t want to be a handicapped artist. I happen to be an artist with a handicap, and it informs the work, but I don’t want to be the poster boy for quadriplegia.” [3]

In his later years, Close accepted a few photographic commissions of people who interested him—former president Bill Clinton and the actor Brad Pitt, for example—that diverge from his other work. Like the work of Andy Warhol, Close’s artwork is simultaneously recognizable because of its distinctive style and its portrait subject matter. But the difference between Warhol and Close is that for the former his subjects were celebrities or socially elite, whereas for Close his typical subjects are friends or family, even if some are or become famous. As portraits go, neither Close nor Warhol concerns himself with revealing the sitter’s individuality. Like his friend Alex Katz, Close chooses to depict members of his family and art world friends, but unlike Katz his actual subject is the photograph he takes and how he translates it to a different scale in other media.

Looking back and analyzing his work, Close once declared “everything that I’ve finished, I feel or I felt good about when I finished it. I don’t always feel that way six months or a year or several years later, but at least at the time that I finished it I do. I guess it’s something about craft. It’s a way somebody constructs a book or a poem or whatever it is, there is a certain level of finish, a certain consistency. I wanted to be consistent. I wanted to feel like the same voice throughout, the same attitude throughout. The same guy finished the painting that started it.” [4]

Notes:

[1] Oliver Sacks, “Face-Blind: Why are some of us terrible at recognizing faces?” in The New Yorker, August 30, 2010, 39.

[2] Robert Storr, Chuck Close. Exhibition catalogue. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 92–93.

[3] Chuck Close, interview with Jud Tully, May 14–September 30, 1987, New York. Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-chuck-close-13141 and Joanne Kesten, ed., The Portraits Speak: Chuck Close in conversation with 27 of his subjects (New York: Art Resources Transfer Press, 1997), 366.

[4] Storr, Chuck Close, 100.

Chuck Close

American, 1940 - 2021

Charles Thomas Close was born in Monroe, Washington, where his inventive father held a number of different handyman jobs, such as plumber and sheet metal worker, despite suffering from numerous health problems. The artist’s mother, Mildred Wagner Close, had trained as a classical pianist and gave music lessons. Despite their modest circumstances, both parents nurtured their son’s creativity and encouraged his interest in art. On his fifth birthday, Chuck Close got a paint set from the Sears catalogue, and, when he was eight, his neighbor gave him art lessons, including drawing from live models whom Close, in retrospect, suspects may have been prostitutes. His parents also helped their son perform magic acts and put on puppet shows for his peers, since a physical affliction made it impossible for him to run and play with them. His father died of a stroke when Close was eleven; that same year, his mother suffered from breast cancer and Close himself was confined to bed for many months with nephritis. Art became his escape and refuge. He remembered a painting by Jackson Pollock, which he had seen at the Seattle Art Museum; he had disliked it intensely but could not forget it, so he began to experiment with painting. His eighth-grade teacher strongly discouraged Close from pursuing college preparation courses in high school, mistaking his profound dyslexia for low academic potential. Nevertheless, Close attended Everett Community College, which had a strong art department, and then transferred to the University of Washington.

At the time, Close was painting in an Abstract Expressionist style, as well as creating work that was more political. He even cut up and reassembled an American flag, which caused an outcry from an American Legion Post. He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree magna cum laude from the University of Washington in 1962, having attended Yale University Summer School of Art and Music the summer before his senior year. He returned to Yale where he earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts with honors in 1963, and his Master of Fine Arts the following year. In New Haven, he joined an impressive group of graduate students, which included Nancy Graves, Richard Serra, Janet Fish, Brice Marden, and Robert Mangold. Upon graduation, Close, on a Fulbright scholarship, travelled with Graves and Serra to Europe, where he studied at the Akademie der Bildenden Kunste in Vienna. Returning to the United States, he taught for two years, 1965 through 1967, at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst before moving to New York City where he held a part-time position at the School of Visual Arts until 1971.

By 1966, he had developed his signature style, which involved taking photographs, drawing a grid on the print, and recreating the image greatly enlarged on a big canvas. Critical recognition came early to Close with his large-scale, black and white, airbrushed Big Self-Portrait of 1967–1968, purchased from the artist by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. This canvas was the first of his Photorealist series of eight “heads” of several friends who also would become famous, most notably Philip Glass and Richard Serra. Phil was purchased by the Whitney Museum of American Art in December 1969. In 1988, the Museum of Modern Art mounted a major retrospective. Close’s work is represented in major museum collections around the world.

In speaking of his decades of commitment to his chosen subject, Close said: “I’m surprised that I’m still painting heads after all these years. If somebody had told me thirty years ago that I would still be painting heads, I would have laughed hysterically. … What I wanted to do was alter my experience in the studio by changing the materials, changing the tools, changing the scale, changing the scale of the increment, using my body as a tool in the form of fingerprints, or spraying little stupid marks, or whatever the hell it was. And as each one of these things ran its course in terms of my own boredom and ease, then I would sort of naturally gravitate toward something else by altering other variables. I don’t mind being bored on one level … I try to make things that I think are important or valuable, and I am perfectly willing to put the time into them.” [2]

Close spent much of the seventies and eighties experimenting with different media, including various print processes, which he had first studied with renowned printmaker Gabor Peterdi at Yale, and which led in 1972 to working with master printmaker Kathan Brown at Crown Point Press to produce Keith/Mezzotint. This print was notable for its use of a historic and challenging technique, and was the first of Close’s works to leave visible the grid format that he has employed ever since. The artist continued with editions in other print media such as intaglio, silkscreen, linoleum, woodcut, and paper pulp. Between 1978 and 1985, Close made paintings and drawings using watercolor, pastel, ink, conté crayons, and even fingerprints. He has also explored various photographic processes; for example, during the 1980s he worked with large-format Polaroid cameras, first the 20-by-24 inch, then the 40-by-80 inch, and later, in the 1990s, with the nineteenth-century method of daguerreotype.

In spite of his disabilities, Close has accomplished a great deal; while he was still in the hospital undergoing rehabilitation, he managed with the greatest difficulty to paint a small head of artist Alex Katz. Over the years and with extensive physical therapy, he has regained partial use of his arms. Brushes are strapped to his hands and he moves his arms in order to paint, one grid square at a time. “All my work has been incremental from the very start. The various units were necessary for me to be able to isolate certain things to be dealt with. No matter how I’ve worked I’ve always pretty much finished an area before I’ve moved on. Make the decisions, try to figure out how to say it, do it.” In looking at the direction his work was taking in the late 1980s, his subsequent stylistic evolution since his paralysis seems to follow a natural continuum with his earlier work. It is very important to Close that his art be judged on its own merits and, as he says, “I don’t want to be a handicapped artist. I happen to be an artist with a handicap, and it informs the work, but I don’t want to be the poster boy for quadriplegia.” [3]

In his later years, Close accepted a few photographic commissions of people who interested him—former president Bill Clinton and the actor Brad Pitt, for example—that diverge from his other work. Like the work of Andy Warhol, Close’s artwork is simultaneously recognizable because of its distinctive style and its portrait subject matter. But the difference between Warhol and Close is that for the former his subjects were celebrities or socially elite, whereas for Close his typical subjects are friends or family, even if some are or become famous. As portraits go, neither Close nor Warhol concerns himself with revealing the sitter’s individuality. Like his friend Alex Katz, Close chooses to depict members of his family and art world friends, but unlike Katz his actual subject is the photograph he takes and how he translates it to a different scale in other media.

Looking back and analyzing his work, Close once declared “everything that I’ve finished, I feel or I felt good about when I finished it. I don’t always feel that way six months or a year or several years later, but at least at the time that I finished it I do. I guess it’s something about craft. It’s a way somebody constructs a book or a poem or whatever it is, there is a certain level of finish, a certain consistency. I wanted to be consistent. I wanted to feel like the same voice throughout, the same attitude throughout. The same guy finished the painting that started it.” [4]

Notes:

[1] Oliver Sacks, “Face-Blind: Why are some of us terrible at recognizing faces?” in The New Yorker, August 30, 2010, 39.

[2] Robert Storr, Chuck Close. Exhibition catalogue. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 92–93.

[3] Chuck Close, interview with Jud Tully, May 14–September 30, 1987, New York. Archives of American Art, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-chuck-close-13141 and Joanne Kesten, ed., The Portraits Speak: Chuck Close in conversation with 27 of his subjects (New York: Art Resources Transfer Press, 1997), 366.

[4] Storr, Chuck Close, 100.

Person TypeIndividual